Luke 11

Bethany today, located in the West Bank,

adjacent to Jerusalem. Photo by Tomer Hu,

used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

The Gospel for this past Sunday (the Seventeenth in Ordinary Time, or Sixth after Trinity by the English calendar) contains the Lord’s Prayer and some of Jesus’ teaching about it. By an intriguing coincidence, this is also the chapter of Luke in which we meet SS. Martha and Mary of Bethany, in probably their most famous story (the “Lord, tell Mary to help me make dinner instead of sitting there listening to you” story),1 which afterwards the Medievals interpreted as an allegory of the active and contemplative lives; and today, the 29th of July, is their memorial, along with that of their brother St. Lazarus (who, in the allegory, has been allegorized as the third part of the Christian life, penitence).

Now, I’ve translated the Lord’s Prayer from the Greek before, relatively recently, in four parts; here are links to the parts each post covers:

Our Father … as it is in heaven (petitions 1-3).

Give us … bread (petition 4).

And forgive us … who trespass against us (petition 5).

And lead us … from evil (petitions 6-7).

Nonetheless, I’ll be translating it again, because Luke relates this prayer in a slightly different form from Matthew. (At least, he does so in the best manuscripts; such a popular text was especially vulnerable to harmonization by copyists, both deliberate and unconscious.) It’s also noteworthy that, while both evangelists mention Jesus teaching after delivering the text of the prayer, his focus differs from one Gospel to the other: Matthew’s is on forgiveness, while Luke’s is on supplication.

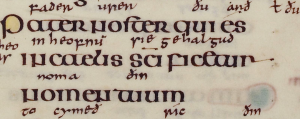

The beginning of the Our Father in the

Lindisfarne Gospels; its Latin text is

annotated in the Northumbrian dialect

of Old English.

Luke 11:1-13, RSV-CE

He was praying in a certain place, and when he ceased, one of his disciples said to him, “Lord, teach us to pray, as John taught his disciples.”a And he said to them, “When you pray, say:

“‘Father, hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come. Give us each day our daily bread; and forgive us our sins, for we ourselves forgive every one who is indebted to us;b and lead us not into temptation.'”

And he said to them, “Which of you who has a friend will go to him at midnight and say to him, ‘Friend, lend me three loaves; for a friend of mine has arrived on a journey, and I have nothing to set before him’; and he will answer from within, ‘Do not bother me; the door is now shut, and my children are with me in bed;c I cannot get up and give you anything’? I tell you, though he will not get upd and give him anything because he is his friend, yet because of his importunitye he will rised and give him whatever he needs. And I tell you, Ask, and it will be given you; seek, and you will find; knock, and it will be opened to you. For every one who asks receives, and he who seeks finds, and to him who knocks it will be opened. What father among you, if his son asks for a fish, will instead of a fish give him a serpent; or if he asks for an egg, will give him a scorpion?f If you then, who are evil,g know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will the heavenly Fatherh give the Holy Spiriti to those who ask him!”

Luke 11:1-13, my translation

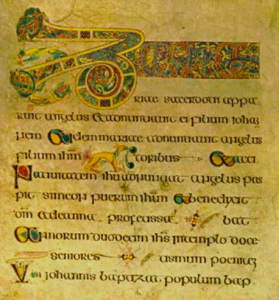

Part of a page of Luke from the Book of Kells.

Now, it happened that he was in a certain place praying; as he stopped, some one of his students said to him, “Sir, teach us to pray, just as John taught his students.”a

He told them, “Whenever you may pray, say: ‘Father, your name be sanctified; your kingship come; our bread on which we subsist, give to us each day; and remit our sins for us, for we ourselves also remit every debtor of ours;b and do not lead us into trial.'”

And he said to them, “If some one of you has a friend and you go to him in the middle of the night and tell him, ‘Friend, lend me three loaves—you see, a friend of mine came off the road to me, and I don’t have anything to set before him’; won’t the other say in reply, ‘Don’t bother me; already the door has been shut, and my children are with me in the bed:c I cannot get back up to give you something.’ I tell you, if he will not get back upd and give something to him because he is his friend, still, because of his shamelessness,e he will rouse himselfd to give, to lend him something. And I tell you: ask, and it will be given to you; search, and you will find it; knock, and it will be opened for you; for everyone who asks receives, and everyone who searches finds, and to everyone who knocks, it will be opened.

“Say a son asks some father among you for fish—and will he give him a snake in place of fish? Or say he asks for an egg, will he give him a scorpion?f Then if you, being the wicked,g know to give good gifts to your children, much more rather will the Father who is from heavenh give the Holy Spiriti to those who ask him.”

The Spirit as a dove, from Cathedra Petri

(1666) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini; photo by

Wikimedia contributor Dnalor 01, used under

a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

Textual Notes

a. as John taught his disciples/just as John taught his students | καθὼς καὶ Ἰωάννης ἐδίδαξεν τοὺς μαθητὰς αὐτοῦ [kathōs kai Iōannēs edidaxen tous mathētas autou]: The influence of St. John the Baptist upon late Second Temple Judaism was rather greater than we sometimes recognize. Acts 19 mentions disciples of the Baptist being present in Ephesus around twenty years after his death, and he is one of the few New Testament figures mentioned by Josephus. The Mandæan faith of southern Iraq (the only form of Gnosticism to arise in antiquity and survive to the present day) reveres John the Baptist as the last and greatest of its prophets, despite the fact that it considers both Abraham and Jesus Mandæan apostates.

b. forgive us our sins, for we ourselves forgive every one who is indebted to us/remit our sins for us, for we ourselves also remit every debtor of ours | ἄφες ἡμῖν τὰς ἁμαρτίας ἡμῶν, καὶ γὰρ αὐτοὶ ἀφίομεν παντὶ ὀφείλοντι ἡμῖν [afes hēmin tas hamartias hēmōn, kai gar autoi afiomen panti ofeilonti hēmin]: The parallels between the Matthean and Lucan versions of the Our Father are fairly obvious, so it’s interesting to see what Luke’s version leaves out. Consider the text below—red denotes text present only in Matthew; purple, text that appears in a different form in Luke:

Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come.

Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread,

And forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those that trespass against us.

And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil.

The salutation is simplified, and the third and seventh petitions are left out entirely (presumably their intent is felt to be covered by the second and sixth); the wording of the fifth is also changed, speaking of ἁμαρτίας, “sins,” instead of ὀφειλήματα [ofeilēmata], “debts.” Given Luke’s focus on the poor, we might have expected it to be him that sticks more consistently to the analogy of a debt to be paid when discussing sin, but nope, it’s Matthew. I don’t really know what, if anything, to make of these differences (but see notes g and h for more in this vein).

Some commentators put intertextual differences of this type down to one form being the more “primitive” and the other “embroidered” by later generations of Christians. While this is not impossible, I think Dorothy Sayers’ explanation is far more economical: Jesus probably had to repeat most if not all of his teachings many times to a wide variety of audiences. It would be quite natural for different occasions to see different phrasing, and according for more than one tradition of “what he really said” to develop, and perhaps be preserved.

TIL that Ancient Egyptian pillows could look

like this. Photo by … I’m not sure?, used under

a CC BY 4.0 license (source).

c. my children are with me in bed/my children are with me in the bed | τὰ παιδία μου μετ’ ἐμοῦ εἰς τὴν κοίτην εἰσίν [ta paidia mou met’ emou eis tēn koitēn eisin]: At the time, and through the Middle Ages, it was commonplace in most houses (aside from the wealthiest) to have a single place to sleep, used by the entire family. For anyone to get up in the middle of the night would at least risk making everyone get up in the middle of the night.

d. get up … rise/get back up … rouse himself | ἀναστὰς … ἐγερθεὶς [anastas … egertheis]: The puns here may not be intentional. Regardless, two distinct verbs, both of which are used throughout the rest of the New Testament to describe the Resurrection, occur right next to each other here—you may recognize ἀναστὰς in particular for its kinship to the Greek noun, eventually borrowed as a Russian and English name, “Anastasia.”

e. importunity/shamelessness | ἀναίδειαν [anaideian]: The thing the friend is being shameless about is importunity, certainly. However, what ἀναίδεια means is the quality of being without shame; more exactly, of being without αἰδώς [aidōs], which was the name both for a quality of character and a minor goddess in Greek myth (supposedly the last to leave the earth at the close of the Silver Age). “Shame,” “reverence,” “humility,” or “modesty” are common translations; “decency” or “piety” might do as well, possibly even “self-consciousness”! I have a hunch that, if they were familiar with 2000s-2010s humor, the ancient Greeks would say that αἰδώς is the quality which makes a person socially aware enough to cringe.

f. scorpion | σκορπίον [skorpion]: Most scorpions are harmless to humans—only twenty-five species, or one percent of the total number of species, possess a potentially human-lethal venom. However, you will note that this means the number of scorpion species (which as arachnids are, to be frank, pushing it in the first place) is a thoroughly unacceptable 2,500, give or take. Moreover, I was made—quite angrily—aware, while reading up about them a bit, that the native range of scorpions-in-general looks like this:

The green represents evil

In short, I’d like them to stop it, please and thank you.

g. who are evil/being the wicked | πονηροὶ ὑπάρχοντες [ponēroi hüparchontes]: These two words are each rather interesting individually. The latter is another form of the verb ὑπάρχω [hüparchō], discussed in textual note c of this post; it is generally a being verb, but more active than most being verbs are.

Πονηροὶ, which I have here rendered “wicked,” is a plural form of an adjective that appears in the singular in … the Lord’s Prayer! Namely, it occurs in the seventh petition of the Matthean form, one of the two petitions that the Lucan version of the prayer omits: “deliver us from evil” or “from the evil one” is in fact a request to be delivered from the πονηροῦ [ponērou], which I translated in my initial post on the Our Father as the “oppressor.” Its earliest meaning was “toilsome, wearying”; it came later on to have a moral tone, best rendered as “oppressive, cruel”; and eventually the word lost everything but its moral tone, and took on the meaning of “bad” or “evil.”

h. the heavenly Father/the Father who is from heaven | ὁ πατὴρ ὁ ἐξ οὐρανοῦ [ho patēr ho ex ouranou]: This phrase is rather intriguing—for one thing, it provides an almost exact parallel to the parts of the salutation in Matthew’s version of the Our Father that Luke’s does not include. The only distinction is that here, the Father is “from heaven” (ἐξ), rather than “in heaven” (ἐν).

i. the Holy Spirit | πνεῦμα ἅγιον [pneuma hagion]: This is rather puzzling, not linguistically but just in terms of content. There has been no mention of asking for the Holy Spirit before now; Jesus seems to be introducing this out of the blue, yet the text treats it like something unremarkable, as if asking for the Holy Spirit were obviously what prayer is for in the first place.

Holy Nagging

This is not a text about which I find I can say much, because it is addressed to one of my most ingrained vices (and one that does not feel like a vice): an all but overpowering reluctance to ask for things. My instinctive feeling is generally that to ask someone for something is, almost in itself, annoying, and that whoever asks the least deserves the most. On some level, it would be sheer nonsense to apply this to God even if it were true in the first place; I don’t think one can seriously expect normal rules about asking for things to apply to the ground of existence as such, and obviously it’s silly to think that the eternal God is going to be irked by a demand on his time.

More than that, the attitude of this passage is clearly the opposite. It does not shame, scold, or condemn those who are shy, uncertain, or desperate. But its advice is encouragement, yet without comfort—it is not soothing. It promises (in a modern idiom) “results,” but it does so for the persistent, and therefore advises persistence. Speaking for myself, I don’t like being advised to persist, because it’s essentially the same thing as being advised to be patient. But, it seems to be kind of a “tough, suck it up” thing here.

Footnotes

1Which, to be honest, is kind of a pity for St. Martha. Like St. Thomas, I feel, she is most remembered for committing a dreadfully silly, yet at the same time fairly natural sin—the kind most of us probably commit every day, perhaps without even noticing, let alone repenting. Yet in John 11, when her brother has just died because Jesus arrived (as any of us would have called it) too late, and before Jesus has given any clear sign that he is about to do something unusual, it is also St. Martha who says boldly (v. 27), “I believe that thou art the Christ, the Son of God, which should come into the world.”