Hospice Chaplain here, bringing my UU-Pagan perspective to the support of human beings approaching their own deaths, or the deaths of their beloveds, in the context of their belief systems and practices no matter what they are. This month I’ve supported Muslims, Protestants, Evangelical Christians, Jews, Wiccans, and people who say that are ‘not religious’.

This month I’ve been noticing the many ways we humans try to protect ourselves from whatever terrifies us, even when what that is changes from moment to moment.

Are we afraid of dying? Are we afraid of living ‘like this’ (whatever ‘like this’ means to the particular patient)?

Are we afraid of our beloved relative living ‘too long’ ‘like this’ (whatever that means, exactly)? Are we afraid of our beloved dying? Leaving us by some other means on the way to death?

Denial

One way we protect ourselves is through Denial. The joke these days goes ‘Denial is not just a river in Egypt.’ We like to pretend that denial is something that happens to other people – we ourselves are, of course, too level-headed for that.

Earlier this month I sat with a patient and thought there would be weeks left, if not months. I was enjoying our ongoing conversation, even within the limitations of the patient’s declining ability to speak. As I left one afternoon, I thought to say something about how much I enjoyed visiting and getting to know this patient. I didn’t know it would be my last visit. I didn’t know I was in denial about that patient’s condition until that patient was no more. I thought there was more time.

Overwhelmingly this is the most frequent response of families and staff alike, when a patient dies. How is it that we can look at cachexia (“ka-KEX-ee-ya,” meaning ‘wasting away to skin and bones’) and not realize time is short? How is it that we can watch and listen to labored breathing and not understand that this can’t go on, and it won’t? Even the nurse who says ‘I don’t think this patient would survive the ambulance ride’ can be surprised when that patient dies before the ambulance arrives.

Why is denial so tempting?

Partly, we want to believe that what we want to be true, will actually be true. Some of us bounce back and forth between our dread of the worst outcome, and our fear that we’ll be found foolish for worrying, later, if it doesn’t happen. Some of us have so much anxiety that we can’t actually see what is right in front of our eyes.

In the hospital, in the context of acute life-threatening illness, there’s a tendency to ‘try something else’ if the first few treatments don’t change the situation. We’ve put in so much time / effort / money / emotion already, what’s one more? What if the ‘one more’ would be the thing that would solve the problem? How would we feel if we didn’t try?

In the hospital, in the context of acute life-threatening illness, there’s a tendency to ‘try something else’ if the first few treatments don’t change the situation. We’ve put in so much time / effort / money / emotion already, what’s one more? What if the ‘one more’ would be the thing that would solve the problem? How would we feel if we didn’t try?

The family loves the patient (or anyhow feels they ought to), so how could we not try ‘everything we can’ to save them? The medical staff values the family’s good opinion … ditto. Maybe that next thing is a rickety bridge to an unknown future, but surely it’s worth the risk. ‘Don’t just stand there: DO something!’

That’s the kind of thinking that leads to the medical juggernaut of progressively more and more aggressive treatment. Sometimes this occurs in a series of unexpected events – surgery discloses more than could be found by imaging, say, or one complication leads to more treatment, which leads to another complication. Sometimes this occurs because a situation that might have been seen as End of Life is somehow diagnosed as ‘something treatable’. Often it’s both, by turns.

In the home care setting, in the context of terminal illness or longterm progressive illness, we want to avoid suffering – that is, we want to avoid having the patient suffer, and also (let’s be honest) we want to avoid the pain of watching the patient suffer. (This is often true of both families and staff). There are trade-offs here, for the patient: which is worse, having pain or feeling ‘loopy’? Which is worse, eating mushy food or risking choking?

What do we do – what should we do – when patient and family disagree? What if the patient can no longer say what the patient wants? What if the patient believes themself competent and able to make their needs known, but the family disagrees? There are trade-offs here, too, for the family: which is worse, letting the patient have their way (even if foolish or dangerous), or taking away their last shred of autonomy? Which is worse, taking the advice of family and friends (even if it disagrees with medical advice) or stubbornly sticking to a failed plan?

Everywhere in medicine today there are questions about ‘Who Decides?’

Who decides whether the patient ‘needs’ to be sedated or not? Who decides whether the patient ‘has to’ change their diet, or stop driving, or even stop smoking? Under what circumstances does the patient lose the right to make their own decisions? Under what circumstances should a medical person overrule a patient or family member (or do any such circumstances exist?).

Lots of us would like to imagine that we will know when it’s time to stop aggressive treatment. Even those of us who work in Hospice aren’t always good at making those decisions for ourselves.

What are we afraid of?

Pain, of course. Which is worse, physical pain or emotional pain? For most people the answer is: It depends. So how can we know in advance?

This is the point where I’d love to give you a cookbook answer: I’d like to say, You know in advance by doing this, and then doing that, and answering this questionand then that one. Here’s a decision tree to help you figure it out. Here are the people and Beings you should consult and then you’ll know. But …

Hospice Chaplain here. I wish I knew how to know in advance. All I can really tell you is, we all do the best we can with the information we have, the experiences that came before this, and our hopes and fears.

Each of us now on planet was born, sometime, in some place. Each of us now on planet will one day die, sometime, in some place. And a lot of us will be anxious about it as we get close to it, or as our loved ones do.

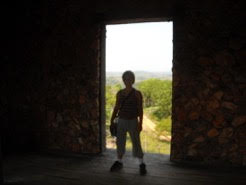

There is no way to do it perfectly. There is often less anxiety when we can accept that fact. The door is always open; one day, each of us will step through.

Blessed Be.

–Maggie Beaumont

American Memorial Day