Another Lengthy One

This one is long not because it’s multiple lessons together, but because the lesson we have cut St. Paul’s … whole sermon. Which, I get it, it’s long, and we do get a lot of readings from the Pauline epistles all year—but it kinda bums me out, because St. Paul doing a homily sounds rather different from St. Paul writing a letter. The next will probably be lengthy too, for similar reasons.

As before, I’m aiming for limited, more in-depth notes. (A few names differ in my version: I think the only conspicuous differences are Bar-Nevua’ for Barnabas, Kana’an for Canaan, and Moshe for Moses—in all cases, as usual, I’m trying to more closely approximate the original Hebrew or Aramaic in English.) And here we go!

Acts 13:14, 15-42, 43-52, RSV-CE

They passed on from Perga and came to Antioch of Pisidia.1 And on the sabbath day they went into the synagogue and sat down. After the reading of the law and the prophets, the rulers of the synagogue sent to them, saying, “Brethren, if you have any word of exhortation for the people, say it.” So Paul stood up, and motioning with his hand said:

“Men of Israel, and you that fear God, listen. The God of this people Israel chose our fathers and made the people great during their stay in the land of Egypt, and with uplifted arm he led them out of it. And for about forty years he bore with them in the wilderness. And when he had destroyed seven nations in the land of Canaan, he gave them their land as an inheritance, for about four hundred and fifty years. And after that he gave them judges until Samuel the prophet. Then they asked for a king; and God gave them Saul the son of Kish, a man of the tribe of Benjamin, for forty years. And when he had removed him, he raised up David to be their king; of whom he testified and said, ‘I have found in David the son of Jesse a man after my heart, who will do all my will.’ Of this man’s posterity God has brought to Israel a Savior, Jesus, as he promised. Before his coming John had preached a baptism of repentance to all the people of Israel. And as John was finishing his course, he said, ‘What do you suppose that I am? I am not he. No, but after me one is coming, the sandals of whose feet I am not worthy to untie.’

“Brethren, sons of the family of Abraham, and those among you that fear God, to us has been sent the message of this salvation. For those who live in Jerusalem and their rulers, because they did not recognize him nor understand the utterances of the prophets which are read every sabbath, fulfilled these by condemning him. Though they could charge him with nothing deserving death, yet they asked Pilate to have him killed. And when they had fulfilled all that was written of him, they took him down from the tree, and laid him in a tomb. But God raised him from the dead; and for many days he appeared to those who came up with him from Galilee to Jerusalem, who are now his witnesses to the people. And we bring you the good news that what God promised to the fathers, this he has fulfilled to us their children by raising Jesus; as also it is written in the second psalm,

‘Thou art my Son,

today I have begotten thee.’

And as for the fact that he raised him from the dead, no more to return to corruption, he spoke in this way,

‘I will give you the holy and sure blessings of David.’

Therefore he says also in another psalm,

‘Thou wilt not let thy Holy One see corruption.’

For David, after he had served the counsel of God in his own generation, fell asleep, and was laid with his fathers, and saw corruption; but he whom God raised up saw no corruption. Let it be known to you therefore, brethren, that through this man forgiveness of sins is proclaimed to you, and by him every one that believes is freed from everything from which you could not be freed by the law of Moses. Beware, therefore, lest there come upon you what is said in the prophets:

‘Behold, you scoffers, and wonder, and perish;

for I do a deed in your days,

a deed you will never believe, if one declares it to you.’”

As they went out, the people begged that these things might be told them the next sabbath. And when the meeting of the synagogue broke up, many Jews and devout converts to Judaism followed Paul and Barnabas, who spoke to them and urged them to continue in the grace of God.

The next sabbath almost the whole city gathered together to hear the word of God. But when the Jews saw the multitudes, they were filled with jealousy, and contradicted what was spoken by Paul, and reviled him. And Paul and Barnabas spoke out boldly, saying, “It was necessary that the word of God should be spoken first to you. Since you thrust it from you, and judge yourselves unworthy of eternal life, behold, we turn to the Gentiles. For so the Lord has commanded us, saying,

‘I have set you to be a light for the Gentiles,

that you may bring salvation to the uttermost parts of the earth.’”

And when the Gentiles heard this, they were glad and glorified the word of God; and as many as were ordained to eternal life believed. And the word of the Lord spread throughout all the region. But the Jews incited the devout women of high standing and the leading men of the city, and stirred up persecution against Paul and Barnabas, and drove them out of their district. But they shook off the dust from their feet against them, and went to Iconium. And the disciples were filled with joy and with the Holy Spirit.

Acts 13:14, 15-42, 43-52, my translation

![]()

The red dot is Antioch; the lines connect it to

Perga (south-ish) and Iconium (southeast).

Modified from a map by Caliniuc, used

under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

Coming through from Perga, they arrived in Antioch-in-Pisidia,1 and they entered the assembly on the sabbath day and sat down. After the reading of the Law and the Prophets, the assembly-elders sent word to them: “Men and brethren, if there is among you any word of encouragement for the people, say it.”

Paul stood up and waved his hand, and said: “Men, Israelites and fearers of God, listen. The God of this people Israel selected our fathers, and he lifted up this people in their pilgrimage in the land of Egypt, and by his lofty arm he led them forth from there; and so he put up with them forty years’ time in the desert, and, having taken out seven nations in the land of Kana’an, he allotted them the land, and so four hundred and fifty years were finished. After these things, he also gave them judges until Samuel the Prophet. At that point, they asked for a king, and God gave to them Saul, son of Kish, a man of the tribe of Benjamin, for forty years; and after him, he roused David to kingship for them, about whom he also said, bearing witness: ‘Look—David, the son of Jesse, a man according to my heart, who will do everything I will.’

“Of him, from his seed, according to his promise, God brought to Israel a savior, Jesus; before his entry, John proclaimed his person beforehand with a washing of change of heart for the whole people of Israel. As John fulfilled his course, he said: ‘Do you suppose I am anyone? I am not; but see, there comes after me one whose sandals I am not worthy to loosen.’

“Men and brethren, sons of the clan of Abraham and those among you who fear God: by us, this word of salvation has been sent out. For those living in Jerusalem and their rulers were ignorant of this, though the voices of the Prophets are read every sabbath—judging, they fulfilled them, and finding no capital cause, they asked Pilate to put him to death; so when everything written about him was ended, they took him off the tree and put him into a memorial. But God roused him from the dead; he was seen over many days by those who went up with him from the Galilee to Jerusalem, which are now his witnesses before the people. We too tell you this good news promised to the fathers, because God has fulfilled it to us, their children, by raising up Jesus, as it is also written in the second psalm: ‘You are my son, today I have begotten you.’ Because he raised him up from the dead, never to return to rot, just as it has said: ‘I give to you all the holy and faithful things of David.’ For which reason it also says in another place, ‘You will not give your holy one over to rot.’ Now, David served God’s will in his own generation, fell asleep, and was placed with his fathers, and rotted; but him whom God roused did not rot.

“Be it known to you, then, men and brethren, that by this man, remission of sins is declared, and for everything about which you could not be justified by Moshe in the Law, everyone who believes in this man shall be justified. Look, then, do not be overtaken by what is spoken of in the Prophets: ‘See, O scornful ones, and be astonished and disappear, because I am doing a deed in these your days, a deed which you will not believe in if anyone explains it to you.'”

As they went out, they called for them to tell them about these things the next sabbath. And when the assembly was released, many of the Jews and the devout converts followed Paul and Bar-Nevua’, who talked with them and persuaded them that they should remain in the grace of God. Come the next sabbath, nearly the whole city gathered to hear the word of the Lord.

Seeing the crowds, the Jews were filled with fervor and contradicted what Paul said, slandering him. And so both Paul and Bar-Nevua’, speaking frankly, said: “It was necessary that the word of God be spoken first to you; now that you reject it and do not judge yourselves worthy of eternal life, see, we will turn to the nations; for thus the Lord charged us: ‘I have placed you to be a light of nations for salvation to the end of the earth.'” Hearing this, “the nations” rejoiced and glorified the word of the Lord, and those who were appointed to eternal life believed; the word of the Lord was borne through the whole region.

Then the Jews provoked the reputable devout women and the first men of the city, and roused up a persecution against Paul and Bar-Nevua’, and threw them out of their borders. So they shook the dust off their feet against them, and went to Iconium, and the students were filled with joy and a holy spirit.

St. Barnabas, from an altarpiece (c. 1490)

by Sandro Boticelli.

Textual Notes

a. you that fear God | fearers of God (οἱ φοβούμενοι τὸν θεόν [hoi foboumenoi ton theon]): Here, we have a category of people who don’t fit quite neatly into the Jewish-Gentile distinction; or rather, they do—they are Gentiles—but they exhibit an interest in Judaism that is atypical of Gentiles. They are most frequently called God-fearers, and they were key to the spread of Christianity in its early centuries.

Exactly when or why the God-fearers came into existence does not appear to be known; the story of Naaman the Syrian in II Kings 5 suggests there may have been God-fearers as far back as the pre-Exilic era, at least in the Near East (which for these purposes does not include Anatolia). The original nationality of the Herod family, the Idumeans—in earlier language, the Edomites—were comparatively recent converts to Judaism in the first century BC, and may have been God-fearers before that; the same could be true of the Magi described in Matthew 2, who would almost certainly have been in contact with the Parthian-ruled Iraqi Jews of Babylonia.

Talmud Readers (c. 1930s?), by Adolf Behrman.

However, in this text, we are dealing not with Semitic but Hellenistic God-fearers. These arose in the post-Alexandrian period, perhaps from as early as the third century BC, certainly by the first CE. As the Jews increasingly made settlements around the Mediterranean—in places like Cilicia, Cyrenaica, Egypt, Galatia, Ionia, Osroene, Rome, and Thessaly—freedmen and women seem to have been particularly interested by Judaism. It also attracted some attention from ancient philosophers, many of whom had moved in the direction of transcendental monotheism.2 But the interest was what you’d call “mixed.”

Some aspects of Judaism struck Gentiles as disgusting, anti-social, or ridiculous, like circumcision and the rules of kosher—the latter of which prevented the Jews from buying meat at any non-Jewish market or butcher’s (not only because it would likely still have blood in it, to say nothing of possible cross-contact with non-kosher meats like pork, but because market meat was from animals sacrificed to pagan deities). This Jewish aloof-ness appears to have annoyed Greeks especially; perhaps it was because they hadn’t been looked down on by anybody in five centuries,3 and didn’t know how else to deal with it. Indeed, it’s arguable—especially in light of the conflict between the Maccabees and the Seleucids4—that we see the world’s first identifiable anti-Semitism among the Greeks. But, obviously, not all Greeks felt that way, and those who did weren’t necessarily immune to the fascination of Judaism anyway.5

Furthermore, the Romans had a somewhat higher view of the Jews than the Greeks did. Admittedly, they found Judea annoying as all hell, and they were as baffled as most polytheists by the Jewish taboo against onboarding their neighbors’ deities. However, the Romans were an intensely family-centric culture—think of the all-important Vestal Virgins, and then recall that Vesta was goddess of the hearth—and placed immense value on the mōs majōrum or “way of the elders” as an essential component in being Roman. So the fact that the Jews were keeping customs handed down to them by their ancestors was by itself enough to earn their respect. They admired the Jewish resistance to divorce6 for the same reason; and they appreciated the Jews’ emphasis on scholarship, which was closely identified with adult masculinity in Roman culture (far more so than athletic or martial accomplishments—check out this video essay from the excellent channel The Historian’s Craft for a little more on Rome’s conception of manliness).

A mezuzah7; its positioning at an angle instead

of vertically suggests this is likely at an

Ashkenazi8 residence. Photo by Tomi Valny,

used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

Still, whether among Romans or Greeks, full conversion was rare. Besides the hefty “price tags” of circumcision and observing the Torah, abandoning one’s traditional gods in favor of a foreign one is the sort of thing many families, and indeed societies, don’t greatly like. There were converts—probably, then as now, often people who converted for familial unity with a spouse—but it wasn’t commonplace. God-fearers, rather than go the whole way, would live somewhere in between: They might study the Torah, but only in the Greek version from Alexandria; they might commemorate major holidays, but not keep the sabbath strictly; they might refrain from pork, but still buy meat from the market.

People in this position—interested in, perhaps even captivated by, the God of Israel, yet reluctant to break formally and completely with “their people and their father’s house”—were to be found in basically any city with a synagogue. In many cases, their faith was ripe enough to fall right off the tree as soon as they heard St. Paul!

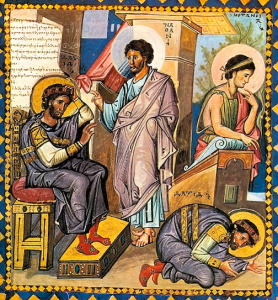

Byzantine miniature (late 11th c.) of SS. Peter

and Paul and the Four Evangelists.

b. to us | by us (ἡμῖν [hēmin]): Here, I have made an interpretive choice—something I try not to do as a rule, and strive to make very clear when I have done it. (I have some faint hope that the fact “by” has a few distinct meanings in English cushions this a bit, too.) In other passages, e.g. II Corinthians 5:14-6:2, Paul emphasizes that the Apostles are the means-by-which the Word and all his functions are brought forth to the rest of the world. This, together with the sense of the rest of the sentence, makes by us seem more logical to me, although ἡμῖν here does not have the preposition it would typically take (ὑπό [hüpo]) to specify that meaning.

c. nothing deserving death | no capital cause (μηδεμίαν αἰτίαν θανάτου [mēdemian aitian thanatou]): Literally, “no cause of death.” By this time, in late Second-Temple Judaism, it was actually fairly difficult to put someone to death according to the rabbinic rules for interpreting the Torah (and since the Sadducees, even when they held key leadership positions in the Sanhedrin, were more or less always in the minority, it was rabbinic—that is, Pharisaic—rules that tended to prevail).

d. corruption | rot (διαφθοράν [diafthoran]): The English word corruption now carries a primarily abstract or moral meaning. The word still has a certain energy, perhaps thanks to its audial and visual similarity to phrases like rip up or throw up; interestingly, it also retains some amount of specificity, pointing mainly to willingness to accept bribes. (It differs in these ways from words like wickedness or iniquity, both of which, and especially the latter, have lost a great deal of the power they had as recently as the early twentieth century, and neither of which have any very particular vice in their crosshairs.) The Greek originates in the verb φθείρω [ftheirō], which meant things like “to waste, spoil, decompose”; it was probably derived from φθίω [fthiō], “to waste away,” which is the root of the old-fashioned term phthisis for “consumption” (i.e., tuberculosis).

The Altar of the Crucifixion in the Church of

the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem. Photo by

Wikimedia contributor Ondřej Žváček,

used under a CC BY 2.5 license (source).

e. by him every one that believes is freed from everything from which you could not be freed by the law of Moses | for everything about which you could not be justified by Moshe in the Law, everyone who believes in this man shall be justified (ἀπὸ πάντων ὧν οὐκ ἠδυνήθητε ἐν νόμῳ Μωϋσέως δικαιωθῆναι ἐν τούτῳ πᾶς ὁ πιστεύων δικαιοῦται [apo pantōn hōn ouk ēdünēthēte en nomō Mōüseōs dikaiōthēnai en toutō pas ho pisteuōn dikaoutai]): Here we touch upon one of the sparks of the Protestant Reformation; from another point of view, we run into one of the most typical misinterpretations of Judaism among Christians. The two ideas are rather tied together. Permit me to attempt some disentangling.

It’s common for Christians, especially in the US, to assume that Judaism is “Christianity minus Jesus” (which is already an odd idea, but never mind). It’s therefore common to suppose that Judaism is trying to give an answer to the question, “How can I be put right with God so that I go to heaven when I die?”, and common likewise to assume the Judaic answer must be “By doing good works, which the Torah is our guide to.”

Judaism isn’t the only target of such assumptions. Many American and/or Protestant Christians believe, sometimes as an article of religious doctrine, that this question is the religious question haunting everyone (whether they “admit it” or not). More specific still, it’s often claimed that all religions other than Protestant Christianity give the false answer “Good works.” Trying to earn a place in heaven is conceived not merely as being an error but the error, the fundamental, universal sin humans are prone to, under endless disguises. A number of superficial observations about Judaism and Jewish culture—like the trope of “Jewish guilt,” or the meticulous care with which many practicing Jews treat the sabbath—appear at a glance to confirm this, and a very large fraction of Christians look no further.

Aškenaška Synagogue in Sarajevo, Bosnia.

Photo by Michał Huniewicz, used under

a CC BY 2.0 license (source).

Suffice it to say that most religions, if approached on their own terms and not as increasingly deformed versions of American Protestantism, are in fact not addressed to the same questions as Billy Graham. (Which isn’t a knock on Billy Graham, either! It’d be weird if he weren’t addressing his part of the world as he found it—but it was after all only a part.)

Dealing with guilt—both in the moral sense of “being deserving of blame before God,” and in the psychological sense of “feeling bad about yourself due to things you’ve done or failed to do”—is not alien to Judaism, nor was it at the time; however, the theological style of Christianity has developed independently of Judaism in the ensuing twenty centuries. This is especially true of Latin Christianity, which encompasses both Catholicism and Protestantism. In particular, divine forgiveness, and how it is given and gotten, are treated by Latin Christians as basic to our faith. There are and have been debates over what exactly baptism confers, or whether the Church has the authority to absolve sins and, if so, how far that authority extends; such controversies are exemplified in the Reformations, but go at least as far back as the second century. The debates are so intense and involved because this topic is central for us.

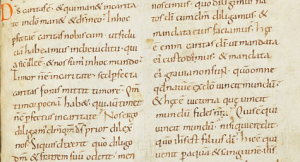

The Reproach of Nathan and the Penance

of King David (10th c.), from the Byzantine-

made Paris Psalter.

We tend to project that centrality backward onto the Levitical sacrificial system,9 and assume that all or most sacrifices were to obtain pardon for sins. (The book of Hebrews may appear, on a casual reading, to confirm this assumption; I don’t believe it does so in truth, but we can’t stop for a full analysis.) But this isn’t really how the sacrificial system worked. The Levitical system had four basic varieties of sacrifice:

- חַטָּאת [ḥaṭâ’th], meaning “sin” or “cleansing”

- אָשָׁם [‘âshâm], meaning “guilt” or “trespass”

- עוֹלָה [ ṛawlâh], meaning “burnt” or “ascending” (often transliterated olah)

- שְׁלָמִים [shlâmîm], meaning “peace” (literally “peaces”)

These latter two kinds were equally prevalent with the first two in the Temple system, if not more so. The burnt offering was the form of the תָמִיד [thâmîdh], the daily offering that was to be made “day by day continually” (Exodus 29:38-46), no matter what else was also being offered. Thanksgiving offerings and votives were varieties of peace offering, and could be made of free will at any time. The first two were normally offered at specified times (some of which are described in Leviticus 4:1-6:7, with accompanying procedures), and apt to be communal or national affairs—for example, holidays like Yom Kippur.

And the lesson of sacrifices in general was not focused on forgiveness of sins alone. That was one thing a sacrifice could be made for, but it was, so to speak, occasional; the essential purpose of the templar system was the turning of the mind to God, whether that needed to be accompanied by repenting of something or not. I think it’s significant that, even though “Christ was made a sacrifice for sins” is a candidate for “idea explicitly repeated by the most books in the New Testament,” even so, his Body and Blood in the Sacrament are designated something else—not the Hamartia or the Parabasis,10 but the Eucharistia, the thanksgiving offering.

f. devout converts to Judaism | devout converts (τῶν σεβομένων προσηλύτων [tōn sebomenōn prosēlütōn]): These are not quite the same as the God-fearers from note a. God-fearers, though they practiced elements of Judaism, remained Gentiles; converts did go through the process of becoming Jews, including circumcision (for men), immersion in a mikveh, and swearing to live according to the Torah. The Greek προσήλυτος [prosēlütos], meaning “foreigner” (or perhaps, a little more kindly, “sojourner, resident alien”), may be a conventional translation of the Hebrew גֵּר [gêr] “stranger,” which is still used to refer to Gentile converts to Judaism.

Naomi Entreats Ruth and Orpah to Return

to Moab (1795), by William Blake.

g. the Gentiles | “the nations” (τὰ ἔθνη [ta ethnē]): I went with “the nations” here because (a) it is more literal, and (b) it is the same word back up in verse 19, when he was talking about the Canaanites expelled in Israel’s favor. By using “nations” in one place and “Gentiles” in another, the thematic resonance between the beginning and end of St. Paul’s homily is lost in the RSV. And that’s a real shame, because it’s kind of the point of the book of Acts.

We begin in Acts 1 with a hundred and twenty disciples, all from among Jesus’ close friends and family. He ascends; the glory is withdrawn into itself; but, though the imagery sounds like the removal of man from Eden, the atmosphere of the text is quite different—more like the creation narrative, where “the earth was without form, and void,” but “the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.” It may, or may not, be a coincidence that there were so many Maries in the cenacle. A possible meaning of the Hebrew name מִרְיָם [Miryâm], from which Mary, Miriam, Marie, etc., are derived, is “bitter sea,” i.e. salt rather than fresh water. The Holy Ghost brooding over the Maries of the proto-Church until chapter 2, when light in the form of tongues of fire bursts over them, is quite an image. St. Peter’s sermon in chapter 2 brings the beginning and the end together, and speaks of the Diaspora, who are also heirs of the promise—but of course we know that this is going to overflow even those borders. Chapters 3 through 5 indicate the division among the Jews, continuing from Jesus’ own in-person ministry: some will accept the word, some will not.

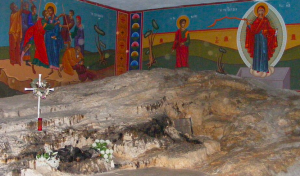

Grotto of the stoning of St. Stephen, beneath

the Greek Orthodox church dedicated to him

in the Kidron Valley, between the citadel of

Jerusalem and the Mount of Olives.

Chapters 6 through 8 show the promise and the division colliding, and exploding. The expansion of the gospel among the Hellenists leads to internal division and so to the creation of the diaconate, to which St. Stephen is elevated, as is one Nicolaus, noted to be a Gentile convert to Judaism and originally from Antioch, both moments of foreshadowing. Stephen’s work of reconciliation is successful, and this, like the miracles of Peter from the previous chapter, helps the gospel advance from Jerusalem into the wider Judean orbit. Stephen’s new position also draws him into debates with anti-Nazarene Jews; invited to explain himself to the Sanhedrin, he gives a complete sketch of redemptive history—not unlike the one St. Paul gives here—which becomes the proximate cause of his Christlike martyrdom. (We also find Paul’s first appearance in the narrative here, a touch of comic irony.)

This recapitulation of Jesus’ Passion results in a recapitulation of Pentecost, one in which the next step of Jesus’ commission from back in chapter 1 is also reached, as first the gospel and then the indwelling of the Holy Ghost come to Samaria. With the Samaritans, and the nod to Ethiopian Jewry in the eunuch, we’ve come to the very cusp of those anyone was willing to regard as Jews … and then St. Paul himself converts in chapter 9. And then the actual Gentile mission opens in chapter 10.

Vision of Cornelius the Centurion (1664), by

Gerbrand van den Eeckhout, a student of

Rembrandt’s.

The thing is, all of this is reversing the progression of Israelite history given in the Torah and the Former Prophets (Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings). There, it’s all a process of winnowing down. In Genesis 11, as in Acts 2, there is a miracle of language, but one that divides instead of harmonizing. After that we have the stories of the Patriarchs; they worship the one true God, but little if any mention is made at this stage of eliminating idolatry. After the deliverance from Egypt, then those who will and will not receive God’s Law begin to be revealed. More and more, the distinction between Hebrew and Gentile is impressed upon them: They are separated from their kinsfolk of Moab and Midian and Edom; the Davidic kingdom itself is split between Israel and Judah; in the book of Ezra (which continues the interests and genre of the Former Prophets), the original division between Samaria and Judea is seen coming into being.

And Paul’s sermon is reproducing this. “The nations,” the very people who were driven out at the beginning, become the main inhabitants of Antioch to receive God’s promise by the end. Or, put in the words of Hosea that St. Paul himself uses in Romans, “it shall come to pass, that in the place where it was said unto them, ‘Ye are not my people,’ there it shall be said unto them, ‘Ye are the sons of the living God.'”

Ikon of the Fathers of the First Council

of Nicæa, holding a copy of the Creed.

h. the Holy Spirit | a holy spirit (πνεύματος ἁγίου [pneumatos hagiou]): As in note b, this is something of an interpretive choice. Ancient scripts did not make use of case distinction in letters: They wrote either in majuscule, consistently the earlier form of a given script, with characters that fit neatly between a single pair of parallel lines—think of the letters P A B; or they wrote in minuscule, a book-hand developed out of majuscule letters, with some characters marked by ascenders or descenders that fit within four parallel lines—now think of the letters p a b. The majuscule and minuscule forms of the Roman alphabet would later become the basis of our upper- and lower-case writing, but “later” here means “primarily after the introduction of the printing press.” Most manuscripts of the New Testament we use to establish its text are in minuscule, though some are majuscules.

As a result, in the Greek, there is no visual difference between the holy spirit and the Holy Spirit. The translator must rely on context and other grammatical clues to decide whether the words mean

i. the Holy Spirit,

ii. not that, or

iii. maybe but not necessarily that

—and, if they go with option iii like I did, they must then decide how to convey the ambiguity, which I’m not at all sure I’ve done well, to be honest!

The textual reason I preferred option iii is that in this case, the Greek lacks the definite article. Now, that is not decisive; the Greek article doesn’t play by all the same rules as the English—for instance, it can occur before names, and sometimes it fills in for demonstrative, relative, indefinite, or personal pronouns—so I’d hate for you to come away with the impression that the RSV (or most translations) are pulling a fast one on their readers by inserting it and capitalizing “the Holy Spirit.”11 However, I personally think that the text is slightly more likely to have a more generic, less elevated meaning here: a holy disposition, mood, or cast of mind, things which are all good and may be His gift but are not, themselves, the Third Person of the Trinity.

I certainly do think the Holy Ghost was the ultimate source of this blessing, whether St. Luke is talking about the Holy Ghost in this verse or not. But I view my job as a translator to be offering readers, as closely as I’m able, not what the text means but what it says (with all of the adjustment that a translation into English calls for—a ticklish balance to strike). I think option i is a valid and indeed a likely interpretation, but it does seem to me to be an interpretation; and I view the proper place for interpretations as being here, in accompanying notes, not presented as if it were the text.

The Chair of Peter (1666), by Gian Lorenzo

Bernini. Photo by Wikimedia contributor

Dnalor1, used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license

(source).

Footnotes

1Like Alexander the Great, his general Seleucus Nicator (or “Whitey the Winner”) also named a great many cities, and also gave them all the same name. (You’ll notice that Alexander and his heirs fall after what is generally regarded as “Classical Greece” in the strict sense; the creative energy of the Greeks seems to have lagged a bit.) However, instead of naming them after himself, Seleucus named them after either his father or his son, both of whom were named Antiochus. The first Antioch lay on the Syrian coast; it is now in the south of Turkey, and known as Antakya.

2I use the phrase transcendental monotheism to distinguish what these philosophers were interested in from (a) national henotheism (acknowledging other gods while worshiping only one), (b) Abrahamic monotheism (at the time, Judaism), and (c) syncretistic monotheism, which became fashionable in the second and third centuries throughout the Roman Empire. This “transcendental monotheism” was probably one influence that formed (c); but, unlike syncretism, it tended to view mythology derisively.

3I.e., when the Persian Empire tried to conquer Greece in the early fifth century BC. A century and a half later, Alexander the Great swung through and showed them what was what; true, his empire promptly broke in pieces on his death, but all the pieces were still Greek-ish. The Romans did conquer the Greeks a few hundred years after that, in fits and starts, but, even when they enslaved them, the Romans didn’t look down on the Greeks as such. Greek culture was widely respected in Rome, even if a few Latin hard-liners thought it was prissy. (The relation between Roman and Greek culture in the first century wasn’t unlike that between English and French culture in the fourteenth, or indeed, now.)

4The Seleucid Empire was one of the successor states to Alexander’s: At its greatest extent, it encompassed modern Lebanon, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Syria, and Turkmenistan, along with parts of Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, and Turkey; in the second century BC, it annexed the previously Ptolemaic Egyptian province of Judea. (Unluckily for them, they did not also annex the Ptolemies’ “ignore what happens in Judea at all times” approach to governing it.) The Seleucid dynasty was a Syro-Greek blend with an accent on the “-Greek,” which is why, when meddling with the Temple sounded like a fun idea that would end well, they re-assigned its chief altar to Zeus and started sacrificing pigs on it. This is part of why Chanukkah (חֲנֻכָּה [Ḥànûkâh], “dedication”) was still a big deal in the first century, almost two hundred years later—it even puts in a cameo in the New Testament (John 10:22).

5Honestly, this they should have seen coming; different god, but thematically, “I hate this, show me more” is basically the theme of The Bacchæ.

6Divorce was (and is) permitted in Judaism, as it was in Rome. However, then as now, devout Jews generally disliked divorce and avoided it when possible, and there were restrictions associated with it; Levites, for instance, had to be married to women who were not only of pure Jewish descent, but virgins (which meant among other things that they could not be married to divorcées). Perhaps the only time in the Gospels where Jesus sides with the rigorist school of Shammai over the lenient school of Hillel (strains within Pharisaic Judaism) is on the question of divorce: Hillel allowed it for downright trivial causes, while Shammai recognized adultery alone as grounds for divorce.

7A mezuzah (Heb. “doorpost, door-jamb”—roughly pronounced meh-ZUZZ-uh) is a tiny scroll with a few lines from the Torah written on it by a qualified scribe. Observant Jews place a mezuzah on every doorway into a building; this is held to partly fulfill the command given in Deuteronomy, twice.

8Ashkenazi Jews are Jews with an ethnic background in the center of Europe—central on a north-south axis; it is this group which is associated with Yiddish, a.k.a. Judeo-German. The name of Ashkenaz came to be identified with this region in the Middle Ages, possibly due to sounding a bit like “Skandza,” a Byzantine name for the supposed homeland of the Germans. Ashkenaz denotes the majority of Europe, barring northern Europe (the British Isles, Finland, and Scandinavia) and most of the Mediterranean littoral. Other parts of Europe developed their own Jewish ethnicities, the most famous being the Sephardim of southern France, Portugal, and Spain.

9In what follows here, I’m heavily indebted to Gary Anderson’s That I May Dwell Among Them: Incarnation and Atonement in the Tabernacle Narrative, which came out a couple of years ago. It marks a magnificent return of Catholic theology to the contextual meaning and imagery of the sacrificial system set forth in the Torah, from which all of Catholic worship is ultimately derived—even the liturgy of the hours! Even if one is going to allegorize a text (as the Apostles and Fathers often do), one must first understand it in its original literary significance, and Anderson really did his homework.

10As far as I can conjecture, Hamartia and Parabasis are credibly possible Greek-derived terms that might have developed if the emphasis been laid on the חַטָּאת or אָשָׁם forms of offering. I for one am glad these terms weren’t used, especially since parabasis is a term in Greek drama, which could have gotten confusing for a Classicist. I’m even more grateful that the burnt offering did not form a basis for the sacrament’s name; the Greek equivalent term for that is ὁλόκαυστον [holokauston].

11There are even contexts where you wouldn’t expect the article to appear although the noun in question is definite. (This is what’s going on in John 1:1; with apologies to the Watchtower Society, Charles Taze Russell just didn’t know Greek as well as he thought he did.)