This post deals with the Gospel for the Eleventh Sunday after Trinity

(a.k.a. the Eighteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time),

as celebrated on 11 August, 2024 (Year B, week 19).

This continues from last week’s Gospel; here’s a link for any who missed it! I’m going to assume my readers have already read that part and its notes (and have therefore left out stuff about αἰών [aiōn] and the like that I might otherwise have made textual notes about).

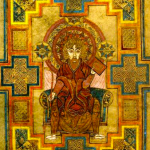

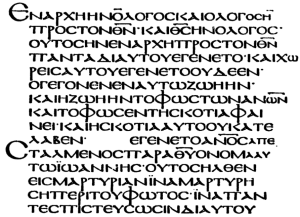

Beginning of the Gospel of John from Carl

Gottfried Woide’s facsimile of the Codex

Alexandrinus.1 Photo’d 2009, used under a CC

BY-SA 3.0 license (source—author unnamed).

John 6.36-40, 41-51, RSV-CE

a“But I said to you that you have seen me and yet do not believe. All that the Father gives me will come to meb; and him who comes to me I will not cast out.c For I have come down from heaven, not to do my own will, but the will of him who sent me; and this is the will of him who sent me, that I should lose nothing of all that he has given me, but raise it up at the last day.d For this is the will of my Father, that every one who sees the Sone and believes in him should have eternal life; and I will raise him up at the last day.”

The Jews then murmured at him, because he said, “I am the bread which came down from heaven.” They said, “Is not this Jesus, the son of Joseph, whose father and mother we know?f How does he now say, ‘I have come down from heaven’?” Jesus answered them, “Do not murmur among yourselves. No one can come to me unless the Father who sent me draws him; and I will raise him up at the last day. It is written in the prophets, ‘And they shall all be taught by God.’g Every one who has heard and learned from the Father comes to me. Not that any one has seen the Fatherh except him who isi from God; he has seen the Father. Truly, truly,j I say to you, he who believes has eternal life. I am the bread of life. Your fathers ate the manna in the wilderness, and they died. This is the bread which comes down from heaven, that a man may eat of it and not die. I am the livingk bread which came down from heaven; if any one eats of this bread, he will live for ever; and the bread which I shall give for the life of the worldl is my flesh.”m

John 6.36-40, 41-51, my translation

a“But I told you that even having seen me, you do not believe. Everyone my Father gives me, he brings to me,b and he who comes to me I will not cast out,c because I have come down from heaven not in order that I might do my own will but the will of him that sent me; this is the will of him that sent me, that all whom he has given me I will not destroy from him, but I will raise them on the last day.d For this is the will of my Father, that everyone who sees the Sone and believes in him should have eternal life, and that I will raise him on the last day.”

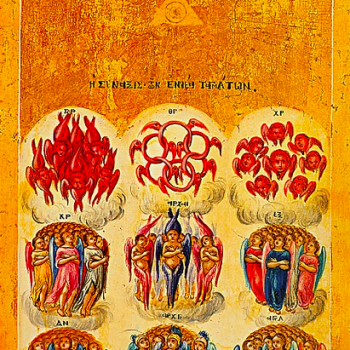

The Last Judgment, ca. 1100; ikon written by

John Tohabi, now housed at St. Catherine’s

Monastery on Mount Sinai.

Then the Jews began grumbling about him, because he said: “I am the bread that has come down from heaven,” and they said: “Isn’t this Jesus the son of Joseph, don’t we know his father and mother?f How now does he say that ‘I have come down from heaven’?”

Jesus answered and told them: “Do not grumble to each other. No one can come to me, unless the Father who sent me draws him, and I will raise him on the last day. It is written in the prophets: ‘And they will all be taught by God’g; everyone who listens to the Father and learns, comes to me. Because no one has seenh the Father, except him who isi from God—he has seen the Father. Amen, amen,j I tell you, he who believes has eternal life. I am the bread of life; your fathers ate the manna in the desert and died; this is the bread that comes down from heaven, so that anyone may eat of him and not die. I am the livingk bread, which has come down from heaven; if anyone eats of this bread, he will live forever, and the bread which I will give, it is my flesh,m for the life of the world.”l

Textual Notes

a. “But … : We pick up here—or, more exactly, we don’t pick up here, since this is not part of the Sunday reading; why, I’m not sure, as it doesn’t add all that much in length. In any event, the continuous text (using my translation) runs: I am the bread of life; he who comes to me will not be hungry, and he who believes in me will never be thirsty. But I told you that even having seen me, you do not believe. Everyone my Father gives me, he brings to me, and he who comes to me I will not cast out, etc.

b. will come to me/he brings to me: A small difference in wording, but one that, in my opinion, packs a good deal of theological punch! The former is a general statement about what will happen, and seems to imply more agency on our part; the latter points to an additional act on the part of the Father. If both my memory and my understanding serve, the distinction between the Father giving someone to the Son and bringing them to him corresponds to the distinction between electing and prevenient grace—I don’t clearly understand the Catholic approach to election, at least not once we get more specific than “election: it’s a thing that exists,”1 but prevenient grace is that grace which prompts conversion and belief. (It comes from a Latin verb, prævenīre, which literally means “to go before, precede, make way for.”)

St. Guy Heals a Possessed Man, 1474,

by Bavarian painter Gabriel Mäleßkircher

(selection from a surviving fragment of

a destroyed altarpiece).

c. cast out: Obviously this echoes the language of exorcism. A curious feature of John—who both contains more discussion of the devil than the Synoptics, and makes St. Mary Magdalene (who had been delivered from seven demons) one of his comparatively small number of named figures—is that, uniquely among the Gospels, none of his seven-to-maybe-ten2 miracles are exorcisms.

d. the last day: Judaic eschatology at this time was not entirely united and doctrinaire, but a majority of Jews believed that the soul is immortal, that there would be a resurrection of the dead in the Messianic age, and that there would be a final judgment. The Sadducees rejected these beliefs, on the grounds that they are not present in the (Written) Torah, which was the only Scripture they accepted, but they were exceptional. Despite their differences, the Pharisees and Essenes shared firm belief in this “immortality, resurrection, and judgment” eschatology.

e. sees the Son: Note the way the imagery of this passage echoes, and does not echo, that of the talk with Nicodemus in chapter 3. The timing (near Passover) is the same, and the central importance of “seeing” and “believing in” the Son is again stressed; here, however, although he would presumably have lifted up the bread while giving thanks (v. 11) before distributing it, he does not reiterate the language of being “lifted up” as he does with Nicodemus. Instead, the accent is increasingly on the fact that he will “give [his] flesh” to be eaten (which, even if this were interpreted as strictly and solely a metaphor, is at any rate the language of the Eucharist, as the language of chapter 3 is that of baptism).

There is also a dramatic difference in the direction and conclusion of the two scenes. In chapter 3, the interview ends with a gentle dismissal, and the next time we see Nicodemus (7.50-51), he seems at least as sympathetic to Jesus as before. Here—spoilers—we are building to a significant drop in the “headcount” of the infant Nazarene movement (v. 66); Jesus himself meets Peter’s moving affirmation of the collective faith of the Twelve (vv. 68-69: “Lord, to whom shall we go? thou hast the words of eternal life. And we believe and are sure that thou art that Christ, the Son of the living God”) with what seems like a bitter or tragic rebuff (v. 70: “Have I not chosen you twelve, and one of you is a devil?”).

The hostility of the religious establishment is a persistent element in all four Gospels. In John, from chapter 6 forward—exceptionally early in the narrative—we get a sense of walls closing in, the stakes getting incrementally, unrelentingly higher; and this turning point is focused upon what, in the Synoptics, is stated to be “the cup of the new covenant.”

Crowning of St. Joseph, ca. 1670,

by Juan de Valdés Leal.

f. the son of Joseph, whose father and mother we know/the son of Joseph, don’t we know his father and mother: A typical response attributed by the Synoptic Evangelists to the people of Nazareth. John contains no Nazareth “scene”; it is possible that some elements of Jesus’ visit there have been combined with this “bread of life” discourse (especially since Capernaum was Jesus’ Galilean “base” for a time). Compare the whole sweep of John 6, 7, and 8 with the single scene at Nazareth described in the fourth chapter of Luke.

g. And they shall all be taught by God/And they will all be taught by God: The quotation here is loosely phrased. This is not uncommon in quotations from this era; the concern was with getting the gist across more than the wording, unless for some reason the exact wording was vital. Furthermore, synagogue readings from Scripture, most of which was written in Hebrew, would normally be rendered in Aramaic (or sometimes Greek, if that were the main language of the local Jews) via what are called targumim, or less formally “targums.” We don’t need to get into full details about them now; suffice it to say, these were versions of the text that tended to lie somewhere between translation, paraphrase, and midrash, and which at first were strictly oral. The point is, precisely-matched wording is hardly to be expected in every Biblical allusion. Nonetheless, this wording is nearly identical to that of Isaiah 54.13; given the “new covenant” language that Christians had learnt to associate with the Eucharist long before John was written, Jeremiah 31.33-34 is another plausible source.

h. Everyone who has heard … the Father comes to me. Not that anyone has seen the Father/everyone who listens to the Father … comes to me. Because no one has seen the Father: Hearing and vision (again with the sensory imagery!) are recurring motifs in Johannine literature. We’ve touched before on vision. One of the things that’s intriguing here, though, is that hearing and vision are clearly meant to be symbols of, or analogies for, distinct facets of how we relate to God. John emphasizes more than any other New Testament writer (indeed, more than most Old Testament authors) that “no one has ever seen God” (1.18), yet it’s also clear that “my sheep hear my voice” (10.27) and that “the hour is coming, and now is, when the dead shall hear the voice of the Son of God” (5.25).

I think the distinction the Fourth Gospel is conveying here is something like the difference between our powers of apprehension and imagination. (Whether you’ve heard these terms for the two categories or not, I guarantee you’re familiar with the distinction: it’s that between grasping something in the abstract and being able to “make it real to ourselves.” E.g., most of us apprehend what is meant by a phrase like “fourteen billion dollars,” and could do arithmetic about how much compound interest should blah blah blah; but I expect few if any of us can really imagine fourteen billion dollars, in terms of how much of our basement it would fill or how many dozen-can boxes of Dr. Thunder it could purchase.)

For those not familiar with Dr. Thunder.

(Image provided for under fair use.)

The obvious difference between the two, for most of us, is that speech is conveyed through the ears, whereas appearance comes through the eyes. (Obviously the existence of writing mucks up the analogy a little, but it’s still true that you cannot take in written information at a glance the way you can take in audio information the moment you hear it.) Evidently the message borne by the Son, or that subsists in the Son as the Logos, is something that can be conveyed easily—but perhaps, in some sense, that which is given through vision can come only through that means? “Brethren … when he appears, we shall be like him, for we shall see him as he is” (I John 3.2): a transformative knowledge, in any case.

This last bit may be a rabbit trail; but I have a curious hunch that the transformative power here—which seems in some sense to be the same as the unseen-ness of God that brooks no exception but the Son—does not mean anything so obvious and edifying as “the kind of knowledge you can’t help but act on.” Now, cards on the table: I have a pronounced dislike of obvious and edifying meanings, as they almost invariably leave me with a cheap aftertaste, so I’d be inclined to look for something more “magical” in any case. But it also makes more sense to me. The knowledge of God couldn’t be like the knowledge of anything else; he’s too different from everything else for that to make sense. Nor is this notion really mine. C. S. Lewis put it very well (this passage is at first addressing what feels like an equally and opposite-ly transforming knowledge of evil):

As he lay there, still unable and perhaps unwilling to rise, it came into his mind that in certain old philosophers and poets he had read that the mere sight of the devils was one of the greatest among the torments of Hell. It had seemed to him till now merely a quaint fancy. And yet (as he now saw) even the children know better: no child would have any difficulty in understanding that there might be a face the mere beholding of which was final calamity. … [Likewise] there is one Face above all worlds merely to see which is irrevocable joy[.]3

i. is: Here, I was tempted to get wonky and translate the text as “except him who exists from God” instead. This is because the Greek, a little unusually, bothers with a verb4 that it could have skipped with no real effect on the text. The phrase is ὁ ὢν παρὰ τοῦ θεοῦ [ho ōn para tou theou], or hyper-literally “who is from the5 God.” That ὢν, “is” (or more strictly “existing”), doesn’t need to be there: ὁ παρὰ τοῦ θεοῦ would be equally acceptable. This suggests ὢν may be there for emphasis, and/or in alignment with the elevated language of the prologue (1.1-18), in which the Logos is with God, and is God, and makes the invisible God known to us below. However, this shouldn’t be pushed too far. Including ὢν here is mildly unusual, not stylistically bizarre; if it’s meant to say something, it says it subtly. Moreover, given Johannine Greek in general is a little odd and a little unpolished, a minor oddity like this isn’t likely to be “load-bearing.”

j. Truly, truly/Amen, amen: “Amen” is ultimately from Hebrew אָמֵן [‘âmên], which comes from a radical6 (א-מ-ן [‘-m-n]) that encodes meanings of loyalty, firmness, faithfulness, and dependability. It is, of course, one of several words from Hebrew that have traditionally been “imported” rather than translated by Christians of many languages. (The belief in some circles that “amen” is derived from the name of the Egyptian deity Amun, while not impossible, is highly unlikely, as that name is derived from a different radical.)

k. living: Jesus uses two closely related phrases in this chapter: “I am the bread of life” and “I am the living bread.” When I first noticed this, I assumed that the two wordings would give subtly differentiated meanings (e.g., a minor variation of emphasis in the message conveyed). Looking over the text, though, I think “living bread” is not so much a variant upon the same theme as it is an escalation of his rhetoric. Vv. 35 and 48 both contain the “of life” wording, followed by “living” in v. 51, and shortly thereafter by “the bread that I will give is my flesh … for my flesh is meat indeed” (vv. 51, 55).

Combining the ideas of “bread” and “flesh” just

made me think of a calzone. Probably go well

with a nice cold Dr. Thunder.

l. the life of the world: As the Creator of all being, God has always been, metaphorically, the moment-by-moment sustenance of all creation. However, this is rarely expressed by food-based analogies: the most common parallel would probably be the ground, on which we rest moment to moment. The specific choice to discuss not just a “ground of being,” but a food of life, points in the direction of the intelligent and personal.

m. flesh: The Greek term σάρξ [sarx] (again recalling the prologue, v. 14) quite literally means “meat”; it’s descended from an Indo-European root meaning “cut.”7

Footnotes

1Election is also known under the mildly misleading name predestination (mildly misleading, insofar as that word is widely assumed to indicate determinism or fatalism). This doctrine is—or involves—the idea that the Church is not only God’s people but God’s chosen people; her nature and fate are matters of divine decree. Insofar as it is pertinent to the spiritual life, I think the point of the doctrine is that it replaces mental pictures like “celestial bureaucracy” or “the Fates, but male” with the picture of a Person who wants us around for a set purpose. However, the theology here, or at any rate the discussions of that theology that I’ve read, are too subtle for me to make sense of, so I’ll say no more than that.

2Before the Cross, the Gospel of John contains seven “signs,” seven miracles (beginning with the changing of the water into wine at Cana and concluding with the raising of Lazarus). The Resurrection thus makes the eighth, and the miraculous catch of one hundred and fifty-three fish in chapter 21, a ninth. If we wanted to make John contain an even ten miracles, there are a few possible candidates: his apparently supernatural knowledge of the history of the woman in Sychar in chapter 4, his prophecy of St. Peter’s martyrdom also in 21, the Incarnation itself as alluded to in chapter 1, and the Ascension hinted at in chapter 20, are all arguable candidates.

3Where else but Perelandra, ch. 9.

4Well, technically it bothers with a participle; a participle is a verbal adjective (the forms that end with –ing or –ed in English can function as participles), when the action of a verb is viewed in light of how it modifies the noun, while of course still being an action and therefore still having verbal traits like voice and tense. Greek has a great abundance of participles, and frequently employs them where English would use a verb. (The –ing form can also be a gerund, or verbal noun, when the action of a verb is viewed as a thing.)

5The definite article here is not significant. Greek often uses the definite article where English would omit it (and occasionally drops it where we would have it); even proper names in Greek frequently take the article.

6In Indo-European languages, words are normally derived from roots. Roots are sequences of both consonants and vowels that encode some meaning; they can often be used bare, and most can prefixes and suffixes attached to them as well to derive other related words. For instance, from the root light, if we approach it as a verb, we can create a noun by adding the agent suffix –er: lighter, “thing that lights”; or, if we approach it as a noun, we can pluralize it with the suffix –s to discuss several lights. Semitic languages don’t quite work this way. Instead of roots, they use radicals. Radicals are groups of consonants only (usually three, sometimes two) that encode a general concept. Words are made by inserting vowels in specified patterns, and sometimes also adding prefixes or suffixes. For instance, in several Semitic languages, the radical k-t-b encodes the general concept “writing.” Inserting one set of vowels to make kitub gets us “a book,” while another set that makes kataab will be “books” in the plural, and yet a third set plus a prefix will make a maktab, “a school” (a place for writing, so to speak).

7That PIE root, though I expect people will think I’m making this up, is: twerk-.