Several years ago I was lucky enough to present a massive Samhain ritual at a Masonic hall in Santa Cruz, California. Though rather nondescript on the outside, the building hosted a lodge room (the Masons’ name for a meeting space) that looked to me like a ballroom in a medieval castle. Even more impressive was how that room simmered with energy. It wasn’t witchy energy, but it was close, and that’s most likely because Modern Witchcraft has borrowed and adapted a whole host of things from the Masons.

A great deal of the terminology we use today comes straight from Freemasonry. Phrases such as “So mote it be” and “Merry meet, and merry part, and merry meet again” were used in Masonic lodges long before they were uttered in a magick circle. (1) Even “the Craft” as a synonym for Witchcraft and Wicca comes from the Masons.(2) Masonry has influenced more than Modern Witchcraft; it has influenced dozens of occult orders since the 1700s. If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then groups ranging from the Mormon Church to the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn owe the Masons a large debt.

It’s not an exaggeration to suggest that Freemasonry has played a role in the initiation rituals of every occult and esoteric group of the last 350 years. Even groups that weren’t directly influenced by the Masons most likely picked up something from them secondhand. Masonry has been influential not just because of its longevity but also because its rituals (especially those pertaining to initiation and elevation) are effective.

To many people the Masons are an esoteric and occult order par excellence, and to others they are simply a harmless fraternal organization. The truth of the matter probably lies between the two extremes. Esoteric knowledge can be found in Freemasonry if one is looking for it, and if someone isn’t seeking such things, the order can be experienced without those elements. The level of mystery to be found in Masonry is up to each individual member. Much like Witchcraft, Masonry provides a place to experience many mysteries, but how those mysteries are interpreted and received will vary from person to person.

Much of the intrigue that’s attached to the Masons today comes from the rather speculative origins of the order. Depending on who one talks to, the Masons have either existed since biblical times or were formed a little more than 300 years ago when four Masonic groups in London got together in 1717 and formed a Grand Lodge. That first Grand Lodge then claimed authority over all the other Masonic groups in England. (3) While Freemasonry doesn’t date back to biblical times, it certainly predates the eighteenth century and most likely emerged during the medieval period, slowly transforming from a guild of Scottish stonemasons into a strictly fraternal order. (4)

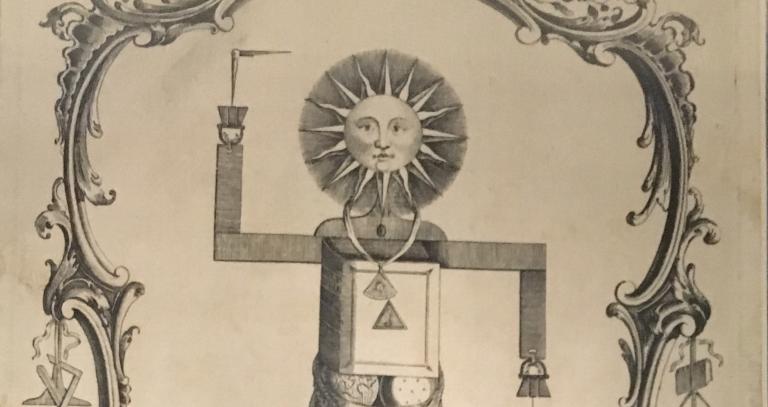

Evidence of Masonry’s roots in the medieval guilds can be seen in tools such as the square and the compass, which would have been used by stonemasons to build churches and castles. Further evidence comes from a series of texts known as the Old Charges, which date from 1380 and provide structure and guidance as to the behavior of stonemasons, along with instructions on how to run meetings. (5) Beginning around 1600, a new series of rules were applied to masonic guilds, regulating their structure and assembly, and this eventually lead to non-operative masons, the term applied to people who joined the guild but were not actual stonemasons. Once people outside the actual profession of masonry were allowed in, the medieval guild became a fraternal organization instead of a business group.

Skilled trade groups in the medieval period had a three-tiered system of advancement (apprentice, journeyman, master), and it seems likely that this system had some sort of influence on the Masonic degree system. Today, first-degree Masons are known as Entered Apprentices and third-degree Masons are called Master Masons. The exception is the second degree, which is known as Fellow Craft in Masonry. It stands to reason that apprentices, journeymen, and masters all might have had their own initiation and elevation rites, which were absorbed into Freemasonry when it transitioned from medieval guild to fraternal order.

Masonic initiation and elevation rites have become so influential over the last several centuries because they are designed to be transformative. Not only do they reveal knowledge generally reserved for Masons, (6) but they also offer previously hidden wisdom and often employ frightening and disorienting techniques that lead to an overly emotional state. As we move later in this chapter into the ideas and practices found in many Witchcraft rites pertaining to initiation and elevation, we’ll see many of the same techniques and concepts used by the Masons.

Written accounts of Masonic ritual include stories of being blind- folded, walking curious paths, and other uncomfortable moments. In his book Turning the Hiram Key, Robert Lomas states that during his initiation into Masonry he “had been blindfolded and walked around an unseen obstacle course…[and then] cramped into a distorted foetal position for another quarter of an hour.” (7) In Lomas’s account he mentions repeatedly how walking in what seemed to him at the time nonsensical paths while blindfolded created a heightened sense of vulnerability, emotion, and excitement, with all the sensory deprivation softening him up. (8)

In addition to blindfolding initiates and leading them around by a rope called a “cable tow,” the initiation and elevation rites also included physical threats. A swordsman oversaw the initiation rite’s beginning, and at one point a knife was held to the bare breast of the initiate. In the third-degree rite, the elevating Mason was thrown backward, only to land on a piece of taut canvas that kept him from hitting the floor. (This is according to Duncan’s Monitor; I’m sure something else is used in this day and age.) At the end of the initiation rite, the Masonic seeker was warned that “terrible and violent” retribution would come to anyone who shared the secrets of Freemasonry. (9) (No one can say with certainty whether such threats were ever carried out; it all depends on what history of the Masons one is reading.)

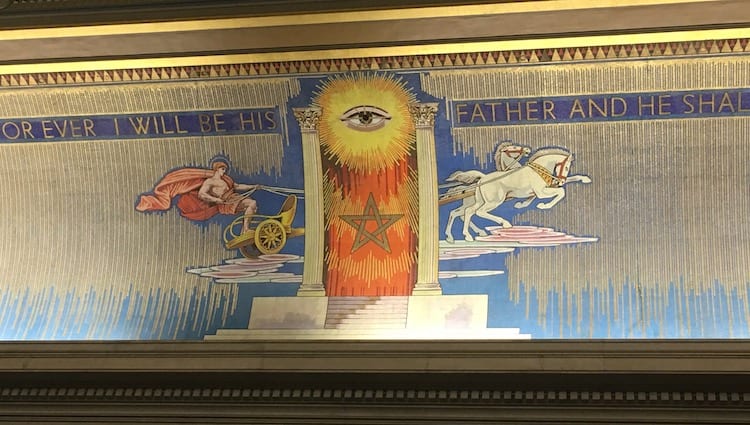

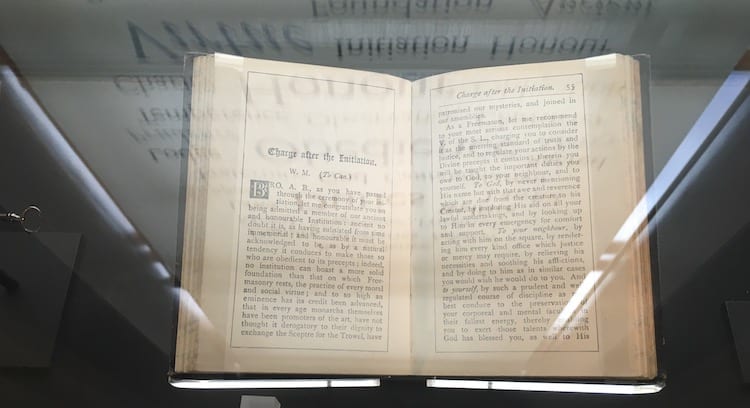

Along with the disorientation and physical threats, Masonic rites also reveal hidden truths. In the Entered Apprentice rite, the initiate is said to have begun his journey “long been in darkness, and now seeks to be brought to light.” (10) Later in the ritual, the seeker is brought up to the lodge’s main altar, where the blindfold is removed and the initiate is greeted by a loud “clap” by those attending the rite, along with a bright, blinding light (especially hard on the eyes after being blindfolded). (11) There the initiating Mason’s chosen holy book (referred to as the Volume of Sacred Law) is revealed, along with the compass and the square.(12)

The symbolism and truths of the Masonic third degree are even more startling. There the Mason seeking the degree of Master is again blindfolded and made to reenact the murder of Hiram, the alleged builder of Solomon’s Temple (the first temple of Jewish tradition). Over the course of the drama, the elevating Mason is pushed downward to enact their symbolic death before being raised up in an embrace called the “five points of fellowship”: foot to foot, knee to knee, breast to breast, hand to back, and cheek to cheek (mouth to ear). According to legend, Hiram’s body was somehow raised from the earth by an individual who touched his corpse at these five points. (That doesn’t seem like a very effective way to pick up a corpse, but at least it’s poetic.)

Following Hiram’s symbolic death and raising, the soon-to-be Master Mason is taught the final secrets of Masonry, including handshakes, passwords, and a Masonic word, which had to be recreated after Hiram’s death (the original having been lost). Because Masonic rites were meant to be kept secret, I’m uncomfortable writing about them too much in this book, but the major points outlined here were an inspiration for many Witches, though our rites have generally taken on a uniqueness of their own.

Excerpted and adapted from the book Transformative Witchcraft: The Greater Mysteries by Jason Mankey, Copyright 2019, Llewellyn Worldwide. More excerpts from Transformative Witchcraft can be found below:

The Eleusian Mysteries: Initiation in the Ancient World

NOTES

1. Nabarz, The Square and the Circle: The Influences of Freemasonry on Wicca and Paganism, 80–81.

2. Nabarz, The Square and the Circle, 70.

3. Ridley, The Freemasons: A History of the World’s Most Powerful Secret Society, 33. Despite its rather grandiose title, this is a rather sober book on Masonic history.

4. Bogdan, Western Esotericism and Rituals of Initiation, 69.

5. Bogdan, Western Esotericism and Rituals of Initiation, 68–69.

6. 108. Many of Masonry’s secrets have been hiding in plain sight for over a hundred years now. In 1866, Malcolm Duncan published what has come to be known as Duncan’s Masonic Ritual and Monitor, a guidebook of Masonic ritual. I don’t think modern Masonic ritual coincides completely with Duncan’s, but many of the ideas and practices are the same. All of my quotations of Masonic ritual are from this text.

7. Lomas, Turning the Hiram Key, 59–60. Lomas’s book goes into Masonic ritual in great detail and is for sale at the United Grand Lodge in London, so the order must not have much of a problem with it.

8. Lomas, Turning the Hiram Key, 45–49.

9. Stavish, Freemasonry, 53.

10. This is from the “Seventh Order of Business” section of the Entered Apprentice rite in Duncan’s Masonic Ritual and Monitor.

11. Lomas, Turning the Hiram Key, 48.

12. Stavish, Freemasonry, 52.