In August of 2017 The Atlantic’s website published an article entitled Why Are There No New Major Religions? It’s a fun article, and name-checks a few contemporary religious and spiritual movements, most noticeably Scientology (which is sort of a cousin) and the veneration of Santa Muerte, a deity/folk-saint popular in both Catholic and magickal circles. What the article does not mention is Wicca, and while I’m not surprised, I will admit to being disappointed.

While Wicca has managed to work its way into the public consciousness over the last thirty years especially, it’s most often presented as little more than a curiosity. The more benign articles promise Witchcraft like you’ve never seen it before (though go Hudson Valley!) while the articles written by assholes simply mock it. If Google News is any indicator most media outlets don’t think much about it at all.

Wicca’s lack of public profile is especially surprising when considering how many Wiccans there might be in the United States. The American Religious Identification Survey is the most quoted survey of religious adherents and in 2008 it estimated that there were about 600,000 Neo-Pagans in the United States, with somewhere near half of them identifying as Wiccan. A far more generous estimate as to the number of Wiccans can be found at the website Religious Tolerance which estimates that as of 2015 there might be three million Wiccans in the USA. If that number is anywhere close to accurate it would make Wicca the country’s third largest religious tradition, about half the size of Judaism and double that of Islam*. (Atheists and Agnostics rank second and third behind Christians, but the latter two aren’t really religions are they?) Even if there are just two million Contemporary Pagans in the United States, that would mean there’s probably a million people who identify as Wiccan. That’s still a very strong number,

The idea that Wicca is the third largest religious practice in the United States is a bit mind-blowing, so take a second to let it sink in. Pretty cool huh? But despite our numbers no one seems to really be paying much attention to us. In 2016 the Trump campaign courted Amish voters, and there are only 250,000 Amish living in the US! At the very least we are one of the four largest religious traditions in the United States, and with the exception of Gary Johnson in 2012 no one to my knowledge has ever courted our votes (and Johnson didn’t even court Wiccans specifically).

If there is somewhere between one and three millions Wiccans in the United States, why are we so often ignored by the rest of America? I think the answer lies in a few key places . . . . . .

Wicca Has No Founder

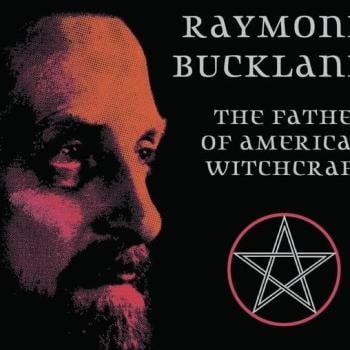

Gerald Gardner was the first person to publicly identify with a practice that today we might refer to today as Wicca, but I’m not sure that makes him Wicca’s “founder.” (For the record though, Wicca was not a word Gardner used, he was a Witch first and foremost, with “The Wica” being a subset of that.) Gardner was and is an immensely important figure, but he himself talked about being initiated by other Witches, and acknowledged that there were other Witch covens beyond that of his initiators.

This is in marked contrast to founders of other modern day religions who claimed to have a direct pipeline to a higher power and/or knowledge. L. Ron Hubbard’s works are still seen as holy writ in Scientology while Mormonism’s Joseph Smith is known as “The Prophet.” No one calls Gerald Gardner the Prophet and his books, while useful, are not the be all and end all of Wicca. Even the very specific Wiccan tradition that contains Old Gerald’s name (Gardnerian Witchcraft) has been shaped by others. I don’t think most people in the media know how to deal with a religious tradition that lacks a messianic figure.

No Centralized Authority

Most religions don’t have one centralized authority, but the largest ones have denominations with millions (and sometimes billions) of adherents. The Pope doesn’t speak for all Christians, but he does speak for about a billion Catholics. A little closer to home the Southern Baptist Convention has 15 million members, and while no one group speaks for all Evangelical Christians the SBC at least offers some insight into that religious grouping. Who speaks for the Wiccans? Nobody really. I can’t imagine a group of 100 Wiccans agreeing on a spokesperson, let alone a million.

The media likes easy answers, and there are no easy answers within Wicca. Covens are mostly autonomous (something that goes back to Gardner), and most Wiccans lack the institutional structures that come with some sort of centralized authority. Groups of Muslims, Hindus, and Buddhists build mosques and temples in the United States, but Wiccans generally don’t build Witch cottages or standing stones. There’s more than enough of us to do such things, but there’s power in not having a centralized authority and being able to practice in one’s home. The ease in which an individual can set up a Wiccan practice is one of the faith’s strengths.

Having a Wiccan-Popess would probably help with visibility, but Wiccans aren’t sheep, we don’t need that kind of garbage.

It’s Nebulous

My wife has been Wiccan for her entire adult life, but we are both rather sure that she’s still on the rolls of the Catholic Church. Because we don’t have any sort of centralized authority no one is going around adding Wiccans to church rolls, or keeping them there after they’ve left the tradition. Christian churches have a vested financial interest in letting non-active members remain on their rolls, Wiccans not so much.

Since most people don’t grow up Wiccan (though that’s slowly changing, but I’m sure it remains far from the norm) it’s a very easy religion to fall in and out of. One can be a Wiccan for a couple of years, and because there are no family or societal pressures to stay there, they can easily go back to doing what they did before or go on to do nothing spiritual at all. When one grows up Catholic or Jewish that stuff stays with you, and because it’s such an ingrained part of family life it’s sometimes impossible to leave completely behind. (My wife and I still celebrate Christmas for example and Easter feels like a holiday even though we have no real attachment to it today.)

Think of it this way: Susie grows up Catholic, discovers Wicca in college and practices for several years. The Catholic Church never removes her from its rolls, and she still goes to mass on Christmas Eve with her parents just to be a good daughter. After ten years of quietly practicing Wicca she gets married and goes back to the Catholic Church. During those ten years she was probably labeled as a Catholic by society (and the Church) and since there is no Wiccan Church there’s no Wiccan group to ever say “she was one of us.” Wicca is a faith that’s easy to drift in and out of, which makes it harder to count our numbers and gain any traction in our greater society.

Orthodoxy Vs. Orthopraxy

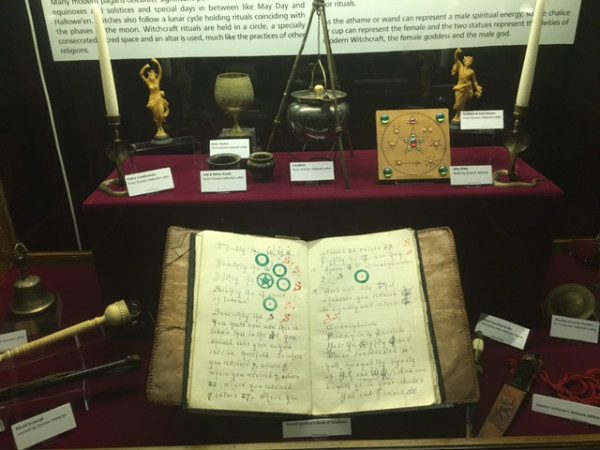

Most religions are about what you believe, and within Wicca that’s not really the case. There are a few generalities most of us see: celebration of the sabbats, (at least) lip-service to a Goddess and most likely a God, a belief in magick, but even within these categories there’s a lot of variation. Belief in a Goddess and/or God is not an absolute requirement within Wicca, and there are atheist, polytheist, and just about every other kind of religious-theist within Modern Wicca.

Wicca is probably best defined by its ritual practice, but even then there’s a lot of variation. Some call this orthopraxy, but that term is really a bit of a stretch. Orthopraxy is “correct practice” and there’s no one correct practice of Wicca. There are a lot of things most of us share when it comes to practice: tools, quarter calls, circles, the sabbats, etc., but there’s no one correct way to do those things. Maybe we are orthopraxy-light?

No One Knows Exactly When It Started

The media loves a good origin story (or a nefarious one) and Wicca lacks such a thing. There’s no one divine light from on top of a mountain or a voice whispering in the wilderness when it comes to Wicca. There’s also no “one moment” that can be pointed to as the start of Wicca. I usually use 1939, the year Gardner was allegedly initiated into a Witch-coven, but then again, if he was initiated, it was into something that predated him. In 1951 Gardner went public with being a Witch, which is another good starting point, but it’s not all that interesting (besides I think he was initiated into something).

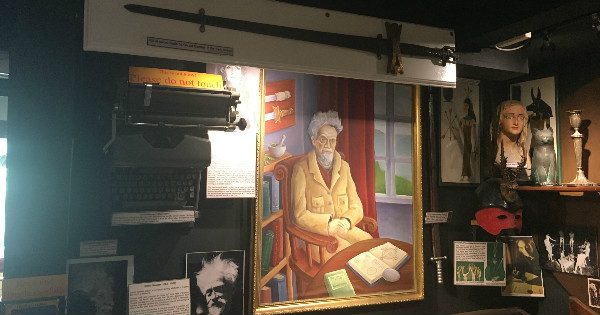

Wicca has also changed a great deal since the days of Gardner and his possible initiators. I’d argue that it’s no longer an initiation-only tradition, and perhaps that change-over marks the true start of Modern Wicca? (That would be the early 1970’s with the publication of the first “how to” Witch books, things like Lady Sheba’s Book of Shadows or Paul Huson’s Mastering Witchcraft.) Our narrative isn’t as cool as being born in a manger, and lacks a central defining moment like so many other major world religions.

People Have Trouble Taking Magick Seriously

The Modern World is extremely uncomfortable with magick, and even less sure how to react to people who practice it regularly. Natural allies like atheists often mock us for our belief in magick, as does the liberal media. (Making fun of Modern Witches seems to be something even “tolerant” folks feel comfortable getting away with.) The sad thing is that magick has always been a part of our society, and people often practice it today without realizing that they are doing so. What’s knocking on wood or throwing salt over one’s shoulder if not a magickal act?

I’d never advocate removing the magickal equation from Wicca in some ill-advised attempt at being seen as more legitimate. Magick is a part of our bread and butter (and cakes and ale) and helps define who we are. The media rarely mocks religious pilgrimage or praying the rosary, why can’t magick just be accepted as something we do? We certainly aren’t asking everyone to believe in or practice it.

So there you go, we are a major religion. Hopefully the rest of the country will one day get over their prejudices and start treating us as such.

*An earlier edit of this article stated that Wicca could be the second largest religious tradition in the United States, and that would be true if one uses an estimate of two million when it comes to adherents of Judaism. Most surveys place that number far higher though, at about five to seven million people, or 2% of the population (with the lower number being more common in most surveys).

I’ll admit I was taken in by a survey suggesting two million Jews in the United States, and that most definitely feels off to me. However, Judaism is both a religion and an expression of cultural identity. For instance 23% of Jews in the United States don’t believe in a higher power, in that case are they still practicing Judaism? And one could most certainly be Jewish and practice Witchcraft, does one then take precedence over the other? Questions of religious identity are often difficult.