Series Table of Contents:

Introduction (what sacred/liturgical time is and why we have it)

The Canonical Hours (the Catholic “clock”)

The Former Holy Week (pagan antecedents of the week)

The Seventh Day (the Judaic week and the Sabbath)

⇒ The Revelation of the Octave (the Catholic week)

To Everything There Is a Season (Easter computus; fourfold interpretation of Scripture)

The Waxing of the Sun (the literal/meteorological year; the yearly allegory of the life of Christ)

The Waning of the Sun (the spiritual life through the lens of the year)

A Time to Get, and a Time to Keep (liturgical seasons in the Anglican Use)

Do — Re — Mi – Fa — So — La — Ti –

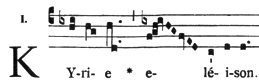

Square notation1 of the first phrase of the

Kyrie in the Missa Orbis Factor (“Mass of the

Maker of the World”), one of several

traditional plainchant2 forms of the Mass.

This post is pretty dependent on my last, so if you haven’t read that one yet, do go back and do that first. If you have, and you’re a musical person, then let us return to the analogy we instituted. (If not, it’s probably okay to skip down to after the indented bit.)

To jog your memory: The strings section of an orchestra is playing a tune in 7⁄8 time; the tune goes silent on every seventh beat, permitting a pipe organ’s droning do to be clearly heard, and the strings’ part only ever rises as high as the ti of its scale3; the lurching rhythm has a regularity, the tune has a resolution, but always in terms of what has been played before. Close to the end, a solo violin rises all the way to that ti, immediately before falling silent for the seventh beat.

Then come the final phrases of the piece—and as if out of nowhere, immediately, the pipe organ’s drone leaps up an octave, and at the same time, the solo violin comes back in on the do of the next octave up. As it continues, it becomes clear that these final bars are written in 8⁄8 time. This symbolizes Easter, and by extension, Sunday.

The period from Easter Sunday to the following Sunday inclusive is (coincidentally) known as “the Octave of Easter” in the Catholic Church: eight days in sequence that, for ritual purposes, are all a single Sunday. Moreover, besides the full rigor of Sinai being waived, the Sabbath is no longer observed on Saturday but on Sunday.

Given how much we built up the Sabbath in the last one, the gear-shift involved in moving it might feel both arbitrary and startling! Let’s look closer.

An Everlasting Covenant

In both Judaism and mainstream Christian theology,4 the narrative of the Bible is one of a succession of covenants. Genesis features divine covenants with Adam, Noah, and Abraham. Exodus introduces the central covenant of the Hebrew Bible, made with Moses; its most eminent sign is the Sabbath. At the Last Supper, Jesus claimed to institute a new covenant, which Christian theologians have creatively titled “the New Covenant.” The New Covenant is articulated in the ritual language of the Mosaic, but the former reworks the latter drastically, indeed metaphysically.

Now, the break here is not total. The Hebrew Bible has not stopped being divine revelation, and—despite what some Catholics, past and present, claim—the Jews have not lost their status as God’s chosen people5 (something St. Paul takes pains to emphasize in Romans 9-11). One thing that has changed is that it’s no longer necessary to become ethnically Jewish in order to participate in God’s covenant: Gentiles are now welcomed in as Gentiles.

But the break is also not merely a matter of “now boarding all ethnicities,” as it were. The promise of the Mosaic Covenant was, well, the Promised Land, for the children of Israel to dwell in. This makes sense if God’s people are literally a nation. The New Covenant promises a homeland of an altogether different kind: “the holy city, the New Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven as a bride adorned for her husband.” A new creation, an ontological change, is involved.

Baptismal font cover from the Church of the

Good Shepherd in Rosemont, PA. Photo by

Francis Helminski, used under a CC BY-SA

4.0 license (source).

Therefore, the Sabbath—which was built into the created order we have always known—is superseded by a new Sabbath: an eighth day; a fresh first day; its planet changes from Saturn, the slowest-moving of the seven, to the Sun, the brightest and swiftest of all. God rests on the Sabbath one more time, on Holy Saturday, and brings the new Sabbath with him when he rises and remakes the light.

The Christian Week

With all of that context, we start to grasp the Christian week! Since Easter inaugurates the new creation, or at least a foretaste of it, the new week is modeled partly on Holy Week. Two days—Sunday and Friday—assumed the most definite character of all, the days of the Resurrection and the Passion, respectively. As far as I can tell, these days’ symbolism is universal in Christian cultures.

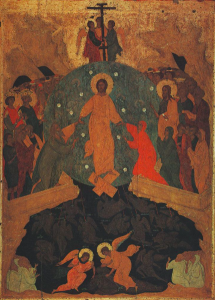

15th-c. ikon of the harrowing of hell from

Ferapontov Monastery in Russia. The figures

Christ is lifting his his left and right hands

are Adam and Eve.

The other five days are a little less strongly defined, their significance less consistent between one part of the Church and another, though some common threads persist.

- Wednesday probably has the next-most constant meaning: as early as the Didache (a second- or possibly even first-century work), it is treated as a day of fasting alongside Friday.6 One explanation I’ve heard for this draws on the timeline of Holy Week: Judas approached the Sanhedrin to arrange the betrayal of Jesus on that week’s Wednesday. Probably. (Gospel chronology is tough.)

- Thursday is strongly associated with the Blessed Sacrament, since Jesus instituted the Eucharist on Maundy Thursday.

- Saturday is associated with the Mother of God; why, I’m not sure. Perhaps, with Sunday as our Lord’s day, it was felt to be fitting to turn “Sunday eve” into “our Lady’s day”; or perhaps her stature as the “hinge” between the Jewish people and the Church (as discussed in note b of this post on the “Daughter of Zion” in Revelation 12) led to honoring her on the former Sabbath.

- Monday and Tuesday are the problem children of the bunch. I’ve seen them assigned to St. Joseph, St. John the Baptist, the Apostles in general, the souls of the departed, and the holy angels (some of which I’ve also seen pinned to Wednesday); I think I’ve also seen Monday assigned to the Holy Ghost, though I don’t recall where. That’s five or six distinct meanings for two days of the week. In my opinion, five or six is more than two, which is not convenient.

Diagrams in a Carolingian manuscript showing

the division of the day into hours (left) and of

the week into days (right).

If you’re particularly looking to have themes for Monday and Tuesday, I’d be inclined to assign Monday to the holy angels and Tuesday to the Baptist and the Apostles. Here’s why.

In the creation account, Monday is associated with the waters, and the division of the upper from the lower by the firmament; it’s also the only day of which God doesn’t say that “it was good.” In Holy Week, Monday is “Fig Monday,” the day when the blasting of the fig tree is commemorated. Both of these seem to me to point to an association between Mondays and falls—division by the firmament even kind of suggests the angels. Even the association of Monday with the Moon, the only one of the classical planets that has a visible “dark side,” fits with this. Obviously we don’t honor the angels who fell, but I think it makes sense of the associations to use Monday to honor the angels who stood firm.

As for Tuesday, of the six possible themes I’d found for these two days, I notice that four of them—the Holy Ghost, the holy angels, St. John the Baptist, and the Apostles—have associations with prophecy in the Biblical sense, i.e. bearing a message from God to his people or to mankind in general. In that light, I think it makes sense to honor the Baptist and the Apostles together, as the herald and viceroys of the King. (And if we also wanted to keep the themes of praying for the souls of the departed and honoring St. Joseph, well, I see no reason we couldn’t add those to Wednesday and Saturday.)

I’ve summarized all the info I’ve touched on below, in a handy little chart of the Christian week that I very much hope is legible after the trouble it’s given me!7 For fun, I’ve also thrown in the seven virtues, according to which classical planet each one is associated with (derived partly from the layout of Dante’s Paradiso). If you liked, you might pray specially for an increase in that virtue on each day of the week.

The Enemy

When discussing the usefulness of the canonical hours, I identified them as useful against accidie—the discouraging distaste that comes over us and tends above all to sap our hope, love, and courage (the virtues that most impel us forward). What then is the Christian week designed to fight?

I don’t know that this exhausts its purpose by any means; but I can quite bluntly identify one temptation it addresses: avarice. As with the old Sabbath, so with the new, the practice of simply taking one day per week and refusing it to secular use, especially our employers’ use, is in itself a testimony that we cannot and do not serve both God and mammon.

I’m of the opinion that we need that testimony particularly badly in this day and age, which is trying with all its might to unlearn the lesson offered to it by 2020’s quarantines: namely, that “unskilled” laborers actually do some of the most essential work in our economy, and that it is overwhelmingly (albeit not entirely) the managerial class that sponges off them, not the other way round. That might seem like an essentially political point. It is; but that doesn’t necessarily mean it isn’t a theological point too. Being a Catholic has political consequences sometimes, usually indirectly but on rare occasions quite directly (e.g., we may not join Freemasonry or the Communist Party). I might be mistaken about this, but it is my opinion that our thoroughgoing embrace of capitalism, an economic system the Church has authoritatively and explicitly condemned as unjust for well over a hundred years now, is a primary driver of the corruption of the faith we have seen over the last several decades. I’d even argue that it has contributed to the abuse crisis, not least by training bishops to think and behave like managers, which is a fair enough quality in a manager but is a disgusting trait in a father.

Driving of the Merchants From the Temple

(ca. 1580), by Ippolito Scarsellino—speaking

of Holy Week.

Alrighty! Now we’ve got this bit done, we can turn from the weekly to the annual cycle.

Footnotes

1Square notes are also known as neumes. They are the immediate ancestor of modern five-line musical notation, and are therefore similar in some respects, like the flat sign. They also change or reverse certain five-line conventions: for instance, square notes never denote absolute pitch, as five-line notation does—only relative pitch. This allows any choir to sing the same tune in a comfortable range.

2Plainchant is the musical genre to which the more famous Gregorian chant belongs. Technically, “Gregorian” only means the Roman type of chant, named after Pope St. Gregory I; there are other kinds of plainchant, such as Ambrosian (used in Milan) or Mozarabic (once used in Portugal and Spain). All plainchant is unaccompanied and monophonic. The Missa Orbis Factor, a setting of the Mass in Gregorian chant in the strict sense, features a fairly long, ornate Kyrie.

3Of course I didn’t think of a clever reference for what key it could be in. Who am I, Aleksandr Skriabin?

4It is important to note that, historically and statistically speaking, Dispensationalism—although still popular in much of the US, mainly in Baptist, charismatic, and non-denominational circles—lies well outside the Christian theological mainstream.

5St. Paul takes some pains to make this clear in Romans 9-11. He does say that the Jews have, so to speak, lost the exclusivity of their access to God; nonetheless, “God hath not cast away his people which he foreknew … For the gifts and calling of God are without repentance.”

6It may be worth mentioning for clarity’s sake, this doesn’t necessarily mean the custom of treating Wednesdays this way was universal among Christians when the Didache was written; it just means the custom was known to at least some Christians at the time. The document’s explanation is less than helpful: Apparently “the hypocrites” (thought to be a reference to the Jews) “fast on Mondays and Thursdays; therefore you are to fast on Wednesdays and Fridays”—no idea why Tuesday got a pass.

7If, as I grouchily suspect, it is not: the categories (from left to right) are: Planet; Day; Creation Week; Holy Week; Theme; Traditions; and Virtue.

The first (yellow) row is: the Sun; Sunday; light; Easter Sunday; the Resurrection; attending the liturgy and observing the new Sabbath; and wisdom.

The second (grey) row is: the Moon; Monday; the upper and nether waters; Fig Monday; the holy angels; none; and faith.

The third (red) row is: Mars; Tuesday; the dry land and the plants; Temple Tuesday; St. John the Baptist and the Apostles; none; and courage.

The fourth (brown) row is: Mercury; Wednesday; the luminaries; Spy Wednesday; repentance, and perhaps also the souls of the departed; penance of some kind (often fasting); and hope.

The fifth (blue) row is: Jupiter; Thursday; birds and fish; Maundy Thursday; the Blessed Sacrament; Eucharistic Adoration; and justice.

The sixth (blue-green) row is: Venus; Friday; the animals and the Adam; Good Friday; the Passion; abstinence from meat and fasting; and charity.

And the seventh (orange) row is: Saturn; Saturday; nothing (this being the old Sabbath); Holy Saturday; the Mother of God, and perhaps also St. Joseph; none (or perhaps fasting, since it’s “Sunday eve”); and temperance.