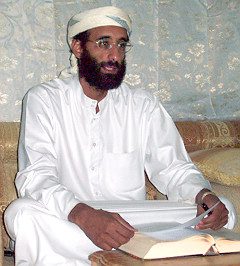

I start with this: Innal illahi wa innal illayhi raji’un – to Allah we belong, and to Him is our eventual Return. I say this because Shaykh Anwar al-Awlaki, who was reportedly killed today in Yemen, was a self-described Muslim.

I start with this: Innal illahi wa innal illayhi raji’un – to Allah we belong, and to Him is our eventual Return. I say this because Shaykh Anwar al-Awlaki, who was reportedly killed today in Yemen, was a self-described Muslim.

The reported death of al-Awlaki has put American Muslims in some unchartered territory – whereas when Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden was finally killed last spring, there was almost universal relief at his death, but with al-Awlaki, the feelings of American Muslims seem to be varied, which is natural given the legacy of al-Awlaki and how it has changed over the years.

These feelings run the gamut of those who believe his death should not be mourned to those who are alarmed that a fellow American Muslim, however radical he was, was targeted and killed without a trial, to those who are having trouble reconciling their experiences with a pre-9/11 al-Awlaki who gave inspiring internet lectures and lessons on Islamic history and the prophets with the “radical Al Qaeda celebrity” who since 9/11 has called for violence against Americans.

As always, it is dangerous to try and speak for an entire population, or be the voice of the “moderate majority” of American Muslims. I don’t profess to do that here. As evidenced in Patheos’ “Three Questions for American Muslims” project this month, the opinions of American Muslims are at times similar, and often varied, as many who took part in the project said that American Muslims are not a monolith, but rather a diverse population with dynamic and varying viewpoints.

The sobering situation we found ourselves in now stems from the trajectory al-Awlaki traveled in his belief system as well as the nature of how al Awlaki was killed. As CNN.com reported, “The transformation from an imam who originally condemned the 9/11 attacks to a key al Qaeda operative took place over a number of years, as the war on terror expanded and as he found himself caught up in it.”

Al-Awlaki, who was born in New Mexico, lived in the U.S. until he was 7, when his family returned to Yemen. He came back to the U.S. in 1991 and completed two degrees. He was an imam in California and Virginia, and according to the 9/11 Commission Report, he “preached to and interacted with three of the 9/11 hijackers.” Following 9/11, he condemned the attacks, but as the war on terror became more complicated and expanded, his role in it grew. His father, Nasser al-Awlaki, told CNN last year that after his son spent 18 months in prison in Yemen on kidnapping charges, “I detected a change … he began to get away from the mainstream.”

During the past five years, al-Awlaki has been connected to several terrorist plots and acts, including:

- Sharing emails with Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan right before the Army psychiatrist went on a rampage and killed 13 soldiers and wounded numerous others at Fort Hood, Texas

- The stabbing of a member of the British Parliament by a 21-year-old British student, who told police she had watched hundreds of hours of al-Awlaki video

- The attempt by Nigerian Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, awaiting trial in the U.S., to detonate explosives sewn into his underwear on Northwest Airlines Flight 253 as it landed in Detroit on Christmas day in 2009.

- Calling for the killing of Americans in a 2010 internet video, saying they were the “party of the devil”

It’s a damning list, and so one might think that there would be a general agreement that the death of Al-Awlaki, seen as an Al Qaeda recruiting and fundraising threat, is a good thing. But there are two things that making this an uneasy situation for many American Muslims – that before al-Awlaki turned towards extremist thinking, his lectures and lessons were indeed beautiful, educational, and explained various aspects of the Islamic faith and about the prophets in a truly (positive) inspiring way; and the nature in which he was killed – without due process.

On al-Maghrib Institute Director Yasir Qadri’s Facebook fan page (which is maintained by his fans and students, not by him), a status update about the killing has begat a litany of comments. One commenter said, “I was surprised to find this on the news this morning. The first EVER lecture I heard was given to me by my son and it was Awlaki’s about the creation of Adam, and I would play it EVERY morning driving the kids to school. We all learned so much from that beautiful CD.”

Another commenter on the thread wrote, “Only Allah knows if the allegations against him are true or not … but his killing is unjust. It’s a great loss. His lectures, especially the life of Muhammad and other sahabas, were phenomenal!”

Still another commenter on the thread had this to say: “Many people have something in common with Imam Awlaki and myself – we have all learned from his CD’s, the very first audio I listened to was Lives of the Prophets (AS), by IMAM ANWAR AWLAKI, and since then I have listened to all his CD’s. We have all learned a lot from this man, Insha’Allah, he continues to reap rewards for the good deeds that many of us perform because of his knowledge which he bestowed upon us. … His lectures are available all over the internet, beautiful and well spoken. … He influenced me in many ways, I have his listened to all his lectures, and I have no desire to ‘kill every American i come across.’”

Aziz Poonawalla wrote on his blog, City of Brass, that “American muslims should at least not mourn his passing. The man was a clear and present danger to our muslim community in America, our “public enemy #1″ who labeled all of us “traitors to the Ummah” for our condemnation of violence and terrorism. The burden we have borne because of the actions of those like Hasan who acted on Awlaki’s urging has been a terrible one, and would have continued had Awlaki remained alive.”

I hear what he is saying, but I think many are having trouble with that. And before there is a rush to judgment by those who feel that nothing less than satisfaction over al-Awlaki’s death is un-American (or somehow implicitly supports terrorism), I want to appeal to humanity – when good and bad are mixed up a person, it’s hard not to have mixed feelings when that person passes.

Perhaps if al-Awlaki had faced a trial instead of being hunted down and killed, then there would be more solid closure on this. But as Glenn Greenwald wrote in his Salon.com column,

“What’s most striking about this is not that the U.S. Government has seized and exercised exactly the power the Fifth Amendment was designed to bar (“No person shall be deprived of life without due process of law”), and did so in a way that almost certainly violates core First Amendment protections (questions that will now never be decided in a court of law). What’s most amazing is that its citizens will not merely refrain from objecting, but will stand and cheer the U.S. Government’s new power to assassinate their fellow citizens, far from any battlefield, literally without a shred of due process from the U.S. Government. Many will celebrate the strong, decisive, Tough President’s ability to eradicate the life of Anwar al-Awlaki — including many who just so righteously condemned those Republican audience members as so terribly barbaric and crass for cheering Governor Perry’s execution of scores of serial murderers and rapists — criminals who were at least given a trial and appeals and the other trappings of due process before being killed.”

Going forward, as American Muslims sort out their feelings, I am reminded of how many this month after the 10th anniversary of the attacks of 9/11 said that a new Muslim narrative must be written, and that we are done condemning every attack committed by so-called “Muslims,” that such Muslims don’t speak for the majority, and we should not have to defend ourselves or our faith all the time. I give big thumbs up to that sentiment.

But the killing of American-born Anwar al-Awlaki, an imam who had a lot of good things to say before he started saying bad things, is a tough one.

Poonawalla writes, “The inevitable debate will rage over his citizenship and whether the Obama Administration was justified in an “extrajudicial killing” without due process. I’m not comfortable with the State having the power to kill, but the argument here is far stronger than that for capital punishment, especially since Awlaki removed himself from the reach of the law by hightailing to Yemen’s backwaters, something no one on Death Row can do. As Awlaki renounced his citizenship, and called on other American muslims to wage war against America, there really should be no debate – the man was a literal traitor to his country, and on this point at least the Constitution is quite clear: Article 3, Section 3 and the landmark Supreme Court ruling of Haupt vs. the United States (1947). “

Poonawalla makes sense, Greenwald makes sense, and the feelings of all those commenters on Qadhi’s Facebook page make sense too. Like I said, it’s a tough one.