The future rewards those who press on. I don’t have time to feel sorry for myself. I don’t have time to complain. I’m going to press on. – President Barack Obama

As I waited for my own fella, I saw the youngster walk out of the school, accompanied by a teacher’s aide. I had seen the child numerous times in the past, in fact just the day before when I had been at D’s school for a parent-teacher conference and a fire alarm drill happened.

That day the child, I’m guessing eight or nine years old in age, was one of the last kids to exit the school building, carefully picking his steps and clutching his luvvies – two stuffed toys and his iPad – to his body. His teacher gently guided him down the stairs. The child stepped down one foot, then another meeting the first on a step. Repeat.

Slowly.

Carefully.

Wobbly.

Today he came out of the school to the carline the same way — clutching his toys, harness zipped over his chest (to secure him in his seat and falling down off of one shoulder. I’m guessing without it he would move around in the car. D wore one himself on the bus for years.)

His aide gently guided him to the van waiting for him and climbed in after the child to help secure him in his seat.

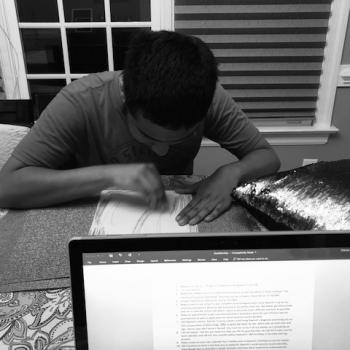

By this point D was already seated in my car. Now a strapping young 16-year-old man, D needed no help getting into our car. He, too, came out accompanied by a teacher’s aide. All the children in his autism school are accompanied by teachers or teacher’s aides to their designated car or bus.

D was strong, confident and loud, spinning his beads and putting his own seatbelt on. No more harnesses were needed, no more seatbelt locks. It is the smallest of accomplishments amidst a sea of choppy waters. But it’s one I fiercely cherish.

Because as I watched the other child, so hesitant and fragile looking, a wave of memories rushed over me: D as a three-year-old, the first time I had him ride the bus to his autism preschool in New York City, him wailing and crying, me crying as well for full month before he accepted the new mode of transportation and separation from his mother.

D at age seven, when we transitioned him from his private autism school to public school, and he started riding the bus again at a God-awful early time of day after I had been driving him for two years. That harness zipped over his chest, slipping off of one shoulder.

D at age 11, finishing his fifth year in public school, the year of Autism Hell, as we call it, when he was engaged in the throes of self-injurious behavior, crippling anxiety, nonstop crying and a host of other heartbreaking issues that his teachers just could not safely handle.

D at age 12, transitioned back to the private autism school, where for the next two years he still would still engage in all the self-harming and other soul-crushing behaviors as we desperately worked to figure out what he was trying to tell us, what he was feeling and what he ultimately needed. All this leading to an utterly tragic turn of events in his life from which he has emerged strong and adjusted, while I continue to falter and fall to this day.

And D now – tall (taller than me), strong, struggling with an entirely new set of things but also having moved past that hesitant, fragile-looking stage of his life.

I’ve spent the better part of last year worried and thinking about D’s future. Thinking about Autism Adulthood, thinking about how without the cuteness and “free pass” of youth, D is quite accountable in the public eye for whatever things he may or may not do. Thinking about how to plan for his future in a post-secondary world. Thinking how I could stop time.

But in the car today, watching the other child with my own tears tumbling down, I realized what D has known along: Moving forward is much better living in an endless loop or longing for the past. Though I can’t proclaim to know exactly what he is thinking, I’d wager that he would rather face his future then spin his wheels where he is.

So must I.