This post deals with the Gospel for the Tenth Sunday after Trinity

(a.k.a. the Eighteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time),

as celebrated on 4 August, 2024 (Year B, week 18).

Talk Versus Homily

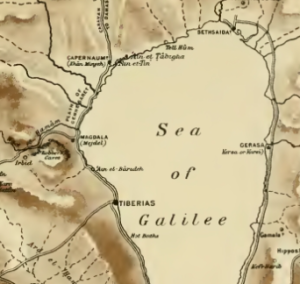

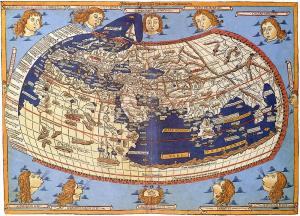

Portion of a map of the area around the Sea of

Galilee. Note Bethsaida to the north and

Capernaum on the northwestern shore.

The miraculous feeding took place somewhere near Bethsaida,1 the hometown of SS. Peter, Andrew, and Philip. With this passage, we move to the “Bread of Life” discourse, which was delivered in the synagogue at Capernaum. This may be the town Peter’s wife was from, since he lived there when Jesus’ ministry began, and served as Jesus’ informal base of operations in the Galilee. Before jumping in, I want to make one note about the style of the text.

The rhetorical difference between John and the Synoptics is quite marked in the various discourses John contains—so much so that it has been suggested John is less reliable. The way New Testament scholars phrase this is normally something like “the Fourth Gospel is the fruit of long theological reflection by the hand of a [insert cardinal number of choice]-generation Christian rather than an eyewitness,” but the drift is that these homilies could hardly have come as they are from the lips of Jesus when his style is so different in the Synoptics—the marked absence of parables (though not of figurative language) from John being just one instance of how much they diverge. At least, this used to be the conventional view; the past few decades have seen a glacially slow, but appreciable, shift toward dating all of the New Testament earlier and admitting more in the way of eyewitness testimony in the Gospels, if only as a “substrate of primitive tradition” (a soothingly polysyllabic phrase which we can surely allow to comfort the delicacy of the New-Testament-scholarly constitution).

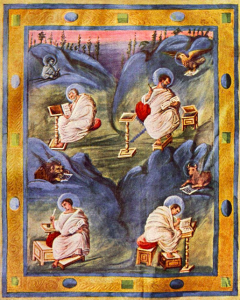

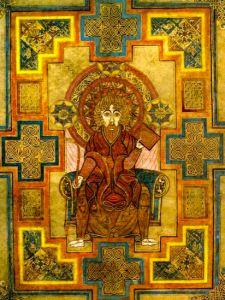

Folio from the Aachen Gospels depicting

the Four Evangelists, created c. 820.

Along these lines, there is an alternative to the fruit of long theological reflection. Dorothy Sayers, in Creed or Chaos? I think, pointed out that it would be very natural for sermons, or at least sermon-like addresses, delivered in synagogues or in the Temple, to differ a good deal from the open-air talks that form the bulk of the doctrine recorded in Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Think it out. Nearly all the teaching in John can be classified under one of three forms:

i. Homilies, like this discourse seems to be. (Given the sabbath was a fixture of Judaic life, Jesus may have planned these homilies in much the same way a modern pastor would.)

ii. “Cross-examinations” or debates back and forth. We find these in chapters 5, 7, and 8. Synagogues and the Temple were, after all, full of his theological opponents, whether we’re talking about Pharisees of an anti-Nazarene bent or, in the Temple specifically, Sadducees.

iii. Private conversations. Most of these as recorded in John are held with his own disciples and are relatively short (the “maundy” discourse of chapters 13-17 being an eye-catching exception to the latter rule). Chapters 3 and 4, however, record such conversations with two other people, bracketing the Baptist’s final testimony (3.27-362): Nicodemus, an educated Pharisee and member of the Sanhderin; and the Samaritan woman Jesus met at the well in Sychar (implicitly the opposite of Nicodemus in most ways, come to think of it3).

Papyrus 1 (according to the Gregory-Aland

numbering system), a mid-third-century

fragment of Matthew. Currently housed at the

Univ. of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia.

Now contrast those settings with what the Synoptics bear witness to. In them, we find parable-laden talks, often given on lakeshores and hillsides. Their audience would likely have included orthodox and observant Jews; but the crowd would be much more mixed than sabbath congregants or festal visitors to the Temple. Less-observant Jews—”the lost sheep of the house of Israel”—might not dare darken the door of their local synagogue, or might not be ritually pure enough to come further into the Temple than the Court of the Gentiles, but they would still mill around outdoors like anybody else, particularly if their work was outside, as it was for all agricultural laborers and many others as well.

And speaking of Gentiles, these crowds could also include Syro-Greek locals, Roman soldiers, the occasional merchant from nearly anywhere, and Samaritans from villages near the borders of Judah proper and the Galilee, too. We should expect both the material and the manner of a lecture given to such a different, and variegated, audience to be distinct from the specifically religious, purpose-gathered audience of lectures given at the “local parish.”

John 6.24-35, RSV-CE

So when the people sawa that Jesus was not there, nor his disciples, they themselves got into the boats and went to Capernaum,b seeking Jesus.

Southern region of the Sea of Galilee. Photo

by Zachi Evenor, used under a CC BY-SA

2.0 license (source).

When they found him on the other side of the sea, they said to him, “Rabbi,c when did you come here?” Jesus answered them, “Truly, truly, I say to you, you seek me, not because you saw signs, but because you ate your fill of the loaves. Do not labor for the food which perishes,d but for the food which endures to eternale life, which the Son of man will give to you; for on him has God the Father set his seal.”f Then they said to him, “What must we do, to be doing the works of God?” Jesus answered them, “This is the work of God, that you believe in him whom he has sent.” So they said to him, “Then what sign do you do, that we may see, and believe you? What work do you perform? Our fathers ate the mannag in the wilderness; as it is written, ‘He gave them bread from heaven to eat.’” Jesus then said to them, “Truly, truly, I say to you, it was not Moses who gave you the bread from heaven; my Father gives you the true bread from heaven. For the bread of God is that which comes down from heaven, and gives life to the world.”h They said to him, “Lord,i give us this bread always.”

Jesus said to them, “I am the bread of life; he who comes to me shall not hunger, and he who believes in me shall never thirst.

John 6.24-35, my translation

So when the crowd sawa that Jesus is not there, nor his disciples, they got into the little boats and came to K’far Nachum,b looking for Jesus. And finding him across the sea, they said to him: “Rav,c how did you get here?” Jesus answered them and said: “Amen, amen, I tell you, you are looking for me not because you saw the signs but because you ate of the loaves and were filled. Do not work for perishabled food, but for food that will stay on into eternale life, which the Son of Man will give to you; for that man, God the Father sealed.”f

Then they said to him: “What should we do, that we may do the deeds of God?” Jesus answered and said to them: “This is God’s work: that you should believe in him whom he sent.”

Then they said to him: “Then what sign do you perform, so that we may see it and believe in you? What deed? Our fathers ate the mannag in the desert, just as it is written: ‘Bread from heaven he gave them to eat.'” Then Jesus said to them: “Amen, amen, I tell you, Moshe has not given you bread from heaven, but my Father will give you true bread from heaven; for the bread of God is he who comes down from heaven and gives life to the world.”h

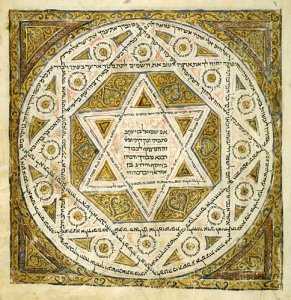

Folio 474a from the Leningrad Codex, the

oldest surviving complete manuscript of

the Tanakh in Hebrew.

Then they said to him: “Sir,i always give us this bread.” Jesus said to them: “I am the bread of life; he who comes to me will not be hungry, and he who believes in me will never be thirsty.”

Textual Notes

a. saw: This word is not difficult or unusual in context, but it affords us an occasion to consider some of the Fourth Gospel’s symbolism. Sight, like light, is a major motif. This could be explained on linguistic grounds if we wished: several Indo-European languages use a verb, or a form of a verb, that originally meant “to see” but had come to mean “to know,” or sometimes other cognitive words. The modern English “wit” goes back to the same root as the Latin vidēre, “to see,” and Latin also used vidēre in the passive voice to indicate “to seem, appear” (as in the normal openings of the articles in the Summa, “It would seem that such-and-such is the case”). The Greek cognate was εἴδομαι [eidomai], or εἶδον [eidon], used here; meanwhile the perfective-aspect form of the same root, οἶδα [oida], meant “to know” in ancient Greek.4

However, this is not just a linguistic curiosity. It reflects the author’s broader outlook. Remember, John is the only canonical evangelist who has anything positive to say about faith that is in any sense “based on” miracles, which he presents as “evidence for the defense,” so to speak; he is also the author of these verses:

That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon, and our hands have handled, of the Word of life; (for the life was manifested, and we have seen it, and shew unto you that eternal life, which was with the Father, and was manifested unto us;) that which we have seen and heard declare we unto you, that ye also may have fellowship with us: and truly our fellowship is with the Father, and with his Son Jesus Christ.

—I John 1.1-3

St. John in the Book of Kells, ca. 800.

There’s a simplicity, almost a naïve quality even, to the psychology of John. It would be wrong to say that he thought seeing was believing; he knew from experience that that wasn’t true. But—and lest I be misunderstood, in my opinion innocence is a positive quality, and the adjective a compliment—he is perhaps the only author of Scripture who is innocent enough to be flabbergasted by the fact that seeing is not believing.

Jesus said unto them, “Yet a little while is the light with you. Walk while ye have the light, lest darkness come upon you: for he that walketh in darkness knoweth not whither he goeth. While ye have light, believe in the light, that ye may be the children of light.” These things spake Jesus, and departed, and did hide himself from them.

But though he had done so many miracles before them, yet they believed not on him: that the saying of Esaias the prophet might be fulfilled, which he spake, “Lord, who hath believed our report? and to whom hath the arm of the Lord been revealed?” Therefore they could not believe, because that Esaias said again, “He hath blinded their eyes, and hardened their heart; that they should not see with their eyes, nor understand with their heart, and be converted, and I should heal them.” These things said Esaias, when he saw his glory, and spake of him. Nevertheless among the chief rulers also many believed on him; but because of the Pharisees they did not confess him, lest they should be put out of the synagogue: for they loved the praise of men more than the praise of God.

Jesus cried and said, “He that believeth on me, believeth not on me, but on him that sent me. And he that seeth me seeth him that sent me.”

—John 12.35-45

This is not the last time in this chapter that the motif of vision, and its remoter implications, will come up in this chapter.

b. Capernaum/K’far Nachum: Like the element beth– in Hebrew and Aramaic—Bethany, Bethesda, Bethlehem, etc.—the word k’far meant “village.” Nachum, besides meaning “consolation,” may also have been a reference to the prophet Nahum. His book tells us he was an “Elkoshite,” or Alqoshite, but it isn’t clear whether his Alqosh and the modern settlement of Alqosh, located in northern Iraq, are the same place (though the synagogue of the Iraqi Alqosh, now sadly in disrepair, does ostensibly contain the prophet Nahum’s mausoleum).

The modern Eldridge Street Synagogue in

New York City, built 1886-1887. Photo by

Rhododendrites, used under a CC BY-SA

4.0 license (source).

c. Rabbi/Rav: I’ve made something of a judgment call here. The word rabbi (which of course is still in use) is Aramaic in origin, whereas rav is Hebrew; given the prestige of Hebrew, rav is broadly considered the more formal of the two titles (if I’m rightly informed). But the word in the Greek text is the Aramaic one, not the Hebrew. Here’s why I decided to render the text this way.

Christians are used to thinking of clergy and teachers in largely similar terms. The rabbinate, both in the time of Jesus and now, was not the same office as the priesthood; that was passed down strictly through the Levites, whereas in principle any (male) Jew could be appointed a rabbi. However, like Christian priesthood—which, historically speaking, is a backwards way of putting it, but never mind!—the rabbinate was also passed down by ordination (סְמִיכָה [s’mikhah] in Hebrew), the succession of which was traced back to Moses and the Seventy Elders.6 The procedure followed in Palestine was that, after a substantial education in the Torah (both its Written and Oral components), a court of at least three judges, at least one of whom had to have been ordained himself, would pronounce a candidate worthy, after which he was considered ordained and could use the title “Rabbi.” S’mikhah often involved laying hands on the ordinand, but this ritual was not necessary; in fact, the panel of judges didn’t even need to have the ordinand in their presence for the pronounced ordination to be valid. (This contrasts with the Christian sacrament, in which the laying on of hands is an essential element; there are other ordinatory rituals, like prostration, that are not strictly required. That said, I do wonder whether the tradition that it requires three bishops to ordain a new bishop owes anything to s’mikhah.)

But I’ve specified that this is the procedure which was followed in the Holy Land. The communities of the Jewish Diaspora—which even at this time may have been the greater portion of the Jewish population; at minimum, they reached from Rome to India west to east, and from the Black Sea coast to Ethiopia north to south—didn’t always follow quite the same rules as those in Palestine, or as each other.7 Babylonia in particular was an independent center of Judaic learning, and had its own manners and customs. One of the differences was that Babylonian sages, though they received an education that qualified them in principle to be ordained as rabbis, did not habitually travel to the Holy Land to receive s’mikhah proper; accordingly (if my source is correct), rather than using “Rabbi,” a Babylonian Jew would normally use the title “Rav.”

Central Synagogue of Aleppo, Syria—5th

century. Photo by Govorkov, used under

a CC BY-SA 2.0 license (source).

For my purposes, this therefore allows rav a useful degree of respectful ambiguity. I’ve never heard of a source claiming that Jesus received s’mikhah; if there is one, that wouldn’t shock me, but the only professional background Jesus is clearly recognized as having in the Gospels is carpentry (touched on in the Gospel of a month ago). Being unable to say for certain either way, rav, which might describe a formally ordained rabbi or one recognized as such “by acclamation,” so to speak, therefore struck me as a good compromise.

d. which perishes/perishable: In this case (and it does not escape me that I’ve now said this a lot), I broke my own rules a bit, in being both less literal than I could have been and even in being less literal than the RSV. The verb used here is the passive-voice form of ἀπόλλυμι [apollümi], “to destroy.” Eventually, the passive and active forms of ἀπόλλυμι came to function almost as independent words, and it is normal to use the active-voice verb “perish” in English translations from Greek. However, I’ve gone a step further, for no better reason than that the expression “perishable foods” is such a natural and recognizable expression in English, and seems like the kind of play on words Jesus is employing here.

e. eternal: This term is derived from αἰών [aiōn], which often means “world,” usually in the temporal sense (e.g. “the ancient world”). It is, additionally, one of several words in New Testament Greek that makes me want to tear my hair out, because it’s straight-up immune to the rules I want to apply as a translator. I learned this from one of my favorite books, C. S. Lewis’s brilliant and shamefully ignored Studies in Words.8 The following comes from the chapter “World” therein, beginning from a point where he is explaining one of the four Greek words which is rendered in English as “world.”9 (I’ve abridged the text in several places, but, so as not to annoy the eye, have noted this with ellipses only for long gaps.)

Aion can mean simply life; it can also mean “the sort of life one has,” one’s lot or fortune. … Out of this trunk two strangely different branches grow. On the one hand, like World, aion can come to mean “indefinite time” or “ages and ages.” … For [Plato] it means “eternity” in the strictest sense; not indefinite nor even infinite time but the timeless. Time is a model of aion because it attempts, by incessantly replacing its transitory “present moments,” to symbolize, or parody, the actual plenitude of changeless reality … Hence in Shakespeare time is “thou ceaseless lackey to eternity.”

On the other hand, aion, especially among those who had a Jewish background, developed the sense of epoch or period with the fullest possible change of meaning. … Aiones differ from the “periods” used by our historians because their diversity is far greater, and also (more importantly) because the later aion does not grow out of the earlier by any natural development. The new aion is not so much a new act as a new play. … No people were more haunted by the conception of aiones than the Jews; and the Jews never more haunted than during the two centuries that preceded the Christian era. These are the age of Apocalyptic …

Both these senses of aion are used in New Testament Greek. Thus es ton aiona “into the aion” means “forever,” “eternally,” and the adjective aionios means “eternal” or “everlasting.” But side by side with these we find dozens of passages where “this aion” or “this present aion” is the very reverse of eternal, being contrasted with an aion that is “to come.”

Signet ring of Pharaoh Tutankhamun (1341-1323

BC) at the Louvre; note the cartouche, meant to

protect the pharaoh’s ren. Photo by Guillaume

Blanchard (CC BY-SA 1.0 license: source).

f. set his seal/sealed: Seals, such as signet rings, were a vital means of authentication in the ancient world: distinctive, fast to use, easy to verify, and costly to fake. The idea was that the user would press the seal into a soft substance that would retain the shape as it hardened; the earliest seals, in Sumer, were typically used on clay, while by Roman times wax was more normal. To help maintain their uniqueness (and thus their usefulness), signet rings in particular were normally destroyed upon the death of their owner—a practice still followed with the Ring of the Fisherman, the signet ring used by the pope.

g. manna/manna: I’ve set manna in italics on the grounds that it isn’t a Greek word. The explanation given in the Torah, probably a folk etymology, is that when the people first saw it, they said מָן הוּא [mân hu’], “What’s that?”—just what every parent wants to hear when setting food in front of their child. If I were translating a Hebrew text, and Hebrew were therefore the “English equivalency” language I were aiming for (as Greek in fact is here), my ideal translation for the word would be whatsit.

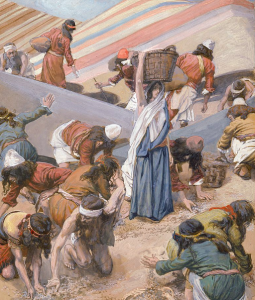

The Gathering of the Manna

(1902), James Tissot

h. world: Another “problem child” in New Testament vocabulary. In the chapter I quoted from C. S. Lewis above, he notes how its usage, within the Johannine books alone, spans the extremes of “God so loved the world” and “Love not the world.” Besides αἰών, which we’ve already tackled, the typical words for “world” in Greek are: γῆ [gē] “earth, land, country” (as in geography); οἰκουμένη [oikoumenē] “inhabited world,” a term that later came to denote the territory of the Empire particularly (whence ecumenical); and our concern in this passage, κόσμος [kosmos] “universe, world.”

Κόσμος is derived from the verb κοσμέω [kosmeō], with the primary meaning “to order, arrange” and a secondary meaning “to beautify,” a route through which it gave us the word cosmetics. This semantic movement, from the idea of order to the idea of beauty, appears in both Greek and English. The verb “to dress” is an excellent example; it has medical, culinary, agricultural, metallurgic, and even military meanings (many of them now fossilized or in disuse), which are for the most part older than the meaning “to put clothes on”: one can dress wounds with bandages, or a salad with a sauce, or an impure batch of flour, or an animal carcass, or ores before casting, or a line of soldiers so that they are at a regular distance from each other.

As C. S. Lewis points out, the variety of words for the concept “world” afforded the authors of Scripture a perfect way of keeping the positive, negative, and neutral meanings of “world” discrete: e.g., the “world” which God loves, his creation and especially the people, might have been denoted with κόσμος, while the evil that afflicts us in the sense of “the world, the flesh and the devil”—a thing unique to this age, “this present darkness”—could have been signified by αἰών, say, and γῆ perhaps used when neither evil nor good was really the point.

Of course, the authors of Scripture did nothing so neat, and freely used all four words (but especially αἰών and κόσμος) in both good and bad senses. This is probably partly because, in its Koiné phase (ca. 300 BC-600 AD), Greek was not the rich and elegant language it had been in the hands of Æschylus or Thucydides; it was a lingua franca, used anyhow by people of all sorts of linguistic and cultural backgrounds, including a large proportion of non-native speakers: Arabs, Armenians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Brythons, Cappadocians, Chaldæans, Cypriots, Egyptians, Epirotes, Etruscans, Gauls, Germans, Iberians, Idumæans, Illyrians, Medes, Persians, Phoenicians, Sicilians, Thracians, Umbrians—and of course Jews.10 Nuance, in Koiné, wasn’t something the language was going to do for a writer; there were too many influences coming in from without.

i. Lord/Sir: Here, I’ve veered slightly away from my usual one-word-for-one-word standard. In older English, “lord” could be used more loosely (originally it referred to any householder), but today, it tends to have exclusively aristocratic or religious connotations. In America in particular, the oldest continuous democracy in the world (to my knowledge), addressing strangers as “my lord” is done only by people affecting a bad Cockney accent—the very notion of lordship feels literally foreign to us.

The respectful forms of address in a number of other languages (especially those of democracies that are younger than our own, and/or became democracies without ceasing to be monarchies) coincide with some general aristocratic title. The Italian signore and the Spanish señor are good examples; so, incidentally, is the Greek word κύριε [kürie], which is the reason behind that screenshot that made the rounds a year or two ago, where Google translate rendered Kyrie eleison as “sir, take it easy.” Of course, our basic respectful form “sir” also used to be something with a little more gravitas, being a slightly worn-down version of sire, and both are derived (through French) from the same Latin root senior “elder” that gave us signore and señor; so there’s a good history-of-language case for using “sir” to translate κύριος when used for direct address.

Arrival of a Caravan Outside the City of

Morocco, ca. 1875-1890?, by American

painter Edwin Lord Weeks.

(A Ridiculous Proportion of) Footnotes

1Bethsaida (in Aramaic, בֵּית צַידָה [Beyt Tsaidah]) means something like either “House of the Fisherman” or “House of the Hunter”; given the importance of fishing in the region, I’m guessing the first meaning is the pertinent one. Its exact location has not been preserved, though descriptions in Josephus and Pliny the Elder give us an idea, and a small number of archæological sites have been determined to be plausible sites for the town. (We’ll be getting to what Capernaum means.)

2Many translations present verses 31-36 as direct theological commentary by the author of the Gospel. I find this an unsatisfactory reading. It’s not impossible, but it’d be clumsy to drop out of quotation without any direct signal—i.e., it’d be clumsy communication; John sometimes has clumsy grammar, but that’s different: a strictly technical flaw, defined by the “rules” of the language an author is writing in, many of which are a little arbitrary. Moreover, it wouldn’t match other places where the author editorializes, where the break is much more clearly indicated (e.g. in the latter half of chapter 12). Understanding these six verses as further teaching from the Baptist seems like a much better solution to me.

3Really, though! Look at it:

– male vs. female

– scribal class and respectable vs. peasant class, and not even a well-liked peasant

– purposely comes at night to be secret vs. happens to be out at noon for privacy

– devout Pharisee who opens with doctrine vs. dubiously-practicing Samaritan whose questions are very concrete

– Jesus’ riposte is “you don’t understand these things” vs. “in this you have spoken truly”

I don’t know what these parallels mean, but they’re striking enough that I can easily believe they were deliberate, and do mean something.

4Perfective aspect is a form given to verbs to indicate when they are speaking about an action that is completed, but still pertinent. For an English example, imagine someone replying to Are you hungry? with I’ve eaten already: the cause of sating is in the past, but the fact of satiety is still relevant to the question. [Editor’s note: from this point forward, you can safely ignore the rest; you have been sated already with the pertinent information.] Now, English verbs are super wonky, and the way they get taught tends to mix up tense and aspect pretty badly. Most people, if they’ve learned “perfect” as a grammatical term at all, tend to think that it’s a specific kind of past tense; that’s not really the idea here, though. A verb’s aspect is really about how complete the action is. The usual basic categories here are: the incomplete or ongoing, often given the Latin-derived name imperfective; the finished, or perfective; and, in some languages, a third category for verbs with a weirder relationship to time—for example, proverbs that describe how things necessarily or habitually happen, rather than applying to a particular act.5 It might sound like perfective verbs would have to be past-tense anyway, since their action is completed, but that’s not actually true. In the sentence “I’ve eaten already,” we’re dealing with a present-tense verb, a present perfective. That’s why the helping verb “have” is in its present-tense form, instead of shifting to “had,” and also why a phrase like “I’m full” can be a synonym for “I’ve eaten”: the action (so to speak) of the verb is a present action. (If we do change the helping verb’s tense, making it “I’d eaten,” then we get a past perfective, also known as a pluperfect—but I won’t explain that now, for the sake of maintaining suspense.) This is why οἶδα, even though it’s a perfective verb, could be adopted as a different present-tense verb: technically, it already was present-tense.

5This kind of “third-type” aspect is referred to by linguists as gnomic, from γνώμη [gnōmē], a term originally meaning “opinion, thought, judgment,” and eventually applied to proverbs. (A number of English phrases, like “It never rains but it pours” or “Things fall apart,” exemplify the gnomic aspect.) Stative and aorist are also common “third aspect” categories; proto-Indo-European, the language ancestral to English, Greek, and Latin alike, had a stative aspect.

6The ordination lineage that could be traced back to Moses is believed by most Jews to have died out around the fifth century. Theodosius I, the sixth emperor after Constantine, illegalized s’mikhah, and the last person confirmed to possess this lineage seems to have been Gamaliel VI, who was also the last to hold the title of Nasi or “Prince,” accorded to the leader of the Sanhedrin; the title was abolished by Theodosius II on Gamaliel’s death in 425. (However, some reports suggest that this lineage did continue outside the Holy Land until at least the twelfth century, and a few people believe that is has never been extinguished.) Modern rabbis are appointed with a similar ritual, also called s’mikhah, but this is not generally held to be of the same nature as classical s’mikhah.

7The same is true today. If you’ve heard terms like Ashkenazi, Mizrahi, Sephardi, etc., these are the names of minhagim: cultural groups, originally geographic in origin, with specific ways of observing the Torah. If this just sounds like a confusing synonym for halakhah, that’s not quite the idea here: halakhah is the interpretation and application of the commandments themselves; a minhag is the cultural pattern of these rulings taken as a whole, plus strictly cultural practices that are not considered religious duties. (E.g., among Ashkenazis, latkes are a traditional Chanukkah food, but this is not at all the same sort of thing as keeping kosher!)

8When I say this book has done more for my faith than some of his theological works, that may be taken either as a backhanded insult, or as a statement that Studies in Words is a theological work in disguise. It is neither. This book, not although but because it is genuinely about the non-theological topic of linguistics, ranks alongside Screwtape in terms of the benefits I’ve reaped from it, many of them specifically from the chapter I’m now quoting.

9There’s a concealed irony in this. English has an extremely large vocabulary and is very accommodating of new words; Latin, by comparison, has a rather restrictive vocabulary, which occasionally caused serious misunderstandings between the Hellenistic East and the Latin West, particularly during the Christological debates of the fifth century. (One problem was that, etymologically, the Latin substantia was an obvious translation for the Greek ὑπόστασις [hüpostasis], but these words were used in completely different senses in Latin and Greek—which meant the Westerners sounded in Greek as if they were “confounding the Persons,” while the Easterners seemed in Latin to be “dividing the Substance.”) Nonetheless, of the four Greek terms discussed in this chapter (γῆ [gē], οἰκουμένη [oikoumenē], αἰών, and κόσμος [kosmos]), all received distinct Latin renderings (terra, orbis, sæculum, and mundus, respectively), so of course, all were collapsed into the one English term “world.”

10Brythons is, essentially, a pseudo-antiquated spelling of Britons; when used at all, it is typically to differentiate between the ancient British (a Celtic ethnicity akin to the modern Welsh) and the modern usage in which “Briton” means a citizen of the UK. Epirotes were, as everyone knows, natives of Epirus (roughly, modern Albania). Idumæans is a Latinized form of Edomites; the Herods were an Idumæan family (Idumæa as a whole had been converted to Judaism around a century before the birth Christ). Illyria, or Illyricum, was the Roman name for most of what we no longer call Yugoslavia. The Phoenicians existed in two main groupings: the one we’re used to thinking of, who lived on the coast of modern Lebanon in cities like Byblos and Tyre; and those descended from the Carthaginians, found in and around modern Tunisia, Malta, Sicily, and the south of Spain. The Carthaginian group were also called Afri (singular Afer [m.] or Afra [f.]), and it is from this name that the term “Africa” is thought to be derived. (The Latin Africa denoted, in modern terms, only Tunisia, the northeast of Algeria, and the west of the Libyan coast—Egypt, for example, was not by ancient standards “in Africa.”)