Series Table of Contents:

Introduction (what sacred/liturgical time is and why we have it)

The Canonical Hours (the Catholic “clock”)

The Former Holy Week (pagan antecedents of the week)

The Seventh Day (the Judaic week and the Sabbath)

The Revelation of the Octave (the Catholic week)

⇒ To Everything There Is a Season (Easter computus; fourfold interpretation of Scripture)

The Waxing of the Sun (the literal/meteorological year; the yearly allegory of the life of Christ)

The Waning of the Sun (the spiritual life through the lens of the year)

A Time to Get, and a Time to Keep (liturgical seasons in the Anglican Use)

The Sacred Year

Alright. We have discussed the basic idea of sacred time; we have reviewed the daily cycle of the hours; and we have reviewed the origin of the week, the original significance of the Sabbath, and the significance of the new Sunday Sabbath and the Christian week as a whole. There is no basic structure of the “Christian month,”1 so the next step up is the annual cycle.

The Christian calendar differs from one place to another; for instance, in the Christian East (which here mainly means Eastern Europe, the Near East, and India), the liturgical year typically begins in September rather than December. However, to the best of my knowledge, there are three basic divisions of the year found in all Christian calendars2:

- The Christmas cycle;

- The Easter cycle; and

- Other.3

(The “other” part of the calendar is typically given some more specific character in individual calendars. However, it isn’t consistent from one tradition to the next the way Christmas and Easter are.)

Statistically, if you’re familiar with a Catholic calendar, it’s the General Roman Calendar (GRC). Countries and dioceses that celebrate the Roman Rite have national and diocesan variants of this, commemorating saints of special importance to them (whether or not they’re on the GRC), and sometimes ranking celebrations slightly differently, at the discretion of the bishops’ conference; however, the scaffold they’re built on is always the same.

Title page of Cranmer’s 1549 The booke of the

common prayer and administration of the Sac-

ramentes, and other rites and ceremonies of

the Churche: after the use of the Churche of England.

Here, I’m going to stick to the calendar I know best, which is the Ordinariate’s4 Anglican Use calendar. This is based on the Book of Common Prayer; that is in turn based largely on a few Medieval English forms of the Mass. It’s basically Roman both in structure and most details. However, the Anglican service didn’t undergo all the same reforms as the Roman Rite did (though there have been and still are trans-denominational influences). Hence, the Anglican Use calendar is a little more elaborate than the GRC, particularly its rich range of seasons and sub-seasons.

I said in my initial post in this series that there are five basic seasons in the liturgical year. They don’t cover everything, but they lay the groundwork for the rest. In the Anglican Use, they are:

- Advent

- Epiphanytide (yes, Epiphanytide; why is complicated, we’ll get to it)

- Lent

- Eastertide

- Trinitytide (mostly but not entirely equivalent to “Ordinary Time”5)

Note how they follow the structure of the life of Christ, especially if we treat Trinitytide as the period after the Ascension and Pentecost. (Remember: he is no longer visibly on earth, but Jesus is in the strict sense still alive, so this period does also qualify as part of “the life of Christ.” It’s not part of his earthly ministry, true—but then, neither was most of his visible life.)

The first, second, and fifth chunks of the year here are more or less fixed, but the third and fourth involve what are known as movable feasts. For that, we need to talk about …

Computus

The Hebrew calendar is lunisolar: its months are determined by the real waxing and waning of the Moon, and most years have twelve of them. But, because twelve lunar months fall a few days short of a solar year, a “leap month” is added a little more than a third of the time (according to a schedule called the Metonic cycle). The date of Jesus’ Passion was of course determined by this calendar.

Based mainly on the Roman civil calendar, the Catholic calendar is a solar calendar—mostly. Our “months” are more conceptual than real, in the sense that the Moon never takes as little as twenty-eight days or as many as thirty-one to pass through its entire phase cycle.6

That “mostly” is about the Paschal, or Easter, cycle. It is governed by a lunisolar calendar, as it always has been; this affects the exact timing of the liturgical seasons, the relative length of Epiphanytide and Trinitytide, and of course the actual dates on which we observe Ash Wednesday, the Triduum, Easter Sunday, Ascension, Pentecost, Corpus Christi, and the Sacred Heart. In the earliest period of Christian history, Easter was simply calculated by finding out from Jewish neighbors when Passover was. The calculation of its date (the computus paschalis, or just computus) has changed hands more than once since. For western Christians, the date is now set by the Vatican’s astronomers. The short version is that Easter is the Sunday after the full moon that occurs on or after 21 March: 22 March is the earliest possible date of Easter, and 25 April is the latest.

The Seasons (1897), a set of four lithographs

by Alphonse Mucha, a Czech painter and

illustrator associated with the art nouveau

movement.

The Fourfold Method

Because it is a model of the life of Christ, the liturgical year is also a model of redemptive history. This is a key example of where the old fourfold method of interpreting Scripture comes in handy for discerning meaning in things. These are not well-known today, so let’s go over them in brief. Their names are:

- Literal

- Allegorical (also called typological)

- Moral

- Mystical (or anagogical7)

Now. What do they mean?

i. Literal Interpretation

You would expect the literal sense to be the easiest, and in a way it is. However, in the US, “literal interpretation” has come to mean something a bit—well—wrong (thank you C. I. Scofield for ruining it for everyone). “Literal,” in the context of hermeneutics, does not indicate the flat-footedly literal meaning of a text; it indicates what the text means as a piece of literature, understood the way anybody reading it or listening to it at the time would have understood it. “Literary” might be a better word for this method than “literal.”

One of the ways this can get confusing is that some devices and even whole genres of literature are figurative. For example, for the parable of the sower in Matthew 13:3-9, the literal/literary meaning is the meaning Jesus explains privately to the disciples in vv. 18-23. The flat-footedly literal meaning is simply what the words say, but parables as a literary form rule out their own flat-footedly literal meanings, automatically: somebody who said that the parable of the sower was about a man actually going outside and throwing seeds into the dirt would be wrong about what the parable meant.

As I said, this throws some people (thank you John Nelson Darby and Charles Ryrie for also ruining it for everyone). However, while applying the principle can take some research, the idea is far easier to handle than it may seem. Really, it’s just an extension of the same principle that makes metaphors work. If someone tells you “I’m heartbroken,” do you scream “Oh my God, we need to get you to emergency cardiac surgery!” and start dialing for an ambulance? No—at least, while I don’t know you, I hope you don’t do that. You recognize it as a metaphor, even though they might, within mere minutes, also go on to say “My glasses are broken” and expect you to take it with flat-footed literalism. Sensitivity to the original genre, context, and language are necessary; in other words, you need to know what kind of literature you’re dealing with in order to extract the right literary meaning.

This level of meaning has to be established first. The next three modes of interpretation are how that literary meaning can apply in three further contexts, or from three additional perspectives.8

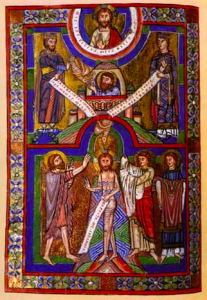

An illumination linking the Flood of Noah with

the baptism of Christ allegorically, along the`

lines of I Peter 3:20-21.

ii. Allegorical Interpretation

Allegory means something much more specific in this context than in did in high school English.9 It approaches Scriptural texts and stories, especially those of the Old Testament, as being in some sense about the person and work of Christ. Matthew and the Pauline letters are rich in allegorical interpretations, also referred to as typology (if you’ve heard the expression that such-and-such in the Old Testament is “a type of Christ,” this is where that comes from); Galatians 4 is a salient example.

iii. Moral Interpretation

The method of moral interpretation applies texts to the moral life. This was a favorite device for interpreting the ritual laws of the Torah in a way that was still relevant to the Church after their suspension.10

iv. Mystical Interpretation

14th-c. tapestry depicting the New Jerusalem—

photo by Octave 444, used under

a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

This level of interpretation refers the text in question to the soul’s final union with God. For instance, Jesus’ assurance that “I will not leave you comfortless: I will come to you” was literally addressed to the Eleven (Judas had left by then), apparently referring both to the Resurrection and to Pentecost. But it can also be applied in two mystical senses, one as a description of what takes place at death, and the other in reference to the Second Coming.

These are basically three “spirits” which all derive from the letter of the text. If you think of the allegorical sense as being about our faith, the moral sense about our love, and the mystical about our hope, that’s at least a good mnemonic.

That is probably plenty to be getting on with! We’ll apply these to the liturgical calendar more thoroughly next time.

Footnotes

1This is slightly different from the ritual laid down in the Torah. The first of each month in the Hebrew calendar is a minor holiday, רֹאשׁ חֹדֶשׁ [ro’sh chodhêsh], which means “head of the month.” Additionally—and, to my knowledge, purely by coincidence—there are a few date correspondences in several months in the Christian calendar. For instance, the solstices and equinoxes have festivals associated (imprecisely) with them, and so do most of the intervening months: Christmas (25 Dec.), Conversion of Paul (25 Jan.), Chair of Peter (22 Feb.), Annunciation (25 March), St. Mark (25 April), Nativity of the Baptist (24 June), St. James the Greater (25 July), St. Bartholomew (24 Aug.), St. Matthew (21 Sept.), and the Presentation of the Mother of God (21 Nov.).

2That is, all Christian calendars from the “apostolic” traditions: the Anglican, Armenian, Assyrian, Catholic, Ethiopic, Lutheran, and Orthodox. Most “low church” traditions retain traces of this system; the only ones I’ve heard of that scrap even Easter are the Quakers and Jehovah’s Witnesses (though the latter observe Good Friday).

3Interestingly, though this is surely happenstance, this aligns with the three seasons whose names can be traced all the way back to Proto-Indo-European: winter, spring, and summer.

4This is (now) the same thing as the Anglican Use. Long story short, we are formerly Anglican/Anglican-adjacent communities and individuals who have become Catholic: we are in full communion with the Pope, but our liturgy retains many distinctive elements preserved in the tradition of the Church of England.

5This was not intended to convey the idea that the season in question is “ordinary” in the sense of being normal and therefore humdrum. The name referred simply to the fact that this season is measured by its Sundays in numerical, or ordinal, sequence. Personally, I don’t feel that that’s a lot better? It certainly doesn’t give Ordinary Time any distinctive character; it seems to be just telling the laity “No no, don’t be bored!” Either way, though, why not call it “Ordinal Time,” which is literally the thing you’re ostensibly talking about? I don’t know who’s in charge of translating and adapting texts for Anglophone use in the Catholic Church, but when I catch him, he’ll get a hiding.

6The lunar cycle is in fact almost exactly 29.5 days. This is why, in strict lunisolar calendars, months regularly alternate between having twenty-nine days and thirty days.

7Annoyingly, it’s not unknown (especially in medieval sources) for all three non-literal interpretations to be called “allegorical” or “mystical,” since this just wasn’t complex enough. The terms typological and anagogical come from the Greek τύπος [tüpos], meaning “impression, mark, print,” and ἀναγωγή [anagōgē], meaning “leading up” or “lifting up.”

8This is partly why not every text is necessarily presumed to have all four meanings in the Church Fathers.

9Also, while I’m sure your high school English teacher was a lovely person, the definition of “allegory” that they gave you was almost completely wrong. Lord of the Flies is not an allegory; “The Metamorphosis” is not an allegory; The Chronicles of Narnia are not allegories; even Animal Farm is not an allegory. They all use symbolism, but there’s a different word for that—”symbolism”—of which allegory is a specific subtype, in which most or all of the characters are personified abstractions, normally engaging in a psychomachy. The only true allegories you’re likely to have read in high school English are the Inferno and Pilgrim’s Progress.

10One favorite example was one of the better-known provisions of kashrut: Most land animals can be kosher only if they are ruminants with cloven hooves. The fathers interpreted rumination, a.k.a. “chewing the cud,” as symbolic of meditation, and the cloven hoof as distinguishing good and evil. Any animal that did not do both could not be eaten by Jews; on the moral reading of the same text, any teacher or book that does not display both a subtlety born of meditation and a clear grasp of right and wrong should not be “consumed” by Christians.