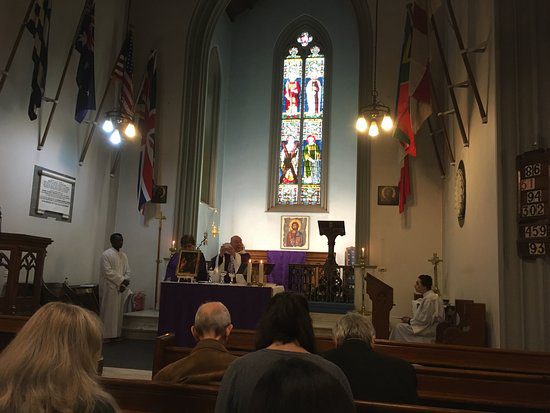

Anglicans are famous for their “liturgical” worship. Generally, this means following set prayers and ways of praying, such as reciting a prescribed confession and one of the ancient creeds. Not to mention following a prescribed way of celebrating the sacraments, especially Holy Communion every week or day.

Liturgy: The Work of the People

The word “liturgy” comes from a Greek word which means “the work of the people.” In this ancient custom of worship, worshipers become as a group of Christians what they cannot be as individuals—the people of God.

The people in the pews participate in worship through song and response and join with the priests and deacons in confession and prayer and worship. In what are called non-liturgical churches, all the action is up front, and the people watching are doing just that—being spectators, not participants.

This is why liturgy is called the “work of the people.”

The liturgy was the ancient prayer of the church. Worshipers thought of it as a journey or procession, picking up each Lord’s Day to resume their journey out of the world and into the Kingdom of God—into the fourth dimension, if you will. It is not an escape from the world, but a way to see the reality of the world from a heavenly vantage point.

Liturgy’s Jewish Heritage

The early church did not make up this liturgy from scratch. They derived most of it from theJewish liturgy and brought out its messianic meanings.

So, for example, there was an entrance rite in the Temple liturgies, based on Ps 122.1, “I was glad when they said to me, ‘Let us go up to the house of the Lord.’” The Levite singers would go in a procession before the priests, who would bring up the ark of the covenant (before the temple was built), which contained the two tablets of God’s words and the manna that God fed them with in the wilderness.

The two basic parts of the Christian liturgy—the liturgy of the Word and the liturgy of the Table—are based ultimately on these two features of Jewish history and worship.

God-given prayer

But let’s go a bit deeper into this mystery of liturgy. We could say that it is an answer to the disciples’ request of Jesus, “Lord teach us to pray.” It is behind Paul’s statement in Romans 8, “We do not know how to pray as we ought.”

It helps explain why God struck down Nadab and Abihu when they offered unholy fire (Lev 10). They thought they could figure out on their own how to worship–rather than recognizing that God had already given precise instruction on how Israel was to worship.

Participation in the Son’s adoration

There is a Christological dimension to liturgy. It is worship that joins in Christ’s worship of His Father. The church fathers taught that liturgy is our participation with Christ in his offering himself and his Body to the Father in adoration. It is joining with the saints and angels in their celestial worship.

This worship fulfills the purpose of the creation. In other words, the purpose of the world and worship are the same—that God might be “all in all” (1 Cor 15.28). The key to understanding what that means is to see that the heart of worship is sacrifice, which is the surrender of what is precious to us. When we surrender that, God sets it apart and fills it with his blessing. Then what God sets apart becomes holy. For “sacrifice” means (Latin sacer + facere) “to make holy,” and holy in Hebrew means “set apart.”

This is best seen in the liturgy of the Eucharist. We worship the Triune God, who in the Father gave up the Son to be sacrificed by the Spirit, to make us holy and to bring all the cosmos into the holy realm under the lordship of Christ and the Father. In the sacred meal of weekly (or daily) liturgical worship, we join in the sacrificial offering which the Son makes to the Father, and we pray that others be joined to that sacrifice, so that we and they might be filled with God’s life, and God will be all in all.

As we see God in that offering of the Son, we see God for who he is in his beauty and glory, and we are drawn into him and his Son by the Spirit.

Liturgy & Time

Liturgy is not just for Sunday morning but for the whole week. Each day Anglicans use liturgies for Morning and Evening Prayer. They join with other Anglicans all across the world reading the same passages of Scripture and joining in the same prayers. Then the solitary Anglican in her prayer closet joins thousands (sometimes millions) of others listening to the same Word and praying with the same words.

The church year has come down from the ancient and medieval church. It takes Anglicans through the great seasons of Christian life every year—seasons that re-present to us the whole history of Israel and Jesus Christ.

The most important days and seasons of the church year are:

- Advent,

- Christmastide(12 days),

- Epiphany,

- Transfiguration Sunday,

- Ash Wednesday,

- Lent,

- Passion week,

- Eastertide (seven weeks)

- Pentecost,

- Reformation Sunday,

- Christ the King Sunday.

The result of following the church year is that every Sunday is different, in its readings and prayers, which means not only that Anglican worship is varied each week but also that they are helped to rediscover a new aspect of the Tri-personal God and his history with his people every week and in each new season.

Liturgy & Candles

One of many distinctive aspects of liturgical worship is candles. Candles are lit on the altar before the service as a symbol of Christ as the light of the world (John 8.12), and a sign that Christ is now present in a special way—speaking through the reading of the Word and preaching on it, and feeding us through the sacrament.

During the Easter season and at baptisms and funerals, the tall Paschal Candle is lit as a symbol of the resurrection of Christ.

Liturgy & Music

Luther said music was the greatest gift of God after theology. The historic church has always made music central to worship, recognizing that music is used by God to lift prayer and praise to a higher level.

The Psalms, which have always been the prayer book of Israel and the church, were set to music by David and other Israelite worship leaders, and have been used for musical worship throughout the 2000-year history of the church.

The Anglican tradition has always been known for its splendid musical worship, using classic hymns from the early and medieval Church, as well as Reformation and later Anglican hymns.

All is all, then, the liturgy is a gift from Israel and the historic church that teaches us how to worship the Tri-personal God. It leads us to experience him more deeply as we follow its lead through the church year.