The first in an important new series of books on Anglicanism has appeared: Reformation Anglicanism: A Vision for Today’s Global Communion (Crossway, 2017). This volume, which leads a projected series of six, features chapters by globally-recognized scholars and leaders such as Michael Nazir-Ali, Ashley Null, and Ben Kwashi.

The first in an important new series of books on Anglicanism has appeared: Reformation Anglicanism: A Vision for Today’s Global Communion (Crossway, 2017). This volume, which leads a projected series of six, features chapters by globally-recognized scholars and leaders such as Michael Nazir-Ali, Ashley Null, and Ben Kwashi.

I will treat each of the seven chapters in the next few blogposts. So stay tuned.

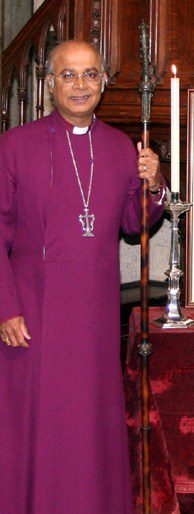

The first chapter, “How the Anglican Communion Began and Where It Is Going,” is by Dr Michael Nazir-Ali, formerly Bishop of Rochester, England and now the President of the Oxford Centre for Training, Research, Advocacy and Dialogue. Nazir-Ali was a leading candidate for the Archbishop of Canterbury position when Rowan Williams resigned from the post, and many have lamented his being passed over. Nazir-Ali, who is of Pakistani descent, might have averted the current division in the Communion by virtue of his theological clarity and courage.

Let me sketch highlights of Nazir-Ali’s chapter and then reflect on the question above.

Nazir-Ali notes that when native Briton Saint Alban was martyred in the 3rd century, the Christian Church had already been there for some time, planted perhaps by soldiers who had been sent to the island by the Roman Empire or by what we would call Christian businessmen supplying material needs for the Empire.

Pope Gregory the Great sent Augustine of Canterbury in 597 AD, sparking the emergence of an Anglo-Saxon Christianity throughout England. Celtic Christianity vied with Roman Christianity until the Council of Whitby in 664 AD when the Roman way prevailed.

The English Church’s resistance to Rome began long before the sixteenth century. Parliament’s Praemunire law in 1392 prevented outside powers like Rome from interfering in the English Church.

Oxford philosopher John Wycliffe (1320-1384) called for the final authority of Scripture and denounced transubstantiation.In other words, the Church of England had already assumed a distinctive character before the 16th century. This has been noted in more detail by Martin Thornton in his English Spirituality (Wipf and Stock).

Nazir-Ali writes that Reformation Anglicanism was generally uninterested in world mission, like other Reformation churches in the 16th But this changed in the 18th century, when the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK) ordained the first African, Philip Quaque, in 1765. The Church Missionary Society (CMS) was founded in 1799 as a result of the evangelical revival in the Church of England, led by the preaching of John Wesley and George Whitefield.

Anglicanism became a worldwide communion as a result of three factors, according to Nazir-Ali. First, it spread “coincidentally” as English-speaking peoples moved to the Americas, the Caribbean, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific. “As these people went to new lands, they took their church with them.”

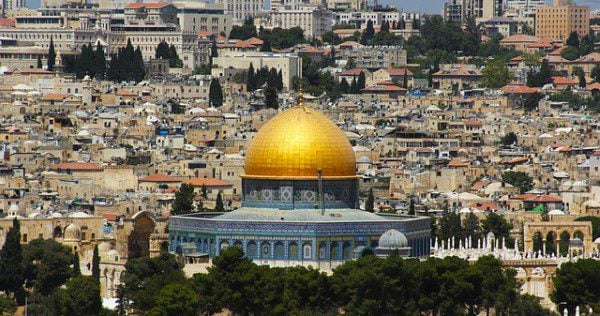

Second, the evangelical revival started mission societies such as the CMS and the Church’s Ministry among the Jewish People (CMJ).

Third, Anglican Catholic missions like the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG) and the Universities Missions to Central Africa spread their version of Anglicanism focused on church order as well as conversion. They were also insistent that the Church should be free of state interference. Nazir-Ali says they were “suspicious” and “even hostile to the establishment of the Church of England as the official state religion.”

Anglicanism has always had a prophetic edge that gave room for dissent. Nazir-Ali points to high church Anglicans who wanted to distance the Church from government, Anselm’s “insistence that Henry I should take an oath to maintain the liberties of his subjects,” AB of Canterbury Stephen Langton’s pressing King John to uphold the Magna Carta, martyrdoms on both sides of the Reformation in the 16th century, Non-Jurors who were deprived of their sees and livings under William and Mary, and the Anglican Province of South Africa’s resistance to apartheid.

Nazir-Ali notes that Anglican ecclesiology follows (2nd-century) Ignatius’ emphasis on bishops and (3rd-century) Cyprian’s stress on proper autonomy of provinces while rejecting Cyprian’s view that the see of Rome is the principal means of establishing communion.

The former bishop observes that while recent structures like the ACC and Lambeth Conferences have failed to provide doctrinal and ecclesial unity, the Global Anglican Future Conference (GAFCON) and the Catholic Anglican organization Forward in Faith provide the best hopes for future Anglican unity in orthodoxy.

The renewal of Anglicanism, Nazir-Ali argues, “will come about not through the reform of structures . . . but through movements raised up by God.” They will plant churches, renew worship, and campaign for the poor and persecuted.

In sum, Nazir-Ali’s excellent chapter shows 1) that the Church of England started long before the 16th century, 2) has become a worldwide communion because of evangelical and high church missions, and 3) has the promise of fresh reformation and renewal.