Series Table of Contents:

Introduction (what sacred/liturgical time is and why we have it)

The Canonical Hours (the Catholic “clock”)

The Former Holy Week (pagan antecedents of the week)

The Seventh Day (the Judaic week and the Sabbath)

The Revelation of the Octave (the Catholic week)

To Everything There Is a Season (Easter computus; fourfold interpretation of Scripture)

⇒ The Waxing of the Sun (the literal/meteorological year; the yearly allegory of the life of Christ)

The Waning of the Sun (the spiritual life through the lens of the year)

A Time to Get, and a Time to Keep (liturgical seasons in the Anglican Use)

Interpreting the Year

So! Last time, we discussed the basic mechanics of the calendar (mostly solar, with a soupçon of lunacy1). Then—and I realize this may have seemed like a bit of a sharp turn!—had a run-down of the fourfold method of interpreting Scripture: literary, allegorical, moral, and mystical. What does that add up to?

The short answer is, I think the liturgical year operates on the same four interpretive levels as the Bible. The long answer is the rest of this post.

He Made the Stars Also

(The Literal Year)

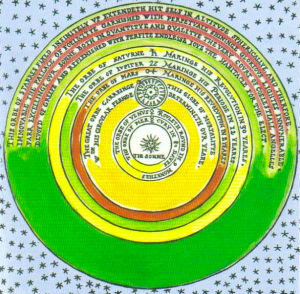

Diagram of the Copernican universe

(ca. 1576) by Thomas Digges,

its first expositor in English.

The function of a calendar is to describe a year, i.e. one complete circuit of the Earth around the sun. The liturgical calendar does this, same as any other calendar: winter (Christmastide, Epiphanytide, and Lent), spring (Eastertide and Pentecost to Sacred Heart inclusive), summer (the first half of the rest of Trinitytide), and autumn (the remainder of Trinitytide and Advent). The fact that four feasts occur near the solstices and equinoxes is probably not a coincidence, nor is the fact that the specific feasts which do so are what they are.

- Liturgical Winter.2 On 25 December, near the solstice and thus right as the Sun is about to start shining for longer periods and more brightly: the Nativity of Christ. (On analogy with the Moon, we might call this the “new Sun.”)

- Liturgical Spring. Around 25 March (held by tradition to be the actual date), near the vernal equinox and thus as light outstrips darkness in its share of the day: the Resurrection of Christ. (This of course would be the “waxing Sun.”)

- Liturgical Summer. On 29 June, near the summer solstice, and thus both on the most-sunlit day of the year and on the day when the darkness begins visibly to creep back: the martyrdom of SS. Peter and Paul. (This is the “full Sun.”)

- Liturgical Autumn. On 29 September, near the autumnal equinox and thus when darkness recovers its majority in the daily cycle: the feast of St. Michael the Archangel.3 (Obviously this is the “waning Sun.”)

There are our four seasons. They partly align with the “content” of the year, and used to be more marked. Back when England was predominantly agricultural, there were four weeks known as Ember weeks: these occurred shortly before, or at least close to, the solstices and equinoxes, and may have been linked to various types of harvests (and were common to the whole Latin Church, not just England). The Ember weeks were special times of prayer and penitence, akin to Lent but less intense. The Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays of Ember weeks were customarily marked by abstinence from meat and, on the Fridays especially, fasting.4 These times were considered specially suitable for ordaining priests.

15th-c. depiction of reaping wheat in stained

glass from Hertfordshire, probably from a

private house. Photo by David Jackson, used

under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license (source).

But of course calling these four seasons “liturgical,” as I have above, is a misnomer, in the sense that that’s not what the expression “liturgical season” means.

The Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End

(The Allegorical Year)

When we’re talking about Scripture, the allegorical meaning of a text is to be found in how it refers to the life and work of Christ. The same applies to the liturgical year. This is made explicit in the themes of each season, which are expressed in the Scripture readings, and even in the names of the liturgical seasons—in other words, the Church claims to offer the allegorical meaning of the weather (“without a parable spake he not unto them: and when they were alone, he expounded all things to his disciples”—Mark 4:34). What she offers in the shape of a liturgical year is the human life of Christ, both before and after the Ascension.

The Incredulity of St. Thomas (ca. 1602),

by M. Merisi da Caravaggio

As touched on last time, the liturgical seasons vary slightly between one tradition and another, though sticking to the Christmas-Easter-other structure. Listed strictly, the Anglican Use has nine very unequal and occasionally overlapping seasons, plus a tenth, the Triduum. This isn’t really a season per se, but it has to be classed by itself, and thus effectively ranks with them. (I’m leaving out unofficial subdivisions for the moment, mainly because they’re not structurally important.)

- Advent

- Christmastide

- Epiphanytide

- Shrovetide

- Lent

- Passiontide

- The Triduum

- Eastertide

- Whitsuntide

- Trinitytide

These align with these salient events in the life of Christ:

- His time in the womb of his Mother

- His birth and infancy

- His revelation to the Gentiles, baptism, and first miracle

- His early public ministry

- His Transfiguration and further public ministry

- His preparation for the Passion and entry to Jerusalem

- His institution of the Sacrament, his Passion, and his Resurrection

- His earthly time after the Resurrection; the ten days the cenacle5 awaited the Spirit

- The descent of his envoy the Spirit onto his emissaries

- The ongoing ministry of Christ through his Church until the Second Coming

Two Allegorical Digressions

To a certain extent, the Mass itself follows this same structure:

- First is the introit or processional hymn (note that this comes before we even make the sign of the Cross);

- then (save when it is omitted, as in Advent) comes the great hymn called the Gloria in Excelsis Deo;

- the Scripture passages are read, mostly in chronological order,

- followed by the more accessible homily and

- Creed, keeping step with Jesus’ gradual self-disclosure;

- the offertory follows, which prepares the sacramental elements;

- the consecration of the Eucharist “proclaims his death” (omitted only on Good Friday, when it is superfluous),

- and the Communion rite “confesses his Resurrection”;

- and finally, the assembly is blessed

- and sent forth.

Obviously you don’t need this map of the ritual to understand what’s happening during the Mass (though I find it illuminating). The point is to get used to interpreting things in reference to Christ, typologically, because that is the example the New Testament actually sets for us (and we may be sure that, to whatever extent the Apostles didn’t simply take this idea over from Judaism, they were taught it by Jesus).

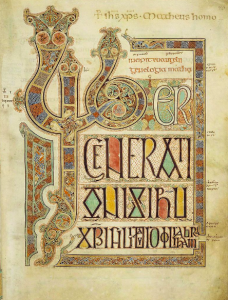

The beginning of Matthew in the

Lindisfarne Gospels (ca. 715-720).

You could even model the Bible itself on this pattern. Now, it takes some special pleading, but that doesn’t have to be a bad thing. It will be bad if you pretend that you got it from the text, rather than admit you’re bringing it to the text; but there’s a very simple way of avoiding that issue, which is not to tell lies. What you’re actually doing is experimenting with looking at Scripture in a fresh way. If the results do nothing for you, that’s fine—and if they net you something rather nice, you don’t have to consider it more important than “Oh, that’s rather nice.”

So in that spirit, consider the following lopsided profile of the Bible’s structure:

- The Torah

- The Prophets

- The Writings

- The Gospel of Matthew

- The Gospel of Mark

- The Gospel of Luke

- The Gospel of John

- The Acts of the Apostles

- The Epistles

- The Apocalypse

To say the New Testament gets the lion’s share (heh) would be putting it mildly—six individual books of it make up fully 60% of this outline. Still, I’m bold to suggest that there’s something interesting in the fact that we can arrange the Bible into two fairly natural sets of three, lying before and after the Gospels, and in the parallelism between the two sets—a description of some key parts of the early history of God’s covenant people (1 and 8), followed by several voices’ ethical and moral commentary (2 and 9), and further commentary of a more liturgical kind (3 and 10).6

But we’re here about the liturgy! Speaking of which, we have two further levels of woowoo left to apply to the calendar. We’ll do them next.

Footnotes

1In the ancient world, the moon—in Latin, lūna—was thought cause periodic fits of madness; lunacy literally means “moonliness,” though of course we’d probably say something “moonstruck-ness” in practice if this belief survived.

2Okay, light blue isn’t the same as white, but it’s not like I could put white lettering on a white background. No I’m not overthinking it! I didn’t bring it up, you brought it up

3A case could be made for other festivals as the prime markers of 3 and 4 here. The Nativity of the Baptist (24 June), which corresponds even better to Christmas, would work for 3 (and I’d honestly be inclined to treat both together as the solstice-marking observances). As for 4, the premier feast of September is really the Triumph of the Cross (14 Sept.); that’s a little early, but we might also consider Our Lady of Sorrows (15 Sept., if we’re willing to take a single day closer to the real equinox) or St. Matthew (21 Sept.)

4If you’re wondering why people would bother having a custom of not eating meat when they just weren’t eating anyway, the answer is that a conventional medieval fast was not absolute: a person could eat nothing for the full twenty-four hours, if they so chose, but the actual guideline was that the midday meal was not taken (breakfast was not normal in any case) and the evening meal was only taken after sunset. In other words, the modern relaxation of fasting norms did not relax nearly as much as its critics tend to suppose.

5This term refers to the “Upper Room,” where the Eleven, the Mother of God, St. Mary Magdalene and the other Myrrh-bearers, and the rest of the infant Church met daily, between the Ascension and the descent of the Holy Ghost. It comes from the Latin cēnāculum, based in turn on cēna “supper, dinner” and the diminutive suffix –culus, which could sometimes be extended to mean “place for” (and of course place names are easily transferred to name groups of people who frequent the place in question). The upshot of this, to my personal chagrin, is that a person who wishes to say the primitive Church met in a place they basically called “the Nook” cannot easily be proven wrong.

6If it sounds weird to call the book of Revelation liturgical, well, fair enough, it’s a weird book! However, I think that the liturgy as a means of God’s self-disclosure is one of the main lenses through which we’re meant to understand the book, and that later interpretations which have ignored that have confused the issue quite fantastically. For more on this, I suggest my three-part series from last August, “The Veiling of the Ark.”