Earlier this week, friend and fellow Patheos blogger Dave Armstrong published a blog entry Martin Luther vs. Nestorius Regarding “Mother of God”. Now Dave is a Catholic apologist. So of course he presents Nestorius in somewhat of a negative light. Dave does so to appeal to Martin Luther’s refutation of a position held by many Protestants today–today’s Protestants being the spiritual heirs of Martin Luther’s Reformation.

Earlier this week, friend and fellow Patheos blogger Dave Armstrong published a blog entry Martin Luther vs. Nestorius Regarding “Mother of God”. Now Dave is a Catholic apologist. So of course he presents Nestorius in somewhat of a negative light. Dave does so to appeal to Martin Luther’s refutation of a position held by many Protestants today–today’s Protestants being the spiritual heirs of Martin Luther’s Reformation.

Yet what about our brothers and sisters in Christ who are heirs to the teachings and spiritual leadership of Patriarch Nestorius? Many Christians in the west are unaware they still exist today as the Assyrian Church of the East and the Ancient Church of the East, and that theirs is one of the most persecuted Churches in the name of Christ. Thus Dave’s recent blog was the catalyst for my wanting to share my own first encounter with these brothers and sisters whose history since apostolic times includes Patriarch Nestorius. Their history also includes suffering intense persecution for the name of Christ (over 40 million martyrs by the 10th Century). This is not to mention what the death, torture and displacement suffered in the last two decades as Middle Eastern Christians. Thus it is truly fitting that my thoughts turn to them today on Good Friday–a day when Christians contemplate Christ’s crucifixion and death.

A FIRST ENCOUNTER WITH ASSYRIAN CHRISTIANITY

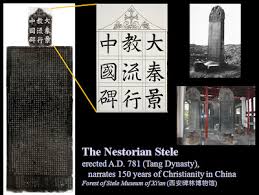

My curiosity was piqued. From the moment I was first introduced to the Assyrian Church of the East, I was fascinated to learn they were once the largest church geographically—spanning all the way up into China and Mongolia–and likely the largest Christian Church demographically as well.

My curiosity was piqued. From the moment I was first introduced to the Assyrian Church of the East, I was fascinated to learn they were once the largest church geographically—spanning all the way up into China and Mongolia–and likely the largest Christian Church demographically as well.

To me this raised the question: Why do Christians in the West know so little about them today? Including Eastern Christians like myself? Who are these Christian brothers and sisters, established during apostolic times, who have suffered so much persecution and martyrdom throughout their history? Why is the symbol of the cross so important to them? So important, in fact, that they consider it a sacrament. Are they in fact Nestorian as many claim? These and other questions gripped my imagination in the weeks that followed.

Therefore, when asked to choose an Eastern Christian Church to visit and research as a topic for a course I was taking through the Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky Institute of Eastern Christian Studies, the Assyrian Church of the East seemed a natural choice. Of course my options were limited as a Ukrainian Catholic. As per the course instructions, excluded were other Eastern Catholic Churches sui iuris with whom my Church shares full communion. Also excluded was any Eastern Orthodox Church since Eastern Orthodoxy shares the same Byzantine liturgical and spiritual patrimony as the Church to which I belong. My only other option within reasonable driving distance was one of several churches belonging to the Oriental Orthodox communion.

Prior to taking this course I had not even been aware that the so-called Nestorian Church was still existence. Thus having prayed and reflected upon my choices, I felt drawn to visit to the Assyrian Church of the East. What I did not realize at the time is that by the end of this course, my encounter with the Assyrian Church, which began as a class assignment, would morph into an ecumenical encounter between local religious leaders and the religious leader of Canada’s Assyrian diaspora.

FINDING MY WAY

My first hurdle was finding the nearest Assyrian church. I visited several international Assyrian Church of the East websites. The closest Assryian church to me was The Cathedral Church of Saint Mary in Toronto. The listing provided a mailing address, telephone number and the names of two parish priests. I called the number and left a message.

FIRST CONTACT

The next day, while having coffee with friends, I felt my Blackberry vibrating in my pocket. Noticing “Assyrian Church of Canada” on the caller ID, I excused myself from coffee and answered the call. The accented voice on the other end introduced himself as Fr. Audisho.

Father was a priest with the Assyrian cathedral in Toronto, and he had just received my voice message. Would I like to visit the cathedral for Holy Qurbana this upcoming Sunday? He said Qurbana was at 9 a.m. Because I had duties at our parish that weekend, I explained it would not be possible for me to venture too far from home Sunday morning. “Would the following Sunday be possible?” I asked.

“Yes,” Father said. “The bishop will be back then. Perhaps I can arrange for you to meet him after Qurbana and ask him some questions.” Because Fr. Audisho would be absent that weekend, he promised to leave a copy of their order of service with Fr. Yousif Sermez, the other priest at the cathedral. Qurbana, Father explained, was the name by which the Assyrian Church of the East referred to their Eucharistic liturgy. What we Byzantine Catholics refer call Divine Liturgy, and our Roman Catholic brothers and sisters refer to as Holy Mass.

The order of service contained their liturgy in Assyrian, English translation and English transliteration. Simply show up ten minutes early, introduce myself to Fr. Yousif, and he would pass me a copy as well as introduce me to the bishop and members of the community after the service. The call ended with me thanking Fr. Audisho for his help and mentioning that I would likely bring some of my children with me in order to share in this experience. He replied that my family would be most welcome to visit too. Additionally, I was welcome to take photos.

MEETING AND PRAYING WITH THE COMMUNITY

On Sunday, October 27, my wife Sonya and I woke our five children at 6 a.m. I had only planned on taking our three oldest—ages twelve, ten and seven—however, before going to bed the previous evening, Sonya mentioned that she too would like to experience Sunday worship with the Assyrian Church of the East. Therefore by 7:15 a.m. our mini-van was packed and on the road, headed to the local Tim Hortons’ drive-through before continuing on to Toronto.

At 8:30 a.m. we pulled into the church parking lot at 161 Skyway Avenue. From the outside the cathedral was a towering sandy-bricked castle. The prospect of attending church in a castle excited the children. Having brought my digital camera, I snapped some photos of the exterior before heading inside.

At 8:30 a.m. we pulled into the church parking lot at 161 Skyway Avenue. From the outside the cathedral was a towering sandy-bricked castle. The prospect of attending church in a castle excited the children. Having brought my digital camera, I snapped some photos of the exterior before heading inside.

The first thing to hit me upon entering the sanctuary was the predominance of the cross. The cross dominates the symbolism of the Assyrian cathedral’s worship space. There are crosses lying flat on waist-high podiums near each entrance; the faithful bow, kiss the cross and make the sign of the cross as they enter the sanctuary. There are a number of devotional candles in front of other crosses, where one would find icons among Byzantine Christians or statues among Latin Catholics. The faithful light these candles, make the sign of the cross, and pray. The cross also dominates the curtains separating the sanctuary from the nave. Later on during Qurbana, when the curtains were opened, I would stand awestruck by the huge stained-glass cross with backlighting that hung over the altar.

Bishop Emmanuel Yosip would later confirm this first impression over breakfast following the liturgy. Alone among ancient apostolic churches, he explained, the Assyrian Churches of the East for the most part lacks icons. (Though he added that the Eucharist is the one icon they possess). Thus the cross stands as their main symbol through which they interpret the liturgy, he said. It is always present with the Bible during the liturgy, with the cross representing Christ’s human body and the Bible representing His Spirit. The one exception during which the cross and Bible are briefly separated then brought back together, Bishop Emmanuel explained, is when the consecrated bread is fractured. This represents the separation of Christ’s body from His soul during His death on the cross.

Bishop Emmanuel Yosip would later confirm this first impression over breakfast following the liturgy. Alone among ancient apostolic churches, he explained, the Assyrian Churches of the East for the most part lacks icons. (Though he added that the Eucharist is the one icon they possess). Thus the cross stands as their main symbol through which they interpret the liturgy, he said. It is always present with the Bible during the liturgy, with the cross representing Christ’s human body and the Bible representing His Spirit. The one exception during which the cross and Bible are briefly separated then brought back together, Bishop Emmanuel explained, is when the consecrated bread is fractured. This represents the separation of Christ’s body from His soul during His death on the cross.

With regards to lack of iconography, Mar Emmanuel mentioned one theory – noting carefully that it was only a theory of contemporary Christian scholars and historians – that the Church of the East was forced to forgo icons not so much because of theological objections, but because of intense persecution suffered historically from the Islamic population. Thus the cross was deemed the most important symbol, in keeping with Holy Scripture and the teachings of St. Paul, through which to view Christ in the Gospel and in the liturgy. I had been familiar with this theory before arriving at the cathedral, and what I observed was consistent with it. Almost the entire liturgy commemorates Christ’s death, resurrection, ascension and the sending of the Holy Spirit. This is another interesting liturgical difference from Roman Catholicism, the bishop explained, where Christ’s death and resurrection are prominent in the weekly liturgy, but not the Ascension or Pentecost.

With regards to lack of iconography, Mar Emmanuel mentioned one theory – noting carefully that it was only a theory of contemporary Christian scholars and historians – that the Church of the East was forced to forgo icons not so much because of theological objections, but because of intense persecution suffered historically from the Islamic population. Thus the cross was deemed the most important symbol, in keeping with Holy Scripture and the teachings of St. Paul, through which to view Christ in the Gospel and in the liturgy. I had been familiar with this theory before arriving at the cathedral, and what I observed was consistent with it. Almost the entire liturgy commemorates Christ’s death, resurrection, ascension and the sending of the Holy Spirit. This is another interesting liturgical difference from Roman Catholicism, the bishop explained, where Christ’s death and resurrection are prominent in the weekly liturgy, but not the Ascension or Pentecost.

Back to my first experience praying the Holy Qurbana with the community. As Fr. Audisho had promised, Fr. Yousef met our family within the sanctuary. He introduced us to various deacons and laypeople within the community.

After introducing our family to various members of the congregation, Fr. Yousef helped us find a pew in the back of the sanctuary where I could snap photos without disrupting others at prayer throughout the liturgy. The worship service was sung from beginning to end in Aramaic and modern Assyrian, the entire community joining in to pray. The liturgy lasted approximately two hours. Fr. Yousef sat with us for the first hour, explaining various portions of the liturgy, its origins with Mar Addai and Mar Mari (of the 70 disciples sent out by Christ), pointing out some of the variants between its celebration in North America and the more traditional gestures in Iraq and what remains of the traditional Assyrian homeland. This was particularly noticeable during certain parts of the liturgy where younger members of the congregation sat and older members stood. Fr. Yousef also kept us on the right page in the missal.

The congregants were from all different generations. Though one could tell the majority were Middle-Eastern with regards to ethnicity. As the liturgy continued, more congregants—mainly mothers with children—filtered in. One thing that was noticeable throughout the congregation is that the women were veiled. What I found interesting is the Western Catholic origin of the mantillas worn. The most prominent design was that of Our Lady of Lourdes, which I recognized immediately but was hesitant to believe until seeing the word “Lourdes” written prominently under the silhouette of Our Lady of Lourdes printed into the veil. Other designs included crosses, Jesus pointing to his Sacred Heart, and either St. Michael or St. George putting down the serpent. I also noticed at least one lady with a Lourdes veil praying a western Catholic rosary. It appears as though the Assyrian Church of the East in Canada is not immune to Western Catholic influences.

The congregants were from all different generations. Though one could tell the majority were Middle-Eastern with regards to ethnicity. As the liturgy continued, more congregants—mainly mothers with children—filtered in. One thing that was noticeable throughout the congregation is that the women were veiled. What I found interesting is the Western Catholic origin of the mantillas worn. The most prominent design was that of Our Lady of Lourdes, which I recognized immediately but was hesitant to believe until seeing the word “Lourdes” written prominently under the silhouette of Our Lady of Lourdes printed into the veil. Other designs included crosses, Jesus pointing to his Sacred Heart, and either St. Michael or St. George putting down the serpent. I also noticed at least one lady with a Lourdes veil praying a western Catholic rosary. It appears as though the Assyrian Church of the East in Canada is not immune to Western Catholic influences.

Not too long after the Gospel reading, Fr. Yousef had to go vest before heading to the front of the sanctuary to assist Bishop Emmanuel with communion. Before leaving us, however, he asked a senior lay leader of the cathedral to remain with us and help us with any questions we might have about the liturgy. One thing I noticed about the liturgy is that the words of institution are said throughout the entire liturgy, rather than during a dedicated moment.

SHARING A COMMUNAL MEAL

What I had failed to realize over the phone is that the invitation to meet with the bishop after Qurbana was an invitation for my family and me to join the entire cathedral community for brunch in their dining hall. The bishop invited me to sit next to him at the head table. My wife and children sat at a nearby table reserved for them, next to the wife and children of a deacon assigned to help my family identify the various traditional breakfast dishes and also answer questions they may have about the community.

Mar Emmanuel was a very gracious host, giving me approximately 90 minutes of his time to answer a broad range of questions. We discussed our theological and ministerial background, after which he answered questions about history and theology of the Assyrian Church of the East. What struck me most was the hospitality and communal nature of the breakfast. One of the first things the bishop explained to me after the exchange of introductory pleasantries was that the communal breakfast following Sunday morning liturgy is very much a part of the Assyrian Christian tradition. These breakfasts allow him to remain connected to the people God has called him to pastor.

Throughout breakfast our conversation was interrupted frequently. Sometimes by children seeking a cookie or other treat from the bishop’s plate, sometimes by young couples and older members of the community seeking the bishop’s blessing. The bishop granted each of these requests with a warm smile and grandfatherly demeanor. While modern technology brings some advantages, the Bishop shared with me, we must be careful as a Christian community not to disconnect from human interaction because of it. Thus a communal meal is important because it allows those under his pastoral care to come together as a community, and it allows him to connect face-to-face with the people he pastors. The Bishop explained that communal meals were often the way in which Christ connected with His apostles, His disciples and the crowds who followed Him.

Throughout breakfast our conversation was interrupted frequently. Sometimes by children seeking a cookie or other treat from the bishop’s plate, sometimes by young couples and older members of the community seeking the bishop’s blessing. The bishop granted each of these requests with a warm smile and grandfatherly demeanor. While modern technology brings some advantages, the Bishop shared with me, we must be careful as a Christian community not to disconnect from human interaction because of it. Thus a communal meal is important because it allows those under his pastoral care to come together as a community, and it allows him to connect face-to-face with the people he pastors. The Bishop explained that communal meals were often the way in which Christ connected with His apostles, His disciples and the crowds who followed Him.

It was on a note of Christian hospitality that our visit ended. Knowing our family had come from out of town, and would be returning home today, the community prepared a picnic basket for us to take on the road. It included various Assyrian cheeses, breads, salad and a barbecue chicken. It included juice boxes and bottled water. Though unexpected, this hospitality was very much appreciated by the family and me. Over a month later my wife and children still reflect fondly upon our experience visiting the Assyrian Church of the East in Toronto for Sunday Qurbana, and the great hospitality extended toward us from the community.

FROM STUDENT ESSAY TO ECUMENICAL ENCOUNTER

It became obvious after speaking with my course professor that I would have to return for a followup visit in order to gather additional information for my assignment. Especially since the parish had no webpage, no bulletin, no regular weekly programming or even email address from which to garner additional information or correspond with the community.

A friend who is a local theologian happened to be running a course at the time on ministry within a multi-faith environment. His students were clergy, theologians, and pastoral workers. He invited me to speak to his students about my first encounter, and asked if he and those interested could tag along for the second. These students represented a broad range of Western Christianity. I passed the request on to Fr Audisho who gracefully invited us all down.

Because of conflicting schedules, pastoral emergencies within our local churches, and Bishop Emmanuel’s schedule, the first Sunday in December was the earliest that a followup visit could be scheduled. Especially since the pastors among us would have to schedule replacements to lead Sunday morning worship within their own churches.

My only reservation was with regards to the visit’s nature: I was following up in my capacity as a student from the Sheptytsky institute, not as a local ecumenical leader. I needed to finish the necessary research for my essay. My friend reassured me that he and his students would remain in the background, simply following my lead as Eastern Catholic aspiring to become an East-West ecumenist. When I explained to Fr. Audisho that I had set these limitations upon my colleagues, he laughed and told me not to worry. Toronto’s Assyrian Christian community would be honoured to receive us all, he said, and answer everyone’s questions.

Seven Western colleagues joined me for the followup visit. In terms of religious background, there were three Baptists, three Roman Catholics, an Anglican and myself as the sole Eastern Catholic. Other than the Anglican, none of the Protestants had previously attended a worship service of any Eastern Christian tradition. The Anglican and three Roman Catholics had only ever experienced Byzantine worship among the Eastern Christian traditions. None of my colleagues knew what to expect.

During my presentation that had led to my friend and his students tagging alone, I had shown two video clips from the documentary film The Last Assyrians. One key point I stressed during the presentation is that although the Assyrian Church of the East consider Nestorius a saint within their tradition, the term “Nestorian” is itself a pejorative when used by outsiders to their community. Members of the community might use it during our visit in a self-referential manner, but we as non-Assyrians should avoid using the term.

During my presentation that had led to my friend and his students tagging alone, I had shown two video clips from the documentary film The Last Assyrians. One key point I stressed during the presentation is that although the Assyrian Church of the East consider Nestorius a saint within their tradition, the term “Nestorian” is itself a pejorative when used by outsiders to their community. Members of the community might use it during our visit in a self-referential manner, but we as non-Assyrians should avoid using the term.

I illustrated this last point with an example from my initial visit to the community, when Bishop Emmanuel said to me: “One of the difficulties we encountered throughout our history is from Western missionaries coming to convert Nestorians to Western Christianity rather than convert non-Christians to Christianity.” I also attempted to explain, as best I could, the difference between “persons” and “Qnuma” within Assyrian Christology. During the hour-and-half trip to Toronto the following Sunday, I continued answering questions from my colleagues about Eastern Christianity in general and the Assyrian Church of the East in particular.

AN ECUMENICAL ENGAGEMENT

We arrived at the cathedral at around 8:45 a.m. The second visit followed the same basic format as the first. Fr. Yousef greeted us in the sanctuary and handed us all copies of the order of service. There was a dedicated pew for us at the back. Fr. Yousef introduced us to the community before Qurbana and shared a little bit about the cathedral and the liturgy. Fr. Audisho was present to assist the bishop, so Fr. Yousef stayed with us throughout the entire liturgy, offering similar explanations as he had to my family, and telling us which page to turn to in the missal whenever someone was lost. Parishioners I had met during my first visit welcomed us, asking me whether my wife and children had also come.

We arrived at the cathedral at around 8:45 a.m. The second visit followed the same basic format as the first. Fr. Yousef greeted us in the sanctuary and handed us all copies of the order of service. There was a dedicated pew for us at the back. Fr. Yousef introduced us to the community before Qurbana and shared a little bit about the cathedral and the liturgy. Fr. Audisho was present to assist the bishop, so Fr. Yousef stayed with us throughout the entire liturgy, offering similar explanations as he had to my family, and telling us which page to turn to in the missal whenever someone was lost. Parishioners I had met during my first visit welcomed us, asking me whether my wife and children had also come.

Nevertheless, there was one key differences in how we were received during this visit compared to my first visit. Bishop Emmanuel formally welcomed our delegation from the pulpit on behalf of the local Assyrian community.

DINNER AND DIALOGUE

After the liturgy, as members of the community left the sanctuary for the dining hall next door, Mar Emmanuel invited our delegation to pose for pictures with him. A visiting Bulgarian Orthodox priest from Mississauga, also in attendance, joined us for the photos. The bishop then invited our delegation to lunch with him and Fr. Audisho in a private room. The setting was much more intimate and allowed for a more open and candid dialogue after the introductory pleasantries. However, I also knew that in accepting this invitation I would have to forgo the opportunity to interview other members of the community and finish the research for my essay.

I was torn. My head told me I really needed to finish this essay, and that I would be putting my grade at risk. My heart told me to go with the moment, that in an ecumenical and multi-faith setting where the Eastern Christian minority are often misunderstood by our Western counterparts, this was the moment for which I had worked and prayed for years. Plus, would it really be prudent to refuse the Bishop’s invitation and insist upon imposing my own agenda? Thus I went with my heart and the opportunity to introduce some of my younger colleagues to Assyrian Christianity. (My professor, while grading my essay, later reassured me that I had made the right decision.)

Bishop Emmanuel sat at the head of the table, with Fr. Audisho to his right. I was invited to sit next to the bishop, but yielded my place to my friend the professor as he was both the senior scholar among us and the senior representative of the clergy and lay theologians present. Thus he is best placed to raise awareness of Eastern Christianity among local clergy and theologians. I sat next to my friend and across from Fr. Audisho, and the students filled in the remaining chairs, along with two senior lay members of the community who served our breakfast.

The first 45 minutes followed much the same format as my first visit. Bishop Emmanuel asked each of my colleagues to introduce themselves and share a little about their theological and ministerial background. He in turn introduced himself, and provided a quick overview of both the Assyrian Church of the East worldwide and the local Assyrian community. He fielded basic questions from my colleagues about the service and the community, their symbols in worship and Christology. Occasionally the Bishop consulted in the Assyrian language with Fr. Audisho when a question was not clear to him, and allowing Fr. Audisho to answer on his behalf when the bishop found it difficult to express himself in English.

One question from my Anglican colleague concerned the “removal” of the Filioque during their recitation of the Nicene Creed. Here the Bishop, Fr. Audisho and I presented a common Eastern front, explaining that the East had not removed the Filioque; rather the West had added it. Yet this question provided an excellent segue into the next 45 minutes of the conversation, where the Bishop provided candid answers to more delicate questions.

For our Anglican colleague, many of the questions were liturgical, including the absence of a clear moment during the Assyrian liturgy when the words of institution are recited over the bread and wine. Christology was another topic of interest raised by our Anglican colleague.

Our Baptist colleagues, in contrast, were less interested in Christology and the minutiae of liturgical divergence than in the topic of community. All three noted the communal nature of the liturgy, its dialogical style, and how the entire community sung the responses throughout the entire liturgy. All three felt that this was something lacking in the North American Baptist tradition, something that had been lost during the Protestant Reformation. The three Baptist ministers were also impressed by the Assyrian community gathering each week after service to share a common meal together. This led to a side conversation between Bishop Emmanuel and our Korean Baptist colleague on the challenges of maintaining the culture and customs among second and third generation immigrants among the worshipping community.

All of my colleagues were interested in hearing the bishop’s perspective on the current persecution of Christians in the Middle East. Here the bishop expressed his admiration and gratitude to Pope Francis for having recently come out publicly in the media in defence of Christian minorities in the area. Bishop Emmanuel then referred to the Diaspora in Canada and the United States as “bittersweet” – that is, he was happy they were able to find peace and freedom from persecution in Canada, but at the same time saddened that they were force to flee their homeland in Iraq. He noted that Islamists had driven out many of the minority Christian populations through kidnappings, bombings and murder. The lunch ended on a more optimistic note, as the bishop thanked us for coming, gave us his blessing, and gave us a carafe of Tim Horton’s coffee as a parting gift.

All of my colleagues were interested in hearing the bishop’s perspective on the current persecution of Christians in the Middle East. Here the bishop expressed his admiration and gratitude to Pope Francis for having recently come out publicly in the media in defence of Christian minorities in the area. Bishop Emmanuel then referred to the Diaspora in Canada and the United States as “bittersweet” – that is, he was happy they were able to find peace and freedom from persecution in Canada, but at the same time saddened that they were force to flee their homeland in Iraq. He noted that Islamists had driven out many of the minority Christian populations through kidnappings, bombings and murder. The lunch ended on a more optimistic note, as the bishop thanked us for coming, gave us his blessing, and gave us a carafe of Tim Horton’s coffee as a parting gift.

AFTER ACTION REFLECTIONS

The following Wednesday, my friend invited me to meet with him and his students in order to discuss our ecumenical encounter with Mar Emmanuel and the Assyrian Christian community. We had wanted to give the students a few days to reflect, but not too long as the course was ending the next day. During this time I carried out a group interview with all seven of my colleagues, in order to garner their reflections of this visit. I kept the questions simple: What had most impressed them about this visit? What had they learned about the Assyrian Church of the East and its local community? Would this experience in any way affect their ministry when engaged in ecumenical and multi-faith chaplaincy? And what had this visit taught them about their own Christian tradition?

Beginning with Des, a Haitian-born francophone Baptist minister who had immigrated to Canada as an adult, his reflection was simple: “This is a people who have suffered for the Gospel,” Des said. “And found strength in Christ and closeness in their community through their suffering.” That he focused on this aspect of the visit did not surprise me. Des has experienced similar suffering and impoverishment growing up and ministering in war-torn Haiti.

His English-speaking Baptist colleague Steve was most impressed by the communal worship style of the Assyrian liturgy. “Seeing the whole community come together, all different ages, and greet us and show us hospitality, was wonderful to witness,” Steve said. “And witnessing them worship together as a community, the chanting and the vestments. They are close-knit community that care for each other.” Steve was particularly drawn to how the community exchanges the sign of peace, folding their hands into each other in the prayer posture before raising them folded to one’s lips.

His English-speaking Baptist colleague Steve was most impressed by the communal worship style of the Assyrian liturgy. “Seeing the whole community come together, all different ages, and greet us and show us hospitality, was wonderful to witness,” Steve said. “And witnessing them worship together as a community, the chanting and the vestments. They are close-knit community that care for each other.” Steve was particularly drawn to how the community exchanges the sign of peace, folding their hands into each other in the prayer posture before raising them folded to one’s lips.

Jim, the aforementioned Korean Baptist minister, was also drawn to the inter-generational communal worship. “The whole congregation is part of the worship team,” he said. “Sometimes we do this as Baptists but not to this extent.” Jim was also drawn to the suffering and persecution faced by the Assyrian Christian community. “We must pay attention to their suffering. We must assist them and listen to their story. We must give them attention.”

John is an Anglican minister who had flown in from out-of-town to attend my friend’s course. “As a student of liturgy, the first thing that struck me was the relative austerity of the architecture. But when the people started chanting and playing their role, I realizes the worship space was just that—that space where the people provided the worship.” John was also drawn to the common elements between Anglican worship and Assyrian worship, although he noted they were often presented differently. “I felt very at home during their worship, despite not understanding the language it was being conducted in.”

Among the Catholics, Domi is a lay Roman Catholic with extensive experience in hospital chaplaincy. “The first thing that struck me was the warm welcome of the community. We were strangers to the community, not only at the religious level but the cultural one. Their warm hospitality was just as important as the service. That was at the level of the community. At the level of the Bishop, we were welcomed warmly to his table.” Domi was also struck by the liturgy. “Growing up as a Roman Catholic in Quebec, I was confronted by this liturgy much older than that of my own tradition. It forces me to reflect upon and appreciate the importance of tradition in worshiping God.”

Among the Catholics, Domi is a lay Roman Catholic with extensive experience in hospital chaplaincy. “The first thing that struck me was the warm welcome of the community. We were strangers to the community, not only at the religious level but the cultural one. Their warm hospitality was just as important as the service. That was at the level of the community. At the level of the Bishop, we were welcomed warmly to his table.” Domi was also struck by the liturgy. “Growing up as a Roman Catholic in Quebec, I was confronted by this liturgy much older than that of my own tradition. It forces me to reflect upon and appreciate the importance of tradition in worshiping God.”

Frank is also a Roman Catholic with extensive experience as an ecumenist. “I was stunned by the suffering they has experienced as Christians. Coming from Iraq they have experienced war, they have experienced persecution as Christians, and come through it with their faith.” Frank also spoke of the important of ecumenism and charitable dialogue among Christians. “We have to begin with a posture of listening, of recognizing each other as Christians and being charitable in our listening,” he said. “We may not always agree with each other, but we can be charitable in trying to understand each other.”

Finally, my friend Martin repeated many of the same points as his students, both liturgical and in terms of the hospitality extended. “I found the bishop was very open to answering our questions,” he said. Martin has since visited other Eastern Christian communities to expand both his knowledge and his social network among Eastern Christians.

CONCLUSION?

In the end, although I never finished my research for the class essay, I feel I learned the lessons that the professor hoped to impart through this encounter. That is, I met my Christian brothers and sisters within the Assyrian Church of the East, I worshipped with them, and was I was invited to share at their table. Moreover, I was allowed to share this experience of communal prayer and hospitality with those closest to me—namely, my wife and children, as well as my colleagues within the local ministerial and ecumenical community. For many of my colleagues, this was their first experience of Eastern Christianity. For all, it was their first (and my second) experience with the Assyrian Church of the East.

Nevertheless, this experience has yet to conclude. Now that I have met my Assyrian brothers and sisters in Christ, it is important that I continue to get to know them and learn about the Assyrian-Chaldean Christian Tradition. Since that time I have also visited Toronto’s Chaldean Catholic parish, experiencing their Qurbana as well. Members of both communities have told me that despite the current canonical separation, they remain quite close due to their their common history and the shared experience of suffering persecution for Christ’s name in the Middle East.