The Prince of Thy People

Instead of the upcoming Sunday, I decided to translate the epistle and Gospel for the day after: the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels, or Michaelmas (pronounced micklemuss) in the Anglican tradition. As a Gabriel, it’s my name-day. There turned out to be a good deal more material than I had expected, so I made it a two-parter!

This is one of several holidays eliminated by (some) Protestant Reformers for reasons I can’t possibly fathom. And it sounds even cooler in the East, where it’s “St. Michael and all the bodiless powers.” How do you beat that? it’s just great. The archangels explicitly honored by the Latin Catholic Church are SS. Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael. Michael is known to us from the books of Daniel, Jude, and Revelation, Gabriel from Daniel and Luke, and Raphael from Tobit; St. Raphael’s name also occurs in the book of Enoch, treasured by the Ethiopian Church (of which more in a moment). All three names are of Hebrew origin:

Michael ⇐ מִיכָאֵל [Mykhâ’êl] = Who is like God?

Gabriel ⇐ גַּבְרִיאֵל [Gavry’êl] = God is my strength (though the meaning “man of God” is occasionally given)

Raphael ⇐ רָפָאֵל [Râfâ’êl] = God heals

Assumption of the Virgin (1476), by Francesco

Botticini. Nine separate orders of angelic beings

are distinguished.

St. Michael in particular, referred to in Daniel as “the prince of your [Daniel’s] people,” i.e. the Jews, is taken by Catholic Christians as the the Principality of the Church as well. If he is a Principality, which … okay, better to just start from the beginning. Here’s the broadly-agreed Catholic angelic taxonomy:

FIRST CHOIR

This choir’s activities are all essentially celestial, rather than concerned with created things.

Seraphim (Heb. שְׂרָפִים [š’râfym], “burning ones” ⇒ Gr. σεραφείμ [serafeim]). These beings love and adore God more than any other.

Cherubim (Heb. כְּרוּבִים [kruuvym], “griffins”?1 ⇒ Gr. χερουβίν [cheroubin]). These beings understand God more clearly than any other.

Thrones (Heb. אוֹפַנִּים [‘oufannym], “wheels” | Gr. θρόνοι [thronoi], “thrones”). These beings are witnesses of God’s power and the bearers of his throne or chariot.

SECOND CHOIR

This choir are the main governors of physical creation.

Dominations (Gr. κυριότητες [küriotētes], “lordships”). These beings transmit God’s will to the five lower orders and guide their activities.

Virtues (Gr. ἀρεταί [aretai], “efficacies”). These beings maintain, or are, the “laws of nature.”

Powers (Gr. ἐξουσίαι [exousiai] “powers, authorities”). These beings guide the course of history.

THIRD CHOIR

This choir contains those orders chiefly concerned with human beings.

Principalities (Gr. ἀρχαί [archai], “sources”). These beings govern and protect groups of people or places.

Archangels (Gr. ἀρχάγγελοι [archangeloi] “prime-messengers”). These beings seem to be literally the messengers of God, revealing things at his will to a given person.

Angels (Gr. ἄγγελοι [angeloi], “messengers”). These are our guardian angels.

There are some catches in this, though. One is that this is speculative theology; it draws on divine revelation, but this schema, as such, is not revealed. Some readers may also have noticed that St. Michael is called an “archangel” in the Bible, yet according to this setup, he ought to be a Principality (and he is also referred to as a “prince”). Whether “archangel” originally denoted a specific order of beings, or was simply a generic word for the higher kinds of angels, is unclear. It also rather problematizes the notion of “seven archangels who stand before God,” as the obvious assumption based on this setup would be that there are no archangels who stand before God, that only the orders of the First Choir do that.

However, it is well worth remembering: the only people who actually need to have all this information correct and keep it straight are the angelic beings themselves. It might be a bummer, but it is totally fine, if we have it wrong.

Raphael, Michael, Uriel, and Gabriel in stained

glass at the Church of St. James in Grimsby,

England. Photos by Jules & Jenny, used under

CC BY 2.0 licenses (source and source).

If you aren’t interested in angelic magic, lost books of the Bible, the identity of the infamous nephilim, and so on, feel free to skip the small-print bit here. It’ll only bore you.

An Inessential Detour Through the Book of Enoch

One additional archangel is often recognized in the Anglican and Lutheran traditions, a St. Uriel (occasionally spelled Oriel or Auriel; the name means “God is my light,” from the Hebrew אוּרִיאֵל [‘Uury’êl]—the intrusive a of “Auriel” is basically a flawed representation of the initial ‘âlêf). John Milton used the name for one of the obedient angels in Paradise Lost.

The earliest mention of this Uriel appears to be in the book of Enoch. There, he is one of the angels who remains faithful to God and does not join the rebellion of Shemihaza, or Samyaza.2 (To all appearances, the author of Enoch attributed the angelic fall to this alone: the mythos of Satan as the primordial sinner was either absent from his thought or dismissed by him.) This Samyaza was the leader of the Watchers, a class of angelic beings mentioned in Daniel 4, though it is unclear from that text whether “Watcher” is a kind of being or more of a job description; they are also referred to as the Grigori, a Church Slavonic borrowing of the Greek ἐγρήγοροι [egrēgoroi], meaning “wakeful.” According to a very ancient story, Samyaza persuaded two hundred of his fellow spirits to bind themselves in a covenant to revolt against God by taking human women as wives. This mythos may be reflected in Genesis 6:1-4:

And it came to pass, when men began to multiply on the face of the earth, and daughters were born unto them, that the sons of God saw the daughters of men that they were fair; and they took them wives of all which they chose. And the Lord said, “My spirit shall not always strive with man, for that he also is flesh: yet his days shall be an hundred and twenty years.” There were giants in the earth in those days; and also after that, when the sons of God came in unto the daughters of men, and they bare children to them, the same became mighty men which were of old, men of renown.

This is the famous passage about the נְפִילִים [n’fylym], the nephilim (naphil in the singular). The name probably means “fallen ones,” as it certainly contains the radical נפל [n-p-l], which encodes the idea of falling; I’m given to understand that there is some doubt as to whether the “falling” in question must be intransitive in sense, or could instead be transitive—in other words, whether the name might possibly mean “those who cause others to fall,” or (as we might say in archaic English) “fell ones.”3 This is based on interpreting the expression “sons of God” as referring to angels, which is consistent with its other appearances in the Hebrew Bible (e.g. in Job 38:7). The book of Enoch, which was familiar to the primitive Church but not widely regarded as canonical, gives a more expansive version of the story.

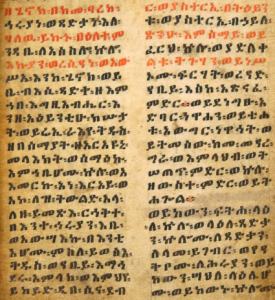

The beginning of Enoch in Ge’ez, the liturgical

language of the Ethiopian Churches.4

And it came to pass when the children of men had multiplied that in those days were born unto them beautiful and comely daughters. And the angels, the children of the heaven, saw and lusted after them, and said to one another: “Come, let us choose us wives from among the children of men and beget us children.” And Samyaza, who was their leader, said unto them: “I fear ye will not indeed agree to do this deed, and I alone shall have to pay the penalty of a great sin.” And they all answered him and said: “Let us all swear an oath, and all bind ourselves by mutual imprecations not to abandon this plan but to do this thing.” Then sware they all together and bound themselves by mutual imprecations upon it. And they were in all two hundred; who descended in the days of Jared [the father of Enoch, and thus the great-great-grandfather of Noah] on the summit of Mount Hermon … And all the others together with them took unto themselves wives, and each chose for himself one, and they began to go in unto them and to defile themselves with them, and they taught them charms and enchantments, and the cutting of roots, and made them acquainted with plants.

And they became pregnant, and they bare great giants, whose height was three thousand ells:5 who consumed all the acquisitions of men. And when men could no longer sustain them, the giants turned against them and devoured mankind. And they began to sin against birds, and beasts, and reptiles, and fish, and to devour one another’s flesh, and drink the blood. Then the earth laid accusation against the lawless ones.

The Sons of God Saw the Daughters of Men That

They Were Fair (1923), by Daniel Chester French.

Photo by Daderot.

And Azazel taught men to make swords, and knives, and shields, and breastplates, and made known to them the metals of the earth and the art of working them, and bracelets, and ornaments, and the use of antimony, and the beautifying of the eyelids, and all kinds of costly stones, and all coloring tinctures. And there arose much godlessness, and they committed fornication, and they were led astray, and became corrupt in all their ways. [The fallen angels] taught enchantments, and root-cuttings … the resolving of enchantments … astrology … the constellations … the knowledge of the clouds … and … the course of the moon. And as men perished, they cried, and their cry went up to heaven … And then Michael, Uriel, Raphael, and Gabriel looked down from heaven and saw much blood being shed upon the earth, and all lawlessness being wrought upon the earth.

—from Enoch 6:1-9:2 as given in The Apocrypha and Pseudepigraphica of the Old Testament, edited by R. H. Charles

But of course Enoch fell out of the familiarity of the West, during the Sturm und Drang of the collapse of Rome in the sixth to eighth centuries; further contact with the Ethiopic Church seems to have been lost until about the fifteenth century. Uriel, however, did not only appear here—he also appears in II Esdras, the worst book. (Okay, it isn’t really the book in itself that’s bad, but trying to keep track of the numbering of the books called Esdras, or Ezra, is an actual nightmare.6 The short version is, you’ll sometimes see this II Esdras referred to as IV Esdras, or occasionally III Esdras.) Georgian and Slavonic Bibles sometimes contain this book, usually as an appendix, or so I gather. It is therefore probably via the Slavs that the name Uriel reached Western Europe. Alternatively, it’s possible the name was picked up from Judaism. The name is Hebrew, after all, and Uriel often appears as one of the angels of the sephiroth, the attributes of God in the tradition of the Kabbalah, the principal form of Judaic mysticism from the thirteenth century forward. Some churches in the East profess to preserve the names of all seven archangels who are said to stand in the presence of God—see Tobit 12:15, Luke 1:19, and Revelation 1:4 for allusions to this idea—and the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox appear to agree in making Uriel one of them.

Nevertheless, the name does not occur in any writings held to be inspired by Rome. Names are treated as deeply important in the Bible, like extensions of the personality and not merely conventional titles, and this is nowhere more true than in the spiritual realm (often, the most important part of an exorcism is forcing the demon to disclose its name, which appears to break down its power of resistance); accordingly, the authorities of the Catholic Church recommend against using the name “Uriel” or invoking him in prayer. Inventing names for angels in general is also discouraged by the Church.

Michaelmas Customs

A cluster of (mostly unripe) blackberries.

Photo by Ragesoss, used under

a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

Michaelmas was an important date in the Medieval calendar of the British Isles, and several customs became attached to it. It is sometimes said to be the day that Satan, having been cast out of heaven, struck the earth. Goose and blackberries are traditional Michaelmas cuisine: according to one legend, Satan landed in a blackberry bush (perhaps the thorns led to the idea?), and blackberries should no longer be eaten after 29th September. As for geese, they are so clearly creatures of Satan that I assume no further elucidation is called for.

As fans of old-timey British media may know, Michaelmas is also a defining date in the collegiate calendar over there. The autumn terms at Aberystwyth, Cambridge, Durham, Lancaster, Oxford, and Swansea Universities, as well as of Trinity College, Dublin, all begin on Michaelmas, and are therefore known as the Michaelmas term (followed by Hilary term, the date of which is fixed by the Memorial of St. Hilary on 13th January, and Trinity term, named for Trinity Sunday).

Liturgically, Michaelmas is one of the turning-point feasts that demarcate the five subdivisions of Trinitytide:

- from Trinity Sunday (a moveable feast, falling in May or June) to the Solemnity of SS. Peter and Paul (29th June);

- from 30th June (the memorial of the first Roman martyrs) to the Assumption of the Mother of God (15th August);

- from 16th August to Michaelmas (29th September)—we’re on the verge of concluding this one;

- from 30th September (the memorial of St. Jerome) to Hallowmas (1st November);

- from All Souls’ Day (2nd November) to the last day of the liturgical year, which is always whichever day from 26th November to 2nd December is a Saturday (the Sunday from the 27th to the 3rd is always the First Sunday of Advent).

And finally—though I’ll grant that this is a newer custom, observed chiefly by me—I consider Michaelmas the beginning of the broader “spooky season” before Halloween and Día de los Muertos. My rationale here is, I like it.

Revelation 12:7-12b, RSV-CE

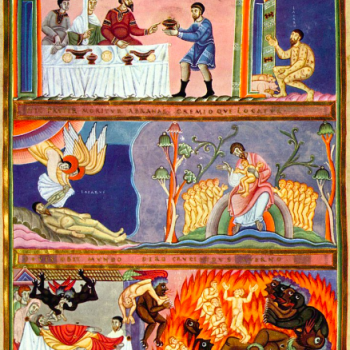

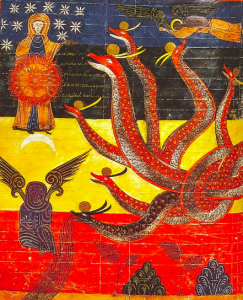

An illumination of the commentary on

Revelation by Beatus of Liébana, depicting

the Dragon and the Woman clothed

with the sun.

Now war arose in heaven, Michael and his angelsa fighting against the dragon; and the dragon and his angels fought, but they were defeated and there was no longer any place for them in heaven. And the great dragon was thrown down, that ancientb serpent, who is called the Devil and Satan,c the deceiver of the whole worldd—he was thrown down to the earth, and his angels were thrown down with him. And I heard a loud voice in heaven, saying, “Now the salvation and the power and the kingdom of our God and the authority of his Christ have come, for the accuser of our brethren has been thrown down, who accuses them day and night before our God. And they have conquered him by the blood of the Lamb and by the word of their testimony, for they loved not their lives even unto death.e Rejoice then, O heaven and you that dwell therein!

Revelation 12:7-12b, my translation

And there was war in heaven: Michael and his messengersa waged war on the dragon. The dragon too began waging war, and his messengers, but they were not strong enough—their place is no longer found in heaven. And he was cast out, the great dragon, the primordialb serpent, who is called the Accuser and Šâṭân,c who wanders around the whole inhabited worldd—he was cast down to the earth, and his messengers were cast down along with him.

And a great voice was heard in heaven that said: “Now have come the salvation and the power and the kingship of our God, and the authority of his Anointed, because the slanderer of our brothers is cast out, he who slanders them in front of our God day and night. And they defeated him by the blood of the Lamb and by the word of their witness, and did not love their life to the point of death;e rejoice over this, O heavens and you who dwell in them.

Textual Notes

I’ve translated this passage before; this text and its notes form part of a wider passage in this post.

a. Michael and his angels/Michael and his messengers | ὁ Μιχαὴλ καὶ οἱ ἄγγελοι αὐτοῦ [ho Michaēl kai hoi angeloi autou]: The word “messengers,” as elsewhere, is my more-literal-than-most rendering of ἄγγελος [angelos].

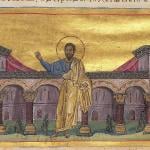

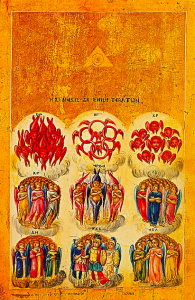

Orthodox ikon of the nine orders of

angelic beings.

This imagery more broadly is drawn from the book of Daniel, who represents the nations of the earth as being governed by, or embodied in, angelic intelligences. We would call these “principalities” today, that being the name of the angelic order that tends to countries and peoples. Daniel implies (e.g. in 10.13) that some of them are fallen; whether this means that some nations just have a fallen principality, or that nations, like individuals, may have both an appointed guardian that is obedient to God and a chronic tempter that is not, I don’t know.

b. ancient/primordial | ὁ ἀρχαῖος [ho archaios]: Elsewhere, I have probably translated ἀρχαῖος as “old” or “ancient,” which is correct enough. However, the term παλαιός [palaios] also has this meaning, and ἀρχαῖος is related to the word ἀρχή [archē], which means “source, origin, beginning” (for instance, the first words of the Gospel of John are Ἐν ἀρχῇ [en archē], “In the beginning”); I therefore wanted a term that would evoke the beginning.

c. called the Devil and Satan/called the Accuser and Šâṭân | ὁ καλούμενος Διάβολος καὶ ὁ Σατανᾶς [ho kaloumenos Diabolos kai ho Satanas]: The “translation” devil low-key bugs me. For all intents and purposes, “devil” the name of a type of creature in English, but there is no hint of this in the Greek διάβολος; it is the etymological ancestor of “devil,” but the two words’ meanings and usages are radically unlike one another (since the English has been determined not only by the Greek, but by the specifically religious sense of the Greek); διάβολος just means “slanderer, detractor,” without any specially theological bent. The pseudo-name שָׂטָן [šâṭân] was, likewise, an ordinary noun in Hebrew. It meant “enemy, adversary,” or perhaps something like “plaintiff,” aligning with its translation as διάβολος.

Illustration of the fall of Satan for Paradise

Lost (1866), by Gustave Doré.

d. the deceiver of the whole world/who wanders around the whole inhabited world | ὁ πλανῶν τὴν οἰκουμένην ὅλην [ho planōn tēn oikoumenēn holēn]: The RSV’s translation is certainly a very Johannine sentiment; my rendering is a little flat-footed, and I half suspect a sort of pun here on the author’s part—more on that shortly. But the RSV and I are, at least, both wrong, in that neither of us translated the participle in this sentence as a participle—they made it into a noun, “deceiver,” while I made it the finite verb “wanders.”

The actual word is πλανῶν, from πλανάω [planaō] meaning “to wander, stray,” which is the source of the word planet (this handful of “wandering stars” were contrasted with the far more distant “fixed stars” that made up the majority of the cosmos8). From wandering or going astray, one easily reaches the idea of erring or of leading people astray, hence the development of the word.

The Orion Nebula, photographed by the Hubble

Telescope (in a combination of visible and

infrared light).

The half-pun (I hope you remember it from earlier) that I think I detect is that, while πλανάω did already have its malicious sense at this time, Scripture does give us another description of Satan’s typical behavior; in fact, it’s given twice, in two successive chapters. Here is the text of the second, and see if you can’t detect any parallels to other parts of the Apocalypse (italics mine):

Again there was a day when the sons of God came to present themselves before the Lord, and Satan came also among them to present himself before the Lord.

And the Lord said unto Satan, “From whence comest thou?” And Satan answered the Lord, and said, “From going to and fro in the earth, and from walking up and down in it.” And the Lord said unto Satan, “Hast thou considered my servant Job, that there is none like him in the earth, a perfect and an upright man, one that feareth God, and escheweth evil? and still he holdeth fast his integrity, although thou movedst me against him, to destroy him without cause.”

And Satan answered the Lord, and said, “Skin for skin, yea, all that a man hath will he give for his life. But put forth thine hand now, and touch his bone and his flesh, and he will curse thee to thy face.”

—Job 2.1-5

Ikon of Job (17th c.), written in Russia.

Additionally, Job’s arguments and lamentation sound not unlike another text from the Apocalypse:

And when he had opened the fifth seal, I saw under the altar the souls of them that were slain for the word of God, and for the testimony which they held: and they cried with a loud voice, saying, “How long, O Lord, holy and true, dost thou not judge and avenge our blood on them that dwell on the earth?” And white robes were given unto every one of them; and it was said unto them, that they should rest yet for a little season, until their fellow-servants also and their brethren, that should be killed as they were, should be fulfilled.

—Rev. 6.9-11

e. they loved not their lives even unto death/did not love their life to the point of death | οὐκ ἠγάπησαν τὴν ψυχὴν αὐτῶν ἄχρι θανάτου [ouk ēgapēsan tēn psüchēn autōn achri thanatou]: The word here translated “life” is ψυχή [psüchē]. It originally referred literally to breath—note that spitting-like sound at the beginning!—and is frequently rendered “soul,” which is how it gave us words with the prefix psych-. There are a few puns in the New Testament about “what a man will give in exchange for his life,” where the everyday not-being-dead-yet meaning is obviously there, but Jesus or the Apostle is obviously urging the hearer or reader to recognize the far greater urgency with which we should look to save our souls.

Footnotes

1That is, not literally griffins, in the sense “eagle-lion hybrid creatures of the sort imagined by Western Europeans”; cherubim “are” griffins only in the sense that, e.g., the Chinese 麒麟 [qilin] “is” a unicorn: a somewhat-similar legendary animal that fills a somewhat similar imaginative niche. Ezekiel and Revelation appear to indicate that the cherubim are to be identified with the tetramorphs, celestial beings described as having four faces (those of an eagle, a human, a lion, and an ox) and wings, which Revelation makes wings full of eyes. It is speculated that cherubim may be related to or derived from the Babylonian idea of lamassu, human-headed, winged bulls considered tutelary or protective spirits.

2The Hebrew form is שַׁמְּחֲזַי [Shammchàzay]; Shemihaza is an Aramaic form, while Samyaza is an adaption to Greek (originally Σεμιαζά—why the epsilon was turned into an a and the iota into a y, instead of being transcribed *Semiaza, I don’t know, unless it was to prevent confusion with the authentically Greek prefix semi-).

3Technically, this would be a mere pun. The old adjective fell meaning “terrible, dire, fearsome” appears to descend from the Proto-Germanic adjective *faluz “cruel, terrifying,” whereas the verb fell with the senses “to cut down; to kill,” though it goes back just as far, comes from the verb *fallijaną “to cause to fall.” As far as I can tell, the consensus reconstruction of these two terms come from quite unrelated Indo-European roots.

4I think so, anyway; my source for this image claims, very incorrectly, that this is a “sixteenth century manuscript,” despite the fact that the writing here is quite obviously a font, so I’m not really confident they’re being quite forthright about what text appears here. (I mean, it’s the right script, but I can only recognize fidäl, I can’t actually read it, and I don’t have a go-to source for texts in Ge’ez, since I’ve never hitherto needed one.)

5An ell (originally meaning an arm’s length, and apparently related to the word “elbow”!) is an archaic measurement sometimes equated with the cubit. (The traditional English ell is 45″, or one and a quarter yards. Other national or regional ells could be as short as 21.5″, less than two feet, or as long as 54″, four and a half feet.) This would place the height of these giants at around 11,250 feet—a little over two miles. Presumably, one of three things is going on here: a) this was never meant to be taken literally; b) the author did not really think through a tale he was inventing from whole cloth; or c) the author heavily embroidered a tale he had received in his retelling. If I knew more about Ethiopic literature, I might hazard a guess about which of these it is, but I don’t, so I won’t.

6The Masoretic Text and St. Jerome’s Vulgate both have a single, unnumbered book of Ezra/Esdras, or Ezra-Nehemiah: so far so good. However, the important Clementine edition of the Vulgate and most English Bibles today split this into the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, or I and II Esdras. The Septuagint, Vetus Latina (“Old Latin,” i.e. the Latin Bible predating Jerome), and Ethiopic versions all contain additional books of Ezra, so they put a number on Ezra-Nehemiah … but not the same number. The Ethiopic Bible makes it I Ezra (fair), while the Septuagint and the Vetus Latina make it II Ezra (what?)—none of which are the II Esdras we’re talking about. Angry yet? Save some up, it only gets worse from there.