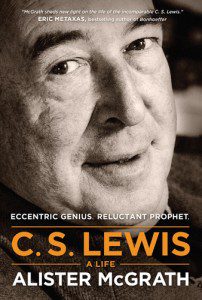

Full disclosure: I’m an unabashed C.S. Lewis fan – so I’m prone to gushing on the subject. Nevertheless, I think it’s not at all overstating to say that reading Alister McGrath’s new biography of C.S. Lewis is well worth your time. As far as biographies go, it’s not terribly long at 379 pages, and with such a colorful narrative, Lewis’s life is ready made for a biography such as this.

Full disclosure: I’m an unabashed C.S. Lewis fan – so I’m prone to gushing on the subject. Nevertheless, I think it’s not at all overstating to say that reading Alister McGrath’s new biography of C.S. Lewis is well worth your time. As far as biographies go, it’s not terribly long at 379 pages, and with such a colorful narrative, Lewis’s life is ready made for a biography such as this.

What makes McGrath’s telling of C.S. Lewis’s life stand out is that McGrath is not only a quality Christian historian, but also a world class theologian in his own right. His ability to portray the personal narrative and history alongside the development and assessment of content (Not only Lewis’s, but especially with regard to the other writings of the time – who was holding sway and why), gives this work considerable depth.

The well known movements of Lewis’s life are all here in full force. His mother died when he was only nine years old. His father had no emotional intelligence at all and promptly shipped Lewis off to boarding schools where he was terribly out of place and likely abused physically – if not sexually – and emotionally. He escaped to Oxford and owing to his sheer genius, and despite his awkward social ability and eccentricities, found his way to the top of the intellectual and social heap of England in the 1940s and 1950s. His atheism and later conversion to Christianity are told with great detail. Lewis’s relationship with Joy Gresham is particularly well treated. McGrath says that there is no doubt in his mind that she set out to seduce and marry Lewis before she had ever even met him. McGrath portrays Lewis as a somewhat reluctant apologist for Christianity, whose writings have stood the test of time, lasting into a post-modern culture with surprising force.

McGrath pulled a few details in that I had not remembered from other works on Lewis’s life. For instance, as a college student Lewis acquired a sort of fetish with bondage (sexual fantasy). He does great work on the odd relationship between Lewis and Mrs. Moore – the mother of an army buddy with whom Lewis seems to have had a sexual relationship despite the fact that she was much older. They lived together for decades and it was one of the most significant relationships of his life. Lewis’s role in the genesis of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings was also well done. It seems obvious that the world would have never known about middle earth were it not for Lewis’s friendship with Tolkien. McGrath’s take on Lewis’s lifelong friendship with Arthur Greeves was good. Greeves came out of the closet to Lewis (McGrath believes that Greeves hoped Lewis would come out as well – which he did not), but their unique friendship survived and remained one of the most important of his life. McGrath pulls no punches with brother Warnie’s alcoholism.

I believe that McGrath’s is the first major biography written since the publication of Lewis’s collected letters in 2006 – nearly 3500 pages of personal correspondence including cross-references. This means that McGrath’s biography is perhaps the most accurate portrayal of C.S. Lewis’s life to date.

My only disappointment with the book is also one of its greatest strengths – it is written in a fairly dispassionate mode. McGrath’s telling of the life of C.S. Lewis is rendered without a lot of heat. I often found myself thinking that McGrath was holding back a bit – as though he had more to say here, but it would have ventured into the realm of personal opinion and editorial commentary. He stayed away from that for the most part. Not to say that it is apathetic or cold – not in the least – but the book seldom makes a move toward judgment or commentary about Lewis’ personal narrative. McGrath is such an expert in these matters, I would have liked to hear more about what he thinks personally – especially at several key points. Most of McGrath’s passion is reserved for an assessment of Lewis’ writings, which was clearly the strongest point of this work and where McGrath’s biography is hands down the best I’ve read. His ability to place Lewis’s writings among their original context sheds new light on these old familiar texts.

McGrath’s big moment is that he is able to prove quite convincingly that nearly all other biographers of C.S. Lewis have the date of his conversion wrong. The reason for the mistake is that Lewis gave a date later in his life, but seems to have been confused. This is a pretty big adjustment in the world of Lewis-geeks. McGrath changed a significant date for Lewis studies. Here’s the quote.

“Lewis’s subjective location of the event in his inner world is accepted, but his chronological location of the event is seen to have been misplaced… Lewis’s location of this event in the external world of space and time appears to be inaccurate. Lewis’s conversion is best understood as having taken place in the Trinity Term of 1930, not 1929. In 1930, Trinity Term fell between 27 April and 21 June.” p. 14

The book is well worth the price and the time it takes to read it. I’m grateful to McGrath that he took on this enormous project and pushed through to what may well be the definitive work on Lewis’s life to date.