We’ve always been a people of the books (or the library), so it should come as no surprise that Modern Witchcraft has been shaped to some degree by the written word. Magickal people have always been captivated by books, even illiterate 17th and 18th Century cunningfolk were said to keep a few titles on their shelves just to impress their customers. But some books are more important than others, and I’d argue that the five played an outside role in the Witchcraft Revival of the 20th Century.

Before we begin, it’s important to point out that there are a lot of differing opinions on when Modern Witchcraft began (or if Witchcraft ever truly went away), but for the purposes of this article we are going to place the beginnings of the Modern Craft between 1935 and 1951. 1951 is when Gerald Gardner became the first, modern, public Witch (meaning he self-identified that way). He was allegedly initiated into a Witchcraft tradition in 1939, and since that implies that it predated him I’ve moved the goal posts back a few years. In addition, I think it’s likely that other people during that time frame were practicing something that would later be identified as Witchcraft.

THE GOLDEN BOUGH

BY SIR JAMES FRAZER Originally published in 1890, revised and expanded in 1900 and then again 1906-1915

It’s doubtful that most of us have read the entire Golden Bough (the third edition was 12 volumes long, and if you have read all of it congratulations!), but we’ve certainly all been influenced by it. Frazer’s greatest contribution to Modern Witchcraft was the “dying and resurrecting god” a theory generally discredited by scholars today, but one that still resonates with a lot of people.

Frazer’s central thesis in The Golden Bough was that all of the gods who died in antiquity were gods of vegetation and fertility, dying during the Earth’s barren periods and then returning with the year’s first new growth. Frazer believed that this was taken a step further in human cities, with (human and mortal) Divine Kings representing this vegetation god, with that king dying or being sacrificed to bring fertility back to the Earth. Much of Frazer’s motivation for writing The Golden Bough was due to his dislike of Christianity, as the book links Jesus to ancient pagan gods, with the implication that Jesus is just as silly as Dionysus, Osiris, and Baldur. (The idea of Jesus as a dying and resurrecting god and a shadow of other pagan deities is an idea has never quite gone away, and has spawned a cottage industry.)

Every time a group of Witch’s celebrates the sacrifice of The Horned God at Samhain (or Lammas or the Autumn Equinox) they are paying homage to the ideas of Frazer. While Frazer’s theory has not aged well, it’s very powerful poetically, and is easy enough to sync up with the Wheel of the Year and the eight sabbats of Witchcraft. Frazer was an atheist and would most likely have been horrified to find that his ideas were adopted to some degree by a bunch of Modern Pagans.

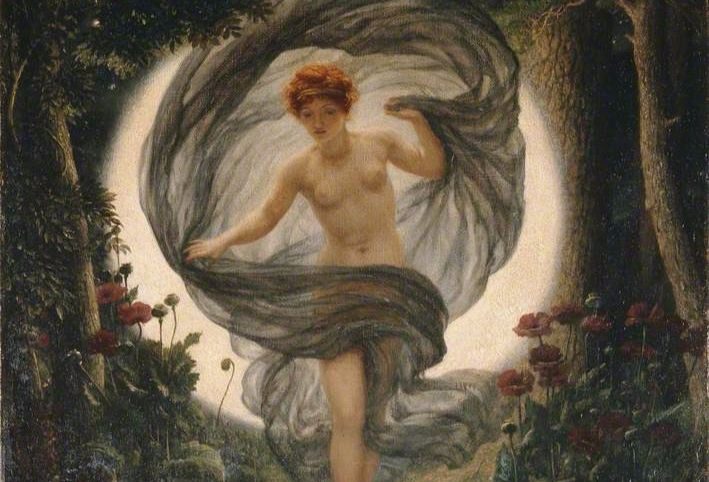

THE SEA PRIESTESS

by Dion Fortune Originally published in 1938

Dion Fortune didn’t invent the Goddess, but I think she went a long way in shaping how many Witches (and just Pagans in general) talk about her. I’ll be the first to admit that The Sea Priestess is far from a perfect book. It’s 300 pages long and only about 50 of those pages are really all that interesting, but OH THOSE 50 PAGES! When Fortune gets away from her silly protagonist and into the magical working of her tale things go from meh to great and much of the power in that working comes directly from how Fortune’s ritual unfolds and how the Goddess is described.

About twenty years before Doreen Valiente articulated the “Universal Goddess” prevalent in many types of Witchcraft today (“Listen to the words of the Great Mother, who was of old also called Artemis; Astarte; Diana; Melusine; Aphrodite; Cerridwen; Dana; Arianrhod; Isis; Bride; and by many other names . . .”), Fortune did so, and nearly as poetically. In the passage below she ties

“I am the soundless, boundless, bitter sea;

All things in the end shall come to me.

Mine is the kingdom of Persephone,

The inner earth, where lead the pathways three.

Who drinks the waters of that hidden well

Shall see the things whereof he dare not tell-

Shall tread the shadowy path that leads to me-

Diana of the Ways and Hecate,

Selene of the Moon, Persephone.”

Just peaking through The Sea Priestess for this article has reminded me of just how powerful and amazing her prose can be when writing about the Goddess. Summing up the Lady of the Moon Fortune writes:

“But likewise in the souls of men a flowing and an ebbing of the tides of life, which no one knoweth save the wise; and over these tides the Great Goddess presides under her aspect of the Moon. She comes from the sea as the evening star, and the magnetic waters of earth rise in flood. She sinks as Persephone in the western ocean and the waters flow back into the inner earth and become still in the grate lake of darkness wherein are the moon and stars reflected. Whoso is still as the dark underworld lake of Persephone sees the tides of the Unseen moving therein, and knoweth all things. Therefore is Luna called the giver of visions.”

When staring my Wiccan journey in the early 90’s such passages would have felt right at home in the multitude of Llewellyn books I was consuming at the time.

Fortune’s influence goes further than just verbalizing the idea of an all-encompassing universal Goddess, the main working written about in The Sea Priestess reads like an early version of the ceremony known as drawing down the moon. The book’s secondary protagonist, the comically named Le Fey Morgan, calls the Goddess into her in the book’s most inspiring chapter, and does so while expressing the idea of gender polarity-an idea that was commonplace in early Witchcraft.

“Out of my hands he takes his destiny

Touch of my hands confers polarity

These are the moon tides, these belong to me-

Hera in heaven, on Earth, Persephone;

Levanah of the tides, and Hecate.

Diana of the Moon, Star of the Sea,

Isis Unveiled, and Ea, Binah, Ge!”

I’ve written before about The Sea Priestess, but the more I study the mysteries of the Craft, the more I see the influence of Dion Fortune.

THE WHITE GODDESS

by Robert Graves Originally published in 1948

The White Goddess is one of those seminal Pagan building blocks that I find nearly impossible to read. Though it sort of reads as history, it’s secondary title shines a little more light on its actual contents: “a Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth.” It’s those last words that truly sum up The White Goddess, it’s not so much a journey through history, but a journey through a new mythology, one that’s practically poetic when boiled down to its component parts. When asked about the writing of The White Goddess Graves always expressed the idea that his pen was being pushed by a higher power, and not some sort of academic quest for absolute historical truth.

Hidden in the pages of The White Goddess is an idea central to many forms of Witchcraft: The Triple Goddess, the Goddess as Maiden, Mother, and Crone. Even Witches and Pagans who have never heard of Graves or his book are familiar with his greatest mythological creation, and he did create a new myth. In the Ancient World there were Maiden goddesses, and Mother goddesses, and Crone goddesses (and Warrior goddesses and lots of other goddess), but they were never really three in one. When a Goddess was expressed in triplicate (or more) it was generally to show off her many attributes, not that she had three phases of life as a prt of herself that made up whole.

But Graves’ idea just makes so much sense that it’s hard not to adopt, and find beauty in. When I celebrate the Wheel of the Year and see The Goddess as going through stages on a yearly journey I’m using the ideas of Graves. They are just too good of a fit not to use, and have been in use in Witchcraft since at least the 1960’s. (The rituals of Robert Cochrane were hugely influenced by The White Goddess.)

If Maiden, Mother, and Crone in One weren’t enough, Graves also took the influence of Frazer one step further in the creation of the Oak King/Holly King myth. In ancient mythology there are warriors who battle, but not warriors who magically survive death, disappear for six months, and then reclaim their thrones in an annual cycle. Bits of the myth appear in various places (parts of The Mabinogian come to mind) but it’s not the entire story most of know today, it’s bits and pieces, and Graves put them together to create a new myth. There are some writers who think Graves is the most important and influential Witch and Pagan writer of them all, and while I disagree, I do acknowledge that he was highly influential.

This article is ridiculously long, to help loading times on your mobile device it’s continued at the link below.