Series Table of Contents:

Introduction (what sacred/liturgical time is and why we have it)

⇒ The Canonical Hours (the Catholic “clock”)

The Former Holy Week (pagan antecedents of the week)

The Seventh Day (the Judaic week and the Sabbath)

The Revelation of the Octave (the Catholic week)

To Everything There Is a Season (Easter computus; fourfold interpretation of Scripture)

The Waxing of the Sun (the literal/meteorological year; the yearly allegory of the life of Christ)

The Waning of the Sun (the spiritual life through the lens of the year)

A Time to Get, and a Time to Keep (liturgical seasons in the Anglican Use)

Sunset to Sunset

In our exploration of sacred time, a natural place to begin is with the individual day. Since the second or third century, Christians have observed set times of prayer every day, known as the canonical1 hours or the divine office. In most rites, African, Asian, or European,2 there are normally seven or eight hours, or occasionally three. In the eightfold schema, they traditionally map—rather inexactly—onto our clock like this:

The colors aren’t from anywhere

—I just thought they looked nice

If that image isn’t legible, the salient times are:

2 a.m.: Matins (now called the Office of Readings in standard usage)

5 a.m.: Lauds (the idea is for it to run from dawn3 to actual sunrise)

7 a.m.: Prime

9 a.m.: Tierce (or Terce)

12 noon: Sext

3 p.m.: Nones

6 p.m.: Vespers (as with Lauds, conceptually meant to run from sunset to dusk proper3)

8 p.m.: Compline4

Great! What on earth are those all on about? To understand them and their associations, let’s just quickly rewind about nineteen to twenty-eight centuries.

Worship in the Ancient World

In templar Judaism—and indeed, in most ancient religious practice—the most basic act of worship was the קָרְבָּן [qârbân] (קָרְבָּנוֹת [qârbânoth]5 in the plural); the radical קרב [q-r-b] encodes meanings like “near” and “approach,” so this becomes the linguistic root of קָרְבָּן, meaning “sacrifice.” The English sacrifice, derived from Latin, has a different history behind it; a sacrificium was “a thing made holy”: sacer “holy” + facere “to make, do.” An image of handing something over can be discerned in both words, perhaps seen from opposite perspectives. The key thing here is, for most of human civilization, worship and offering sacrifice were simply synonymous activities.

In any case, while the Temple stood, a great variety of קָרְבָּנוֹת were offered at various times. Most of them were brought for some personal or national occasion: the birth of a child, atoning for a broken vow, etc. But no matter what else was offered, every day, a lamb was sacrificed to God first thing in the morning, and a lamb was sacrificed around mid-afternoon. These two sacrifices were called the תָמִיד [tâmydh], which can be interpreted “daily” or “always.”

A high priest offering incense on the altar

of incense within the Sanctuary.

Illustration from Henry Davenport

Northrop’s 1894 Treasures of the Bible.

Still, most Jews back then did not live close enough to the Temple to go there every day, or even every sabbath. Moreover, from early on in the history of Judaism, prophets were already emphasizing that “to obey is better than sacrifice, and to hearken than the fat of rams” (I Sam. 15:22). The date of Psalm 50 (like that of many psalms) is not known, but its imagery is shared by “Proto-Isaiah”6 and Micah, so it may express theology that already existed in the pre-Exilic period: its vv. 7-15 say,

Hear, O my people, and I will speak;

…O Israel, and I will testify against thee:

I am God,

…even thy God.

I will not reprove thee for thy sacrifices

…or thy burnt offerings, to have been continually before me.

I will take no bullock out of thy house,

…nor he goats out of thy folds.

For every beast of the forest is mine,

…and the cattle upon a thousand hills.

I know all the fowls of the mountains:

…and the wild beasts of the field are mine.

If I were hungry, I would not tell thee:

…for the world is mine, and the fulness thereof.

Will I eat the flesh of bulls,

…or drink the blood of goats?

Offer unto God thanksgiving;

…and pay thy vows unto the most High:

And call upon me in the day of trouble:

…I will deliver thee, and thou shalt glorify me.

A Sacrifice of Praise

In consequence (as it seems), to participate in worship (a) spiritually and (b) especially when remote from the Temple, the custom of daily prayer developed, employing psalms and prayers and readings just like Temple services. Corresponding to the tamydh, two hours of prayer developed, one at sunrise (שַחֲרִית [Shacharyth]) and one in mid-afternoon (מִנחַה [Minchah], alluded to in Acts 3:1). A third hour developed too, מַעֲרִיב [Ma3aryv], or prayer before bed; no sacrifices were offered after sunset, but the “unfinished” remains of earlier offerings were burnt.

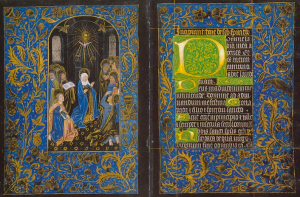

A two-page spread from the Morgan Black Hours,

a luxury Book of Hours created in Flanders

during the Renaissance.

These are likely the prayers that the infant Church in Jerusalem devoted itself to alongside “the apostles’ doctrine and fellowship and breaking of bread.” Other traditions, like standing being the default posture for Christian prayer,7 may also owe something to the customs of Judaic prayer.

Among Christians, the hours of Lauds and Vespers became the most important.8 The former was associated with the Resurrection, and perhaps owed something to Shacharyth; the latter came to be associated with the Last Supper, and may have drawn on Minchah, albeit pushed to the end of the day—for the Christian clock had gone on ticking.

Note: The next two sections, “The Hours of the Passion” and “Vigils,” are both primarily of historical interest. If you’re only interested in the practical point of the canonical hours, you might prefer to skip to the section “The Enemy.”

The Hours of the Passion

An ikon of the Crucifixion, late 13th or early

14th c., by Duccio di Buoninsegna.

The canonical hours were changed from three to seven under the ostensible influence of Psalm 119:164; an eighth was later added as well. We have addressed Lauds and Vespers; thirdly, Compline perhaps owed something to Ma3aryv. That leaves us with five further hours to discuss: Matins, Prime, Tierce, Sext, and Nones.

Tierce, Sext, and Nones seem to have been introduced and promoted together. The Apostolic Tradition, possibly the work of St. Hippolytus of Rome (who died in the early third century), treats them as key hours in the progress of the Passion. The Gospel of John represents them as the hours of Jesus’ sentencing by Pilate, the actual Crucifixion, and Jesus’ death; the Synoptics put the Crucifixion at Tierce, but make the darkening of the sky over the Holy Land begin at noon. Tierce has the additional association of being the hour the Holy Ghost descended at Pentecost.

The aforementioned eighth hour was Prime. Now, eight is one beyond seven, which symbolizes the week and thus the normal passage of time; therefore, eight represents eternity and the Resurrection—Christ is described as rising “on the eighth day [of the week],” and baptisteries and fonts are frequently octagonal. However, Prime was not devised to remind us of eternity; it has a much funnier backstory. Prime was originally instituted to prevent monks from going back to bed till Tierce after saying Lauds. (Admittedly, this doesn’t make great fodder for meditation, so it has also been associated with Jesus being presented to Pilate.) Prime was suppressed after Vatican II, at least to the extent of being made a non-standard option instead of a normal part of the Office.

A bell from the Church of SS. Alexander Nevsky

and Nicholas in Tampere, Finland; church bells

often mark either the twenty-four hours of the

civil clock or the canonical hours of prayer.

Vigils

Finally, Matins, a.k.a. the Office of Readings—which isn’t its first name change: Its original name in Latin was vigiliæ, Vigils. The trad-ly inclined might assume the reason the Office of Readings may now be said at any time of the day rather than only midnight, is one more instance of post-Vatican II laxity, but this is not the case. The old timing of Matins appears to reflect an aspect of human biology that the industrial and technological ages have rendered obscure. Now, I am personally confident in the following, as the evidence for it seems good and it fits in rather well with other facts; however, it is not universally accepted, and in any case, my degree isn’t in medicine or even biology.

Historical research by A. Roger Ekirch, a professor at Virginia Tech, seems to indicate that in pre-industrial societies, it was normal to practice what’s called biphasal sleep. Basically, you go to sleep not long after nightfall, for three or four hours—this was “first sleep.” Then, close to midnight, you wake up for an hour or so; maybe you spend the time quietly thinking, or … with your spouse,9 or stargazing, or doing crimes. Then, you go back to bed for “second sleep,” which lasted another few hours until close to sunup. From as far back as the Apostolic Tradition, the office of Vigils was designated for prayer in the middle of the night; this is why Matins is associated, on paper, with two in the morning.

A twenty-four hour clock face from the Duomo

in Florence. (Note that the hours are arranged

in an order we regard as anti-clockwise.)

Nowadays, it’s understood that we need adequate sleep for our physical and mental health, and we all stay up worrying about it. This was not well-recognized in antiquity or the Middle Ages, however, and the Desert Fathers, who formed the root of monasticism, kind of hated sleep for some reason—perhaps they regarded it as a triumph of our irrational nature. Even after their severity was tempered by the gentleness of St. Benedict, it looks as if the usual monastic custom was to just skip second sleep and treat the second part of the night as a time to study by lamplight (especially for novices, who were still learning things like how to intone the Psalms). This is how Matins came to be the Office of Readings in the first place, an office with more and longer readings from Scripture than the others, as well as selections from the writings of the saints and fathers.

Today—ironically, given which age has electric lighting and which didn’t—studies are mostly conducted during the day. Whether it would be better for us or not, it isn’t usual any more to rise at midnight, except to heed nature’s call or get in line for a new iPhone. It really doesn’t make sense to get up in the middle of the night for the express purpose of saying the Office of Readings if you’re used to mono-phase sleep; that just sounds like a way to learn little or nothing from the readings in question, if you even succeed in staying awake all the way through them.

A crescent moon over Arizona. Photo by Beth

Woodrum, made available under

a CC BY-SA 2.0 license (source).

The Enemy

So … who cares?

I do think there is some value in maintaining traditions just because. Certainly, I draw the line at inconvenience and hard work; but that leaves a lot more intact than you might suppose, especially if you approach both old traditions and new realities with a little imagination. It’s the kind of thing that gives us a sense of continuity with those who have gone before us. However, while pleasant, this is merely pleasant. There’s nothing wrong with it as a motive, but it doesn’t make the hours tools in your spiritual arsenal.

They are, though. At least, they can be. The thing the hours fight, partly by the steady diet of Scripture they feed us with but most just by recurring, is—well, it seems convenient to give it the old-fashioned name of “the noonday demon”: It is also called ἀκηδία [akēdia] or accidie,10 a condition that is sometimes confused with sloth but is really quite different from it. Sloth is a disproportionate love of rest and familiarity. Accidie isn’t a love at all; it is a repugnance. It is a joyless, restless, listless distaste for everything and especially for divine things, apt to attack without warning. It is irrational, which can make it strangely immune to the appeals of reason. Accidie, I suspect, douses far more candles of faith than intimidation ever could.

But the simple, steady trudge of the canonical hours, in their daily and day-by-day rhythm, gives us a weapon against accidie. They are arbitrary enough to meet it on its own ground (since all measurement of time is conventional), but still rational enough that you won’t feel stupid using them.

Tolle, lege; tolle, lege.

A page from the Aberdeen Breviary, an early

16th c. book of hours, showing the beginning

of Matins on a Sunday.

Footnotes

1This word comes from the same source as the “canon” of Scripture: Greek κανών [kanōn], “measuring rod; standard, rule.”

2A rite is the name for a given Christian community’s total ritual practice: liturgies, sacraments, canons, and calendar. Most rites are celebrated by both Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches, with a few exceptions (e.g., the split in the Armenian Church is between the Rome-aligned Armenian Catholic Church and the Armenian Apostolic Church, an Oriental Orthodox Church). There are six basic ritual families, with a few important variants:

i) the Alexandrian family, whose “main” form is from Egypt (the Coptic Rite), with a major variant in Ethiopia (the Ethiopic Rite);

ii) the Antiochene (or West Syriac) family, with the Melkite Rite of Syria representing the “main” form and two major variants, one in Lebanon (Maronite) and the other in India (Syro-Malankara);

iii) the Armenian Rite (the only one-rite family);

iv) the Byzantine (or Greek) family, with more than a dozen national variants, mostly from Eastern Europe;

v) the East Syriac family (which has many alternate names, including Assyrian, Babylonian, and Persian), whose “main” form is native to Iraq (the Chaldean Rite), also with a variant in India (Syro-Malabar); and

vi) the Latin family, whose center of gravity is Rome (home of the Roman Rite), though there are a handful of other local rites, e.g. the Ambrosian Rite (used in Milan), or the Mozarabic (Toledo).

3If you haven’t run across this distinction before, dawn indicates the first appearance of daylight, which at temperate latitudes is typically an hour before the sun crests the horizon (tending to run longer as one approaches the Arctic or Antarctic Circles). Likewise, the sun normally sets about an hour before dusk, the last disappearance of daylight.

4These names are adaptations from Latin. Their meanings are as follows: Matins, “morning”; Lauds, “praises”; Prime, Tierce, Sext, and Nones, “first,” “third,” “sixth,” and “ninth” respectively; Vespers, “evening”; and Compline, “finished.”

5I use a system of Hebrew transliteration that aims for a “one Hebrew letter-one Roman letter” equivalence, including niqqud (vowel pointing) as letters. However, as in English, spelling does not always line up exactly with pronunciation; קָרְבָּן is more often transliterated korban. (The qamatz gadol—which roughly means “long a” and looks a bit like a subscript T—could indicate the a of “father” or more of an aw-sound).

6Isaiah is conventionally divided into three sub-books: First or Proto-Isaiah (the first 39 chapters), the earliest portion, dating to the eighth century BCE and substantially the work of Isaiah ben Amoz; Second or Deutero-Isaiah (chapters 40-55), written near the end of the Exile; and Third or Trito-Isaiah (chapters 56-66), composed after the return, in the late sixth and early fifth centuries. As to why these three discrete bodies of work were all compounded into the single book of Isaiah, there were “companies” or “households” of prophets in ancient Israel (cf. I Sam. 19:18-24, II Kings 6:1-3, Amos 7:12-15). Isaiah ben Amoz was, so to speak, a very successful prophet, active under four kings (Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah), and his prophecies could easily have attracted a large following, especially since three of these kings “did what was right in the eyes of the Lord.” This Isaian group might then have produced the authors of Deutero- and Trito-Isaiah. (The Carmelite Order claim to continue the “household” of Elijah and his successor Elisha.)

7Many people mistakenly assume that kneeling is the normative posture for Christian prayer. However, prayer while kneeling is specifically associated with either penitence or the adoration of a theophany (including the Eucharist). Standing is the proper posture for most formal, public prayer. As mentioned, this is likely inherited from Judaism: The Amidah, the central prayer said at Shacharyth, Minchah, and Ma3aryv, literally means “standing,” which is sometimes connected with Ezekiel 1:7, where the Cherubim or the Thrones (or both) are described as standing upright, and all their movements as proceeding in straight lines.

8Not that they were called this at the time. In the first generations of Christianity, Greek rather than Latin was the chief language of European believers; in Greek, Lauds and Vespers are Ὄρθρος [Orthros], “upright,” and Ἑσπερινός [Hesperinos], “evening.”

9Or indeed, with not your spouse.

10Pronounce this word as if it were spelled axidy, and you’ve got it.