In this year of the 500th anniversary of the beginning of the Reformation, legions of commentators are talking about what started and sustained the Protestant Reformation. I say “Protestant” because the Catholics had their own Reformation, partly in response to the rise of Protestantism, in their Council of Trent (1545-63).

In this year of the 500th anniversary of the beginning of the Reformation, legions of commentators are talking about what started and sustained the Protestant Reformation. I say “Protestant” because the Catholics had their own Reformation, partly in response to the rise of Protestantism, in their Council of Trent (1545-63).

Among the most important slogans of the Protestant Reformation was sola scriptura, which means “by Scripture alone.” By this phrase Luther, Calvin, Zwingli, and Cranmer meant that our final authority for what we believe and do should be God’s Word rather than (merely) men’s (using the male pronoun in an inclusive sense for both men and women) words.

At stake back then (and indeed Cranmer and others went to the stake over this) was the meaning and role of tradition. The Catholic Church was saying in the late Middle Ages that its understanding of the Bible was the proper one, and therefore that Christians should use Catholic tradition to interpret the Bible.

Was this a conflict over whose words were authoritative—God’s or man’s? Catholics said No, for they believed that the Holy Spirit had guided the Church in its gradually unfolding understanding of the Bible. So they believed that Catholic tradition (which they call the magisterium, from the Latin word magister or teacher) was God’s Word too, or more strictly, Spirit-inspired men’s words interpreting the Bible.

But there was a huge problem for the Protestant Reformers. In the 14th and 15th centuries, Roman Catholic theology had veered off course on the question of salvation. It had started teaching semi-Pelagianism, which both Catholics and Protestants now agree is the unbiblical idea that we start the process of being saved which God then completes. So the Reformers had this more recent and false tradition in mind when they cried Sola scriptura! Our final authority for knowing how to be saved is not church tradition but God’s Word (the Bible) alone, which teaches that we cannot start the process of being saved because we were dead in our sins before the grace of God gave us new life.

John Yates III tells the story of how the English reformers, especially Thomas Cranmer, thought through this problem of authority in the third chapter of Reformation Anglicanism: A Vision for Today’s Global Communion (Crossway, 2017). They concluded that Scripture is sufficient for understanding how to be saved and that it teaches clearly that God alone can wake us up out of our sin. We are helpless until God comes to us.

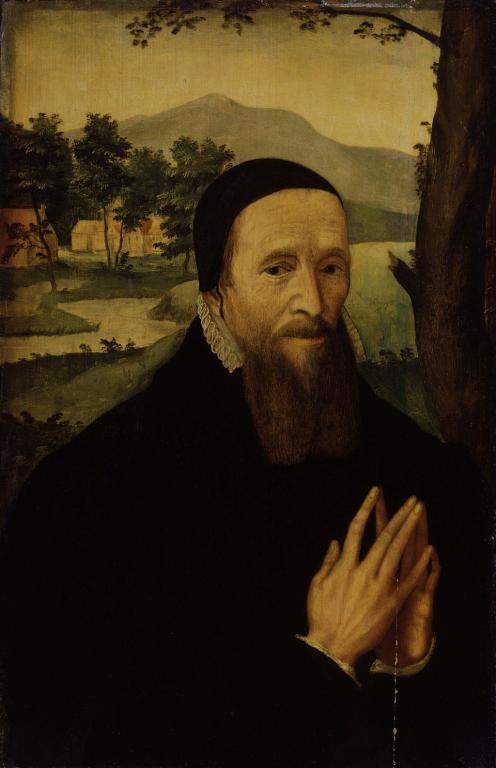

On the question of authority, Anglicans have sometimes used what they claimed to be Richard Hooker’s image of a three-legged stool whose legs are Scripture, reason, and tradition (see Hooker’s portrait above). While liberal Anglicans have suggested that Hooker’s three legs were of equal length, Yates points out that Ashley Null’s image of a garden shows otherwise:

“[I]t is far more accurate to speak of Scripture as a garden bed in which reason and tradition are tools used to tend the soil, unlock its nutrients and bring forth the beauty within it.”

This, say Yates and Null, shows the role which Anglican reformers Cranmer and Hooker gave to Scripture. In Yates’ words, Scripture for them was sufficient, powerful, satisfying, and authoritative. It “has the power, in the hands of the Spirit, to reconfigure our hardware, not just our software. . . . Regular exposure to scripture works to change our most basic desires.”

This was part of the genius of the English reformation. Its liturgy, which is widely regarded as the most beautiful worship in the English language, became “a mechanism for Scripture reading, reflecting, singing and memorizing.” Its lectionary exposed English churchgoers to most of the Bible over the course of its one- or two-year daily prayer readings.

So what about tradition? Hooker esteemed the Fathers, and read the Bible at their feet. His point seemed to be that the right tradition is necessary to understand the Bible rightly. But when it comes to bad tradition that misinterprets the Bible’s plain sense, we must choose the Bible alone.