I Tell You a Mystery

Our Gospel for 24 August, the Tenth Sunday after Trinity (which equates, this year, with the Twenty-first Sunday in Ordinary Time), touches on a difficult topic in theology. It is a topic that has driven, maybe, more intellectual wars among nerdy, overchurched fourteen-year-olds than any other. It is the doctrine of election, or as it is also called, predestination.

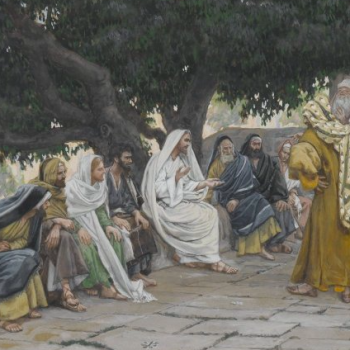

The Lord’s Prayer (1896), by James Tissot.

Some people think that only Reformed Christians, a.k.a. Calvinists, believe in predestination; a great many people think belief in predestination (regardless of how it’s explained) means disbelieving in free will. Both of these ideas are mistaken. There are specific versions of the notion of predestination that are determinist, sure, but that no more makes this doctrine determinist than the Christian belief in the Trinity makes all monotheism trinitarian. Moreover, it’s worth pointing out that despite the popular notion of what Reformed theology consists in, most of its adherents do believe in free will.1

Moreover, Catholics believe in predestination too; the doctrine appears in Scripture (e.g. Ephesians 1:3-12, Romans 8:22-31). However, we don’t talk or think about it nearly as often as our Reformed brethren, for a variety of reasons. For one thing, Scripture is not very explicit on how election works, ontologically; the Church permits a variety of views. (Personally, I have no view of predestination more specific than “It’s a thing.”) Moreover, given that the sense in which God is the cause of things is so radically different from our normal experience of causation, it makes sense that we’d have a difficult time parsing it! And, without saying that “being practical” is the only value an idea can have, I would argue that predestination is not a very practical topic to theologize about, because we don’t know what God has decreed within himself, and on the whole don’t need to before we know what our duty is in the here and now. The Holy See has established only a few “hard no’s” about election—for instance, she firmly rejects the notion that God predestines anyone to be damned, a doctrine which is now quite uncommon among Protestants too.

“Lord,”

But thereby hangs a tale; for there is one aspect of the doctrine of election that Catholics of a certain type do love to talk about. It’s the very question put to Jesus in this Gospel text: “Are there few that be saved?”

The Triumph of St. Thomas Aquinas, Doctor

Angelicus (1366), by Andrea di Bonaiuto.

Now, the obvious way of replying to that question is with some factual statement—whether one as simplistic as yes or no, or one so nuanced it’d scare SCP-738. But, in the vein of ice being less dense than water, the Resurrection, and the platypus, our Lord once again does not do the obvious thing; in fact, he doesn’t answer the question at all. To a question seeking information, something in the indicative, he replies with how to act, in the imperative. Why?

Many Catholic theologians over the centuries have seen fit, for whatever reason—and there may have been good ones, I don’t know—to propose their own, less Delphic answers. These answers fall into two basic types, widely known as universalism and infernalism.2 The former is the view that all men will be saved; the latter, that at least some will be damned. Here again, only a few doctrines have been ruled “right out”: at least one version of apocatastasis (a form of universalism that encompasses angelic beings as well as humanity) was condemned at the Second Council of Constantinople in 553, and any version of either infernalism or universalism that denied free will would ipso facto be out of court.

What about the saints and doctors of the Church? A few have been hopeful universalists,3 from Origen and St. Gregory of Nyssa down to St. Edith Stein and Hans Urs von Balthasar. Others, including celebrated names like those of St. Augustine and St. Thomas, have given the opinion that, yes, only a few will be saved, and a majority of the human race will be damned; on some infernalist showings, it will be an overwhelming majority. There is an elegant Latin phrase associated with this horrifying idea4 (isn’t there always)—namely, that the bulk of the human race form a massa damnata, a mass or lump of the condemned. Some Catholics are, groundlessly, insistent that this be taught as the only orthodox position. But let’s turn to the text.

The first page from an 11th-c. Byzantine

manuscript of the Gospel of Luke.

Luke 13:22-30, RSV-CE

He went on his way through towns and villages, teaching, and journeying toward Jerusalem. And some one said to him, “Lord, will those who are saved be few?” And he said to them, “Strive to enter by the narrow door; for many, I tell you, will seek to enter and will not be able. When once the householder has risen up and shut the door, you will begin to stand outside and to knock at the door, saying, ‘Lord, open to us.’ He will answer you, ‘I do not know where you come from.’ Then you will begin to say, ‘We ate and drank in your presence, and you taught in our streets.’ But he will say, ‘I tell you, I do not know where you come from; depart from me, all you workers of iniquity!’ There you will weep and gnash your teeth, when you see Abraham and Isaac and Jacob and all the prophets in the kingdom of God and you yourselves thrust out. And men will come from east and west, and from north and south, and sit at table in the kingdom of God. And behold, some are last who will be first, and some are first who will be last.”

Luke 13:22-30, my translation

And he was going along through the cities and towns, teaching and making his way toward Jerusalem. Someone asked him: “Sir—whether the saved will be few?”

He said to them, “Contend to come in through the narrow door, because many, I tell you, will seek to come in and will not have the strength to; from whenever the master of the house rises and shuts up the door, you too will begin to stand outside and knock on the door, saying, ‘Sir, open up for us’; and in answer he will say: ‘I do not know where you are from.’ Then you will begin to say, ‘We ate and drank in front of you, and you taught in our broadways’; and he will say to you, ‘I do not know where you are from: remove yourselves from me, all doers of injustice.’ There, there will be wailing and the grinding of teeth, whenever you shall see Avraham and Yitzhaq and Yakov and all the prophets in the kingship of God, while you are thrown out. And they will come from sunrise and sunset and from north and south and sit themselves down at table in the kingship of God. And look, they are the last ones, who will be first, and they are the first ones, who will be last.”

Anonymously-written 16th-c. Orthodox ikon

of the Apocalypse of St. John.

Textual Notes

a. will those who are saved be few/whether the saved will be few | εἰ ὀλίγοι οἱ σῳζόμενοι [ei oligoi hoi sōzomenoi]: Hyper-literally, the wording here is “if few the saved,” with the rest of the question left to be picked up by implication. Evidently this was a current debate in the synagogue, too.

The canny reader will have noticed that I never answered this question in the introductory material either. This is because I don’t think our Lord’s prompt change of subject was arbitrary, or merely a response to the particular audience he happened to be addressing; I tend to think that for most people, regardless of time period or circumstances, the question of whether the saved are many or few is simply and solely a distraction. It’s a question about an urgently practical topic, yet one that ignores the issue Jesus immediately puts back in the center: what to do.

What’s especially bad about this specific distraction is its tendency to generate controversy, controversy which is entirely impractical—we do not know the mind of God about the predestination of any individual, after all—yet which often gets quite as heated as the hell it proposes to populate (or depopulate). In other words, it’s an effective way of sowing discord, while at the same time having no upside, no clear benefit to be gained by holding the controversy anyway. So why linger over it at all? It doesn’t seem to have any tendency to produce charity in the hearts of those who meditate upon it; both proponents of the massa damnata doctrine and, more surprisingly, a large proportion of the universalists I’ve seen in print, have been among the nastiest people I’ve had the displeasure of reading. Every angle I look at the issue from seems to furnish a fresh reason to mentally “change the subject” from this curiosity.

Dante and Virgil in Hell (1850), by William-

Adolphe Bouguereau. I believe this image is

from the Ninth Ditch of the Eighth Circle,

where sowers of discord are punished.

b. Strive/Contend | Ἀγωνίζεσθε [agōnizesthe]: The verb here has the primary meaning “struggle” or “strive,” but is also the default verb for competing in an athletic event. (It is related to the words protagonist and antagonist.)

c. I do not know where you come from/I do not know where you are from | Οὐκ οἶδα ὑμᾶς πόθεν ἐστέ [ouk oida hümas pothen este]: I find something about this phrase quite chilling. Not simply “I do not know you”—a phrase that, coming from the lips of the Omniscient, would be horrifying enough—but “I do not know where you are from“: the entire origin and context of the person thus addressed, it would seem, are alien to the speaker.

d. iniquity/injustice | ἀδικίας [adikias]: The primitive Greek word for “justice” is δίκη [dikē], sometimes personified as a goddess. (The closely-related goddess Ἀστραία [Astraia], ruler of innocence, right, and purity, was sometimes held to be the same being, and was the last to depart from dwelling among mankind at the close of the Silver Age; according to her myth, she was translated into the heavens as the constellation Virgo.) Δίκη forms the root of words like ἀδικία, δίκαιος [dikaois] “just” (as in “Aristides the”5), and δικαιοσύνη [dikaiosünē], which is conventionally rendered “righteousness,” as the suffix -σύνη is often used to form qualities of character from adjectives.

It may be my imagination, but I feel as though English-language Bibles tend to avoid the word justice, giving preference to the word righteousness. This bothers me a bit. Justice is something that implicitly has a social dimension; righteousness seems to carry no such implications. If this isn’t my imagination, the preference for this asocial term over a communal one suggests, among English speakers, a widespread dislocation of the brain, or the heart, with regard to the fundamental nature of morality—one that I definitely think is evident in American culture, which is downright poisonous in its individualism, whether it’s the fault of how we translate our Bibles or not.

e. There you will weep/There, there will be wailing | ἐκεῖ ἔσται ὁ κλαυθμὸς [ekei estai ho klauthmos]: Curiously, the RSV changes an impersonal description of a situation (“there will be weeping”) into a second-person future statement (“you will weep,” etc.)

Stories of Jacob and Isaac (14th c.), by Giusto

de’ Menabuoi, a Florentine painter thought

to have studied under Giotto.

f. Abraham and Isaac and Jacob/Avraham and Yitzhaq and Yakov | Ἀβραὰμ καὶ Ἰσαὰκ καὶ Ἰακὼβ [Abraam kai Isaak kai Iakōb]: As in my previous post, I’ve here used English forms adapted more directly from the original Hebrew forms and pronunciations of the Patriarchs’ names, rather than the conventional Hellenized versions. Interestingly, you can hear a certain amount of onomatopoeia in the fact that the name Yitzhaq means “laughter.” (Also, I remain in mild awe of the British Isles’ power to completely garble Biblical names: even knowing how we got there, it astonishes me that the English James and Gaelic Seamus are somehow6 our versions of Yakov. Even Welsh at least produced Iago, which has the decency to include a plosive, and a plosive that’s almost of the right phonetic series, no less.)

g. sit at table/sit themselves down at table | ἀνακλιθήσονται [anaklithēsontai]: As you may, gentle reader, be aware already, in the classical world, one did not necessarily sit at table; it was more customary to recline (a fact about which the film The Passion of the Christ makes gentle fun in one of its—naturally—vanishingly few lighthearted moments). At more “posh” events, or in wealthier households, this would be done in a τρικλίνιον [triklinion], a term borrowed into Latin as trīclīnium: “three couches” would be a literal translation (though they were really not so much couches as chaises longues), but “dining room” is the real equivalent. The idea was that a central table bearing the food and drink would be set in the middle, surrounded on three sides by diners, with the fourth side open for servants (who might or might not be slaves) to remove empty dishes, supply new ones, refill flagons of wine—that sort of thing. (This layout still coincidentally exists in 茶屋 [chaya], Japanese teahouses, the main avenue of geisha performances.7) Trīclīnia were not generally used for every meal; they connote a formal event, often held to honor one of the guests.

A reconstruction of a trīclīnium for three.

When St. John is described as “lying on

Jesus’ bosom,” the implication is that

they’re sharing a dining couch.8

h. some are last who will be first, and some are first who will be last/they are the last ones, who will be first, and they are the first ones, who will be last | εἰσὶν ἔσχατοι οἳ ἔσονται πρῶτοι, καὶ εἰσὶν πρῶτοι οἳ ἔσονται ἔσχατοι [eisin eschatoi esontai prōtoi, kai eisin prōtoi hoi esontai eschatoi]: There’s a slight vagueness in the Greek here, which the RSV renders by inserting “some” into each half of the chiasm.9 It isn’t clear from Jesus’ phrasing whether this is a general statement about the first and last (i.e. that their places will be switched categorically, as it were), or whether it’s more in the vein of “some of the placements in the list will surprise you.” On analogy with the maxims of the Beatitudes, the former seems to make more sense, but it’s hard to be sure.

Footnotes

1And in having a sense of humor, believe me or believe me not. I think literally every time in my life I’ve heard a person refer to the Reformed as “the frozen chosen,” that person has been Reformed; better than that is what a former leading pastor at my last Reformed church once said he often brought up in membership interviews. “Jesus said ‘I’ve come not to call the righteous but sinners,'” he said once in a sermon, “so one of the requirements to join this church, or any church, is to be a sinner’; and sometimes I’ll add, maybe under my breath, ‘And to join a Presbyterian church, you have to be totally depraved.'” (If you didn’t grow up Reformed and are waiting for the punchline, a doctrine called “total depravity” is an important element in Reformed theology; it’s explained well from that perspective here. Catholics generally dispute total depravity, and there are definitely versions of it that are incompatible with Catholicism, though I think the divergence is in some ways more apparent than real; Reformed believers are often taxed with believing things they don’t, for some of the same reasons people misunderstand Catholics when we use terms like substance or necessary or infallible.)

2Normally I try to stick to self-labels when describing any group’s beliefs. This is an exception; I don’t think I’ve ever heard someone describe themselves as an infernalist. However, this is the only term I’ve come across for describing this belief—the only one that doesn’t beg the question by appropriating labels like “orthodox,” anyway—so until I hear of a better one, it’ll have to do.

3I say “hopeful” here because (as far as I have read them) it accurately describes Stein and Balthasar; as for Origen and Gregory, I have read only a very little of their work, none of it dealing with their ostensible universalism, and have gotten conflicting reports about both men from other sources. I therefore don’t know whether to interpret them as dogmatic universalists or only as hopeful ones, but I trust that they can at least be classed as the latter.

4It is, in my opinion, significant—and does not signify anything good—that, when I described this idea as “horrifying,” a great many readers will have immediately inferred that I consider this idea untrue, reacting with irritation or approval dependent on their own beliefs. But this inference is entirely without validity. There is no possible way of getting from the claim This is horrible to the claim This is false, except via the claim Horrible ideas cannot be true—which no adult could possibly take seriously. Now, most of the universalists I’ve read or spoken with have made some form of the argument “God wouldn’t do that,” but that is not the same thing as pretending that horrible ideas cannot be true; admittedly, I’m not satisfied by the universalist arguments I’ve encountered, but they are not the rock-stupid fallacies they’re sometimes depicted as. Far more disquieting to me are the infernalists who, when people call the notion that most of mankind will be damned “horrifying,” react not only with annoyance (which a lot of us feel when disagreed with) but with indignance. As if the obvious thing is to be content with this. That is an outlook I consider profoundly sick, on both the natural and supernatural levels. Then again, while I have found this outlook among some infernalists, it is by no means (heh) universal among them, while on the other hand, I have consistently heard universalists talk breezily about infernalism as if everybody who believed it wanted people to go to hell—as though that were the only possible motive for not immediately adopting universalism. I find any view of that kind not only arrogant, but entirely too ready to make utterly repulsive assumptions about the character of its opponents.

5Aristides the Just was a statesman of classical Athens, and, incidentally, the father-in-law of Socrates. Aristides earned his moniker through his extreme devotion to principle and to the law, at the expense of all personal favor or resentment. One of the most famous stories about him, and probably the funniest, comes from an occasion when Athens was voting on an ostracism (a ten-year banishment of any citizen who was becoming too powerful, to prevent such people from gaining enough clout to overthrow the constitution); voting was done by scratching the person’s name onto a pottery shard, or ὄστρακον [ostrakon], which was basically the scrap paper of the ancient world. While the vote was being held, an illiterate citizen approach Aristides and, not recognizing him, asked him to incise the name Aristides onto his voting shard. Moved by curiosity, the statesman asked the stranger whether he had suffered some injury at Aristides’ hands, to which the other replied, “No, I’ve never even met him—I’m just sick of hearing everybody call him ‘the Just’ all the time.” His curiosity sated, Aristides duly scratched his own name onto the fellow’s ostrakon, and was promptly rewarded with ten years’ exile. (They did let him come back early—accounts vary as to how long he was away, ranging from two to five years—on account of him also being an outstanding general whose help they could really use in fighting the Persians. He then helped mastermind the crucial Greek victories at Salamis and Platæa, because it turns out that history is only about the size of the average high school.)

6In a “Somehow, Palpatine returned” sort of way.

7I don’t think this is still a widespread misconception, but just in case: no, geisha are not prostitutes. (There is, or was, a long tradition in Japan of wealthy men keeping a geisha mistress, but that’s really not the same thing in the first place, and is in any case incidental to actual geisha life and work.) What geisha are, is artists—the word 芸 [gei] means “craft, art”—and most geisha are musicians, actresses, dancers, singers, etc.; they remain unmarried because the conventional restrictions laid upon housewives by Japanese society would typically make the practice of any gei impossible, though this is less true today than it was in, say, 1925. (Also, lest I seem to profess an expertise I do not have: no, I don’t know Japanese, and I certainly don’t know kanji; I looked these up and am just hoping/assuming the sources I found were correct. But I did bother looking them up, because kanji are pretty.)

8The Greek of that passage (John 13:23) is striking: it describes the Beloved Disciple as being ἐν τῷ κόλπῳ τοῦ Ἰησοῦ [en tō kolpō tou Iēsou], “in the kolpos of Jesus.” A person’s kolpos is the area immediately in front of their thorax (hence the old-fashioned translation “bosom”); “lap” isn’t far from the same concept, except that that inherently involves sitting. What’s particularly interesting about St. John being described as being in Christ’s kolpos is that, back in 1:18, the evangelist tells us that the Son is “in the kolpos of the Father”; taken together with 19:35 and 21:24, this implies a claim to the highest degree of authority for the Gospel of John.

9Chiasm (or chiasmus) is a rhetorical device in which a thing—sentence, paragraph, whole narrative, what you will—has a mirrored, ABBA structure.