Ben Kwashi’s new book, Evangelism and Mission, ought to be studied by every Christian seminarian wondering about his or her future. He proposes that God is on mission, and that the future of every Christian minister ought to be about joining God’s mission.

Ben Kwashi’s new book, Evangelism and Mission, ought to be studied by every Christian seminarian wondering about his or her future. He proposes that God is on mission, and that the future of every Christian minister ought to be about joining God’s mission.

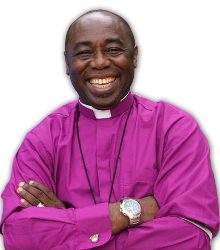

Kwashi is the Anglican Archbishop of Jos, Nigeria, which is right in the middle of a ferocious Muslim persecution of God’s church. Since January of 2018 more than six thousand Nigerian Christians have been massacred by radical Muslims. Kwashi himself has been attacked three times. On one of those occasions, his wife was sexually assaulted and left half-dead.

Kwashi insists that the only way for a Christian to understand the ways of God in this world is to put himself into a place where he has to be radically dependent on God. He sends all his clergy into remote villages of Nigeria for two weeks. They are to evangelize, make disiciples, and start a church that is “able to stand when you leave.”

He tells his clergy not to go with a car or bicycle, or to take any money more than they will need for public transport. “You are on a venture of faith, and God will meet your needs according to his riches and glory.”

The result has been revival. These clergy have seen God provide for them in miraculous ways. Their faith has mushroomed, and they have passed their faith to thousands. Forty-three new Anglican churches have been planted in the Jos area alone (about one million people) in the last 23 years, and scores more elsewhere. Nigeria is now the center of the new Christianity of the global South, the new center of gravity for the worldwide Church.

Mission requires us to believe, says Kwashi, that God will work through us. He tells the story of Ward 3, “a highly respected drinking parlor” in Kwalinga in a neighboring state of Nigeria. The area was famous for 24-hour bars where alcohol and other chemicals were abused. Kwashi was invited to speak in a church next door with 5000 people in attendance. Loudpseakers transmitted his sermons to everyone at the nearby bars. One day that week a young leader of a gang came to Kwashi to say that “we cannot come to the gatherings because we are not good enough,” so “could you, sir, please meet with us separately?”

The gang leader’s followers numbered 96, and they met with Kwashi at 7 in the morning. Twenty-seven were baptized that morning. The 96 started a church that is now thriving with 300 members, several of whom are now ordained and in ministry. I met one of them when I was in Nigeria two weeks ago.

Kwashi and his flocks are being attacked by Muslims. While I was there, his beloved neighbor was shot dead while trying to protect Kwashi. Yet the Archbishop, who grew up with Muslims as friends in northern Nigeria, counsels all on mission to love their enemies. “People of other faiths are human beings created in the image of God and thus worthy both of our love and of hearing the gospel message.” He advises readers that Muslims must pay a very high price for becoming Christians. “We need to ask whether our lifestyle reflects the love of Christ and his righteousness.”

The Archbishop advises his readers to have a plan for mission. This comes, he writes, only by revelation. And that revelation is the key to developing a strategy. One must seek God in prayer, and listen for God to show the way forward. “A person so convicted and focused on this revelation will think through the revelation, dream of how to accomplish the revelation, design a plan for action, follow through this God-given revelation, and soak everything and everyone in prayer.” Without such a revelation, “there will be activities without results, routine of religion without results, and the environment and the people will be blamed and branded as difficult, if not impossible.”

But mature leaders are able to seek a revelation from the Lord. This is why Kwashi never asks for volunteers. Neither did Jesus, he writes. “He watched and waited and prayed, and at the right time, he simply fished out the ones whom he believed to be God’s choice.”

Kwashi says that true leaders are those who have been tested. They have had a wilderness experience like Moses, are willing to be servants washing feet or doing menial jobs, and they know how to listen to people. They are not always eager to talk.

These tested leaders are also willing to begin where they are. “The disciples were told to begin in Jerusalem, that is, in the city where they already were. After that they would gradually move out” but the starting point “was the home base.”

This book is not for the faint of heart. Kwashi is blunt. “Whoever refuses to participate in evangelism is not only disobedient, but is actually guilty of wishing the world to be condemned.”

Perhaps this is why the church in Nigeria is growing even under persecution. There is a sense of urgency in this book and its author that is rare in the United States.

Have we become complacent? Have we lost—if we ever had it at all—what we see among the apostles in the Book of Acts, an urgency to reach the lost?

Kwashi is adamant that today’s Africa not make the mistake which early Africa made. “The North African churches of the early centuries were Roman imports who never reached out to the local people in the surrounding areas. . . . the churches were often ethnic ‘social clubs.’” This is why, he claims, North Africa fell so quickly to Islam in the seventh century.

The alternative, Kwashi writes, is to fulfill the Great Commission (Matt 28:18-20) with boldness.

This is a book for the church of this new century. It will be a manual of action for millions of Christians who struggle to find a way forward when their culture is turning against orthodox Christianity.