(Should I Say It? It’s Such a Lame Joke. Yeah, I’m Gonna Say It)

This post is kind of a one-off. 15th August is the Solemnity of the Assumption, one of the greatest feasts in the Church’s year outside the Paschal cycle; the Gospel for the Assumption, as for many Marian feasts, comes from the episode early in Luke known as the Visitation. In the interest of variety, I therefore opted to translate the first reading instead. Usually, I’m in no position to do this, because the first reading usually comes from the Old Testament, and my Hebrew isn’t equal to the task. However, for Assumption, the text in question is from the Apocalypse, a.k.a the book of Revelation—the fun, crazy part of the New Testament, and also one that a lot of commentators are afraid to commentate on. To be fair to them, it is difficult to discuss this book well; but I think the reasons for that are actually quite different from what most people suppose, and much easier to address. That said, I have split this post into two on account of the difficulty! (If I’m lucky, I’ll be able to wrap up Part II and get it published tomorrow or not long thereafter. I’m accordingly planning to combine the Gospels for the 18th and 25th into one and postpone it slightly, probably into late next week.)

Our passage—because the USCCB hates having continuous readings like nuts in brownies, apparently—is Apocalypse 11.19a, 12.1-6a, and 10a-b. In my translation and commentary, I have included the intervening segments, and also allowed the voice in heaven speaking in 12.10 to finish its thought, carrying us to the end of v. 12 (with text not read in the liturgy in grey, as usual). I usually try and keep text and textual notes together, but I already had the translation done in any case and the Scripture itself is the main point, so I’m including it in this post as well.

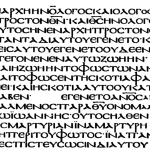

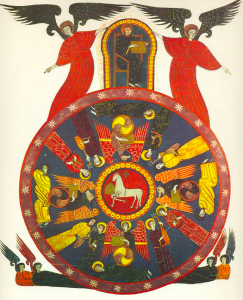

The breaking of the Sixth Seal (Rev. 6.12-17)

from the illuminated commentary of Beatus

of Liébana (ca. 750-780).

(Ahem.) “Apocalypse Now”

One of the reasons the Apocalypse is so famously difficult is that it belongs to a literary genre (also called apocalypse, or apocalyptic) that doesn’t exist any more. Specimens of it survive, of course, but people don’t write new works in the apocalyptic genre—in this, it’s not unlike the literary genre of allegory,1 save that you do get the occasional Hind’s Feet on High Places even nowadays, whereas the most recent apocalypse I could find any information about was from the 600s. To judge from surviving examples, the golden age of apocalyptic can probably be said to begin around the mid-third century BC, when I Enoch was composed, and to conclude in the late fourth AD with the (forged) Apocalypse of Paul.

In consequence, most of us don’t know how to read apocalypses. Their conventions and stock material, which would have made sense to a contemporary (at least one with a Judaic background), are opaque and confusing to us2—which is a little ironic, since the meaning of ἀποκάλυψις [apokalüpsis] is “unveiling” or “disclosure”! Let’s begin with a few clarifying points.

What Do an Apocalyptic Literature?

Detail from a miniature of the Assumption by the

Master of King James IV of Scotland,3 created

ca. 1510-1520. Note the angel at the lower left,

giving the Virgin’s belt to St. Thomas the Apostle.

First, it began as a specifically Judaic genre. Its sources may have been eclectic: e.g., Zoroastrian influence, on both this genre specifically and Judaism as a whole, is considered likely by many scholars. But it is a genre rooted in … well, I was going to say “the prophets,” and then I thought “the Torah” would be more accurate, and then I realized I didn’t want to de-emphasize the Deuterocanonicals too much (the books Protestants typically call “the Apocrypha”5)! The whole Catholic Old Testament is in play here, maybe more. Much of the imagery and language used to describe the heavenly Temple, e.g. in chs. 4-5 and chs. 14-15, is drawn from either the conclusion of Exodus or the later-dated prophets, chiefly Ezekiel, Daniel, and Zechariah. (In the former, take note of the vision of Moses, the description of the Tabernacle and its principal vessels, the description of the high priest’s vestments, and its completion and hallowing.)

Like prophecy, apocalypse is often assumed by modern readers to be about the future. There’s a sense in which this is true; but still, books are normally written to address their, you know, readers, in the present.6 The issue that typically gave rise to apocalypses was persecution, and since the genre was written to encourage and strengthen those in straits with God’s promises, it is “forward-looking.” But when a message is not for the present time, the usual heavenly policy seems to be to “seal up those things which the seven thunders uttered, and write them not.”

Besides that, apocalyptic shares elements and an atmosphere with Merkavah and Hekhalot mystical literature, topics I’ve touched on a couple of times here. These are Judaic mystical traditions, concerned with the glories and mysteries of God’s heavenly Temple and with the various names, functions, and powers of the hosts he is the Lord of; the Book of Enoch, or I Enoch,7 displays similar interests; its later companion III Enoch is definitely hekhalotic literature. In one sense, the New Testament book of Revelation is striking in how little attention it allots to the hierarchy of angels8—like the New Testament as a whole. The Apocalypse only directly names one, St. Michael (if St. Gabriel is present here at all, he’s incognito, and St. Raphael never even gets a namedrop outside of Tobit).

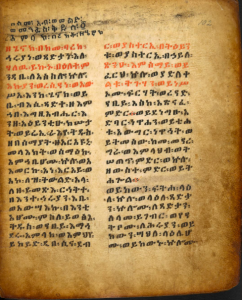

First page of a 16th-cent. manuscript of I Enoch, written in Ge’ez

(the liturgical language of the Ethiopic Christian tradition).

But the fundamental role of apocalyptic is to serve as a form of what’s called resistance literature. This is literature composed by a disadvantaged or oppressed group, with the purpose of helping to sustain that group through its suffering. The ἀποκάλυψις, the disclosure, involved was (among other things) a disclosure of God’s care for them and his promise to set things right in the end. It was a consolation and encouragement grounded in divine vindication; “though it tarrieth, wait for it.”

The Structure of the Apocalypse

Revelation, like the Gospel of John, is a very carefully constructed book, with (arguably) nine interlocking sections—a prologue, seven cyclical parts, and an epilogue. Not every part follows this pattern exactly, but in general, the rhythm of each section is:

- The idea of the cycle is introduced

- Most of the cycle is run through

- An interlude occurs, attending to a distinct idea (often picking up a motif from an earlier cycle)

- The cycle concludes, and becomes the setting of the following cycle

This is reproduced in a couple of ways at more “macro” levels of the book’s structure: first, the four sevenfold cycles (churches, seals, trumpets, and cups9) have an interlude of their own, between the trumpets and the cups; and second, that whole deal (sections II through VI) is then followed by an interlude before the final cycle presenting the Last Judgment. The narrative thus has a very labyrinthine feel; its complexity is the result of what is, in itself, relatively simple—like the complexity of a fractal. Even though most parts of it are susceptible to relatively straightforward analysis, the arrangement is intricate in the highest degree.

A depiction of the Mandelbrot set, a famous

fractal image—on magnification, every part

recreates the whole. Created by Wolfgang Beyer,

used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

The broad outline of the Apocalypse can be sketched as follows; our text comes from the two segments in bold.

I. Prologue—Alpha and Omega (1.1-8)

II. The Seven Churches (1.9-3.22)

…..A. Vision of the Son of Man (1.9-20)

…..B. Letters to the Seven Churches (2-3)

III. The Seven Seals (4.1-8.1)

…..A. The Throne Room and the Scroll (4-5)

…..B. The Breaking of the First Six Seals (6)

…..C. First Lesser Interlude: The Jewish and Gentile Elect (7)

…..D. The Breaking of the Seventh Seal (8.1)

IV. The Seven Trumpets (8.2-11.19)

…..A. The Preparation of the Trumpets (8.2-5)

…..B. The Sounding of the First Six Trumpets (8.6-9.21)

…..C. Second Lesser Interlude: The Measurement of the Temple (9.1-11.14)

…..D. The Sounding of the Seventh Trumpet (11.15-19)

V. Great Interlude: The Unholy Trinity (12-14)

…..A. The Woman and the Dragon (12)

…..B. The Beast (13.1-10)

…..C. The False Prophet (13.11-18)

…..D. The Lamb (14)

VI. The Seven Cups (15-16)

…..A. The Preparation of the Cups (15)

…..B. The Outpouring of the Cups (16)

VI. Babylon and the Beast (17.1-19.10)

…..A. Exposition of Babylon and the Beast (17)

…..B. Triumph Over Babylon (18.1-19.10)

VIII. The Last Day (19.11-22.7)

…..A. Armageddon (19.11-21)

…..B. The Millennium (20.1-10)

…..C. The Last Judgment (20.11-15)

…..D. The New Jerusalem (21.1-22.7)

IX. Epilogue—Alpha and Omega (22.8-21)

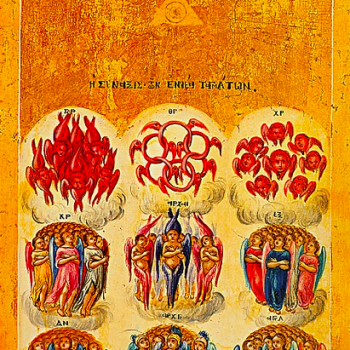

The sign of the Son of Man, also from Beatus

of Liébana’s commentary.

The open secret of the Apocalypse is, these images are liturgical. Nearly the whole book, remember, is taking place in the heavenly Temple. The seals, trumpets, and cups evoke the rituals, and even to a degree the structure, of the liturgy: the reading of Scripture, the playing of music, and the feast of the Eucharist; note also how in sections VII and VIII, the vindicated people of God are invited to “eat the flesh” of their vanquished enemies. (I gather he’s gone disappointingly trad in his attitude to the Holy Father lately, but Scott Hahn’s book The Lamb’s Supper is quite a good introduction to Revelation as a liturgical work.)

At the same time, sections III through VIII give us an outline of redemptive history.

- God’s plan is declared in the breaking of the seals, which allow the book to be opened—presumably the book of the Law (Judaism, even more so than Christianity, is now and was then a “religion of the book”; note, too, that only the Lamb can open or even look at the book).

- Foretastes of God’s plan are then given in the trumpets, which provoke signs similar to the cups, but less in degree (e.g., both the Second Trumpet and the Second Cup affect the sea, but in the cycle of the trumpets, only a third of the sea is turned to blood; the fullness of judgment is delayed). These may represent the prophets, culminating in the Baptist and followed by the next section.

- I’ve labeled this “the Great Interlude.” The Woman, arrayed as the “Daughter of Zion” from the prophets, gives birth to a “male child,” plainly corresponding to Jesus. After the child is “snatched up to God and his throne,” the confrontation between the Woman and her children on the one hand, and the anti-Trinity on the other, proceeds.

- Finally, God’s plan is accomplished in the outpouring of the Seven Cups, a traditional symbol of God’s judgment in the prophets (e.g. in Isaiah 51, Jeremiah 25, and Obadiah). After another interlude, the Last Judgment follows.

The Last Judgment (1541), by Michelangelo.

How does all this apply to our text? Well, in terms of the introduction-body-interlude-conclusion structure discussed above, we are seeing a transition: we begin with the conclusion of the third section, which is also the point where it blossoms into the fourth.

Revelation 11.19a, 19b, 12.1-6a, 6b-9, 10a, 10b-12, RSV-CE

Then God’s temple in heaven was opened, and the ark of his covenant was seen within his temple; and there were flashes of lightning, loud noises, peals of thunder, an earthquake, and heavy hail.

And a great portent appeared in heaven, a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars; she was with child and she cried out in her pangs of birth, in anguish for delivery. And another portent appeared in heaven; behold, a great red dragon, with seven heads and ten horns, and seven diadems upon his heads. His tail swept down a third of the stars of heaven, and cast them to the earth. And the dragon stood before the woman who was about to bear a child, that he might devour her child when she brought it forth; she brought forth a male child, one who is to rule all the nations with a rod of iron, but her child was caught up to God and to his throne, and the woman fled into the wilderness, where she has a place prepared by God, in which to be nourished for one thousand two hundred and sixty days.

Now war arose in heaven, Michael and his angels fighting against the dragon; and the dragon and his angels fought, but they were defeated and there was no longer any place for them in heaven. And the great dragon was thrown down, that ancient serpent, who is called the Devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world—he was thrown down to the earth, and his angels were thrown down with him. And I heard a loud voice in heaven, saying, “Now the salvation and the power and the kingdom of our God and the authority of his Christ have come, for the accuser of our brethren has been thrown down, who accuses them day and night before our God. And they have conquered him by the blood of the Lamb and by the word of their testimony, for they loved not their lives even unto death. Rejoice then, O heaven and you that dwell therein! But woe to you, O earth and sea, for the devil has come down to you in great wrath, because he knows that his time is short!”

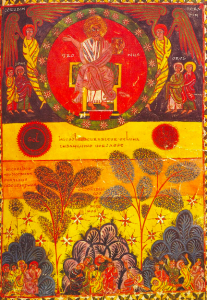

The adoration of the Lamb before the throne,

also from Beatus of Liébana’s commentary.

Revelation 11.19a, 19b, 12.1-6a, 6b-9, 10a, 10b-12, my translation

And the temple of God which is in heaven opened, and the Ark of his Testament was seen in his temple; and there were bolts of lighting and voices and thunderings and an earthquake and great hail.

And a great sign was seen in heaven, a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon was underneath her feet, and on her head was a crown of twelve stars; and she was with child, and cried out in her labor and was tormented to give birth. And another sign was seen in heaven—and behold, a great fiery dragon with seven heads and ten horns, and seven diadems on his heads; and his tail swept down a third of the stars of heaven, and they fell to the earth. And the dragon stood in front of the woman who was about to give birth, so that when she bore, he could devour her child. And she bore a son, a male, who was going to shepherd all nations by an iron rod; and her child was snatched up to God and to his throne. And the woman fled into the desert, wherein she has a place made ready for her by God, so that he can feed her there for a thousand, two hundred, and sixty days.

And there was war in heaven: Michael and his messengers waged war on the dragon. The dragon too began waging war, and his messengers, but they were not strong enough—their place is no longer found in heaven. And he was cast out, the great dragon, the primordial serpent, who is called the Accuser and Šâṭân, who wanders around the whole inhabited world—he was cast down to the earth, and his messengers were cast down along with him.

And a great voice was heard in heaven that said: “Now have come the salvation and the power and the kingship of our God, and the authority of his Anointed, because the slanderer of our brothers is cast out, he who slanders them in front of our God day and night. And they defeated him by the blood of the Lamb and by the word of their witness, and did not love their life to the point of death; rejoice over this, O heavens and you who dwell in them. Woe to the earth and the sea, because the Accuser went down to you in a great rage, seeing that he has little time.”

A 19th-century reproduction of an illustration

of the Mulier Amicta Sole (“Woman Clothed

With the Sun”) from the 12th-century Hortus

Deliciarum, an illuminated encyclopedia.

This wound up being a three-parter! Go here for Part II and here for Part III.

Footnotes

1Some of my readers may protest that high school took them through lots of allegories, like Animal Farm and Moby-dick. With apologies to your English teacher, who had a tough job, neither of these are allegories, nor are almost any of the books that were described to you as such. The defining traits of allegory are that its characters are (very specifically) personified abstractions, and the plot is generally a drama of personal or mystical growth. Best I can tell, the only genuine allegories that are still widely read are the Inferno and Pilgrim’s Progress.

2Why, yes, this is a direct cause of the existence of the Dispensationalist school of theology.

3This miniaturist’s identity is not known for certain (hence the circumlocution “the Master of King James IV”). However, he is agreed by art historians to have been part of the Flemish Renaissance, and what details we have about the Master apparently line up with Gerard Hourenbout. James IV of Scotland was quite an interesting figure in his own right. For example, he was the last monarch in the British Isles to die in battle, at Flodden, where the Scots fought forces led by the Queen of England, Katharine of Aragon4—yet it was also thanks to his marriage to Margaret Tudor, Henry VIII’s elder sister, that his great-grandson was able to claim the throne of England as King James VI and I (of Scotland and England respectively).

4Queen Katharine was regent in her husband’s absence, and the English victory at Flodden was attributed in part to the stirring speech she gave before the battle. Her fervor may have expressed loyalty to her husband; however, it’s also possible she felt personally invested. It doesn’t seem to be widely known, except among period historians, but Katharine had Plantagenet blood of her own: her maternal grandmother, Catherine of Lancaster, was the eighth (legitimate) child of John of Gaunt. This of course has nothing to do with our text; so come over here and stop me why don’t you, tough guy.

5As mentioned, the name for these books among Catholics is the Deuterocanon, i.e. “second rule” or “second canon.” Apocryphal literature is properly a much broader category, encompassing many works no branch of Christianity has ever treated as inspired. The Deuterocanical books are “second” because they are of late composition (mostly from 300-100 BC), and some were first written not in Hebrew but Greek, a major hindrance to their welcome in Tannaitic-era Judaism. Some of my Protestant readers may be keen to add that merely being quoted in the New Testament does not prove a book is inspired, which is perfectly true. I bring up the Deuterocanonicals not to open a polemic in their defense, but because they have an appreciable literary influence on the New Testament.

6Not to pick on the Left Behind series, but if Revelation really were a coded message about the U.N. Security Council or whatever, what sense would it make to give that message to the Church two thousand years before it could be either comprehensible or relevant?

7This is the “Enoch” notoriously quoted in the Epistle of Jude. Although some Jews and early Christians revered I Enoch (such as the Essenes, St. Clement of Alexandria, and Tertullian), most did not consider it inspired; however, in Ethiopia, the unusually isolated communities of Beta Israel and the Orthodox Tewahedo Church both esteemed I Enoch as sacred Scripture, as they do to this day.

8“The City Council would like to remind you about the tiered heavens and the hierarchy of Angels. The reminder is that you should still not know anything about this. The structure of Heaven and the Angelic organizational chart are still privileged information. Also, Angels aren’t real.” —Welcome to Night Vale Ep. 25: One Year Later.

9“Cups” is not so much a good translation as the least-unsatisfying of a list of poor translations. The Greek word is φιάλη [phialē], from which we get the word vial (or, in its archaic spelling, phial), which meant a shallow bowl or pan. Vessels of this sort were often used for drinking rather than eating in the ancient world; one of the minor ironies of language is that the term grail or graal refers specifically to the Holy Chalice in English, when its Latin antecedent (gradalis) meant “dish” and probably referred to the thing that held the bread! That said, our distinction between “drinks” and “liquid food” would probably have struck the ancients as hilariously and pointlessly stupid, so that our distinction between drinking vessels and bowls simply wouldn’t come up.