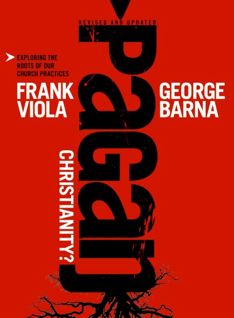

I just finished studying Frank Viola’s and George Barna’s recent book, Pagan Christianity: Exploring the Roots of Our Church Practices. I want to start to say what I appreciate about the book and finish with what I think are some concerns.

I just finished studying Frank Viola’s and George Barna’s recent book, Pagan Christianity: Exploring the Roots of Our Church Practices. I want to start to say what I appreciate about the book and finish with what I think are some concerns.

Reading this book reminded me of the hours of ambitious dreaming and passionate debates that occurred during my bible college and seminary days with other visionary young radicals. It evoked the intensity with which I first went into the pastoral ministry, like a bull in a china shop, like Jesus with a woven whip into the den of thieves. In other words, I agree with almost everything they say. I have a problem with churches owning so much money, property and buildings; I question liturgy and orders of worship; I struggle with the one-man monologue sermon model; I have always wrestled with “full-time paid ministry” pastor positions; I disregard Sunday dress; I don’t like the control of worship music by a select and talented few; I don’t believe in tithing; I question the sacraments, formal Christian education, and our whole approach to the New Testament. In short, I too kick against the system. So, if you want to get an idea of what the authors insist are the pagan roots of most of our religious practices and compare them to the New Testament and early Church, get this book. With the plentiful footnotes and bibliography, it’ll give you enough to study.

But I have some concerns. Even before I got to the substance of the book, I read a line in the forward that concerned me. The following, they say, is their “proposal“:

the church in its contemporary, institutional form has neither a biblical nor a historical right to exist (p. xx).

This reminded me of something I read in Sam Harris’ book, The End of Faith… something to the effect that religion, or faith at all, has no right to exist. In his opinion faith has no grounds for being. It must and will become as obsolete as alchemy (p. 14). Therefore it should be purged from the earth, to the point that in the future adherents to a religious faith of any kind must suffer shame. When I read Harris’ book I immediately felt that, given any authority or legislative power, this would lead to some form of religiocide. Same with Pagan Christianity: such thinking, linked with power, will lead to, I don’t know… denominatiocide? I agree: anything that impedes human freedom and builds barriers between humanity and God must be challenged. But it feels dangerous to suggest that, as Viola and Barna do, “beyond dispute“:

that those who have left the fold of institutional Christianity to become part of an organic church have a historical right to exist– since history demonstrates that many practices of the institutional church are not rooted in Scripture (p. xxi)

I was infant-baptized in the Anglican communion, came to faith in the Baptist church, got baptized again, switched to Pentecostal, “got the Spirit”, drifted into Interdenominational, stopped going, joined a New Testamentish house-church style of community, changed to Presbyterian, received spiritual direction in the Roman Catholic church, and am presently a Vineyard pastor. I’m not willing to point my finger at any one of these denominations and pronounce: “You have no biblical or historical right to exist!” Conversely, I will not point my finger at any house church, emergent movement, or any other gathering that seems to look more like a New Testament church and declare: “You have the biblical and historical right to exist!” And I will tell you why.

Whereever we go, there we are. I’ve discovered that no matter how radical I become, no matter how much I try to look like the New Testament Christian, no matter how closely resembling the early church we might appear, it is all shot through with humanity, history, and heresy. The book doesn’t take into consideration the phenomenon that when two or three are gathered together in Jesus’ name not only is the Lord there, but there are also the principalities and powers. A new creature is formed when people collect for any common purpose, goal, vision, value, etc., etc.. No matter how radical and revisionist or restorationist the community is, the powers that would attempt to dehumanize us, oppress us or bind us are very real and active… just as real and active as in our most ancient denominations, churches and traditions. To make the extraordinary claim that the early church “understood God’s passion for His church, they lived it out” (p. 246) is therefore arguable. When I read between the lines of the New Testament, I see, along with the good, a very chaotic community that struggled with the same issues the contemporary church struggles with: ambition, power, position, money, possessions, charismata and worship, order, heresy, dress, the abuse of the sacraments, teaching, and so on. I’ve aborted the attempts and even the desire to return to a New Testament model of church. I don’t think we can know for certain what it was really like. And if we did, I think we’d uncover a very unattractive, sordid and sometimes repulsive mess.

Viola and Barna suggest that Jesus came as a “Revolutionary, tearing apart the old wineskin with a view to bringing in the new” (p. 246). My take on that parable is that when the new enters the old, the old simply cannot hold it. It will fall apart. And I think this is exactly what Jesus does: he simply enters our world, like a computer virus, and our systems, traditions, beliefs, theologies, practices, religion, spirituality… everything!… slowly, or rapidly, begin to unravel. They cannot hold him. He came as a free man within the system, but not part of it. He was an observant Jew and Rabbi… except when he wasn’t. And he wasn’t precisely when our liberation was at stake. And this, it seems to me, is the best way to be… personally and corporately. It would be irrational of me to lightly dismiss all human and historical developments as illegitimate. It would be naive of me to attempt to return to the New Testament style of doing church. There is something more important to do no matter what ideology, faith, religion or tradition we find ourselves in. What I’ve decided to do is live freely myself while challenge all ideas, beliefs, traditions, powers and systems that threaten the well-being and liberty of all people everywhere.