Editors’ Note: This article is part of the Patheos Public Square on Remembering the Dead: Ancestors, Rituals, Relics. Read other perspectives here.

A few years ago my friend Chris Jehle asked me to begin making a trek to the hood in KCMO to help him with a peculiar task. Chris had spent the previous fifteen years living in one of the most poverty entangled and violent neighborhoods in our nation. At the time he was the founder of The Hope Center, a magnificent ministry that pours life and hope into the lives of children and families who live at the core of our city. This neighborhood is an exceedingly violent place. Gunshots were common. Shooting deaths were the norm.

While working in this neighborhood, Chris developed a deep love for the Old Testament. In the Prophets he found the words he needed to express the plight of the city. In the Torah he found the basic instructions for what it means to be the people of God. That’s where he got the idea to drag me out of the suburbs to help him with the task of claiming bodies.

While the Israelites inhabited the Promised Land local towns were given a morbid task, one that Chris and I were attempting to emulate. If a traveller succumbed to death on the road, the nearest town was required to claim the body and bury it appropriately. It was their responsibility to bear witness to the reality of death, thereby showing that they held an appropriate value for life. No body should rot in the ditch without the people of God naming death as the enemy and claiming the body for the Lord.

When someone died in Chris’ neighborhood, as they often did—young men mostly—it was common for no memorial service to be held. A lack of money, family, or any sort of connection to faith or the church sometimes meant that the body would go unclaimed. The death would hang over the neighborhood like a so much unfinished business. The unlamented violence, the unsolved crime, the unclaimed body combined the fuel the spirit of death that just hung in the air. At some point it simply became too difficult for Chris to breathe. So he called on me to help him with an idea he had, a way to clear the spirits. Chris wanted to claim each unclaimed body for the church.

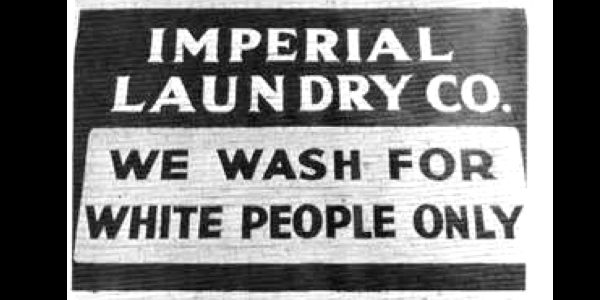

To his credit Chris was straight with me on why he wanted me there. For all of the coverage the urban core gets on the nightly news (if it bleeds it leads), the suburbs are still relatively insulated from the violence. Suburbanites can and do completely ignore the fact that young black men are dying in droves in a neighborhood beset with a nearly complete social breakdown that is at least partly, if not totally, by design. I was there to bear witness on behalf of the suburbs to a death that was bound up top to bottom in injustice. I was there to confess that our affluent suburban way of life made the violence and poverty of this neighborhood inevitable.

The first time we tried this, the death had occurred in a crack house only a few days before. The investigation was all but closed. The police were never going to find the young man’s killer. Our plan was to return to the scene of the crime and say a funeral liturgy. We sat in the front seat of my car across the street from the mostly boarded up house. Chris told me it wouldn’t be safe to get out and stand on the street to say the liturgy, so we stayed in the car.

It was surreal, like a covert funeral stakeout. Chris was nervous, which was not normal, and it unnerved me as well. We prayed with our eyes open, scanning the street in both directions—this was not a safe neighborhood by any stretch. Tensions were high on the block since the incident. An unfamiliar car at the scene of the crime, two white guys crossing themselves, sitting with their heads bowed in the front seat of a beat up Maxima… it would’ve been a bit strange.

The liturgy was one that I adapted from the Book of Common Prayer for the occasion. The file on my hard-drive is titled “A Liturgy For the Dead of Our City.” It’s the same one I now use when I’m called upon to say a funeral for one of the homeless men or women from my congregation, which happens as many as four or five times a year.

The prayers of the funeral liturgy are beautiful. It’s a shame that these words—so full of hope, poetic and rich with eschatological imagery—are only shared at funerals. I’ve begun looking for chances to draw them into other occasions. I use the old English version. The original language is lyrical.

Man that is born of a woman hath but a short time to live, and is full of misery. He cometh up, and is cut down, like a flower; he fleeth as it were a shadow, and never continueth in one stay. In the midst of life we are in death: of whom may we seek for succor, but of thee, O Lord, who for our sins art justly displeased? …

Forasmuch as it hath pleased Almighty God of his great mercy to take unto himself the soul of our dear brother here departed, we therefore commit his body to the ground; earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust; in sure and certain hope of the Resurrection to eternal life, through our Lord Jesus Christ; who shall change our vile body, that it may be like unto his glorious body, according to the mighty working, whereby he is able to subdue all things to himself. The Lord bless him and keep him, the Lord make his face to shine upon him and be gracious unto him, the Lord lift up his countenance upon him and give him peace. Amen.

Part of the service from the BCP involves a call and response.

Leader: Thou only are immortal, the creator and maker of mankind; and we are mortal, formed of the earth, and unto earth shall we return. For so thou didst ordain when thou created me, saying, “Dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.” All we go down to the dust; yet even at the grave we make our song; “Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia.”

All: Give rest, O Christ, to thy servant with thy saints, where sorrow and pain are no more, neither sighing, but life everlasting

Leader: In to thy hands, O merciful Savior, we commend thy servant N. Acknowledge, we humbly ask thee, a sheep of thine own fold, a lamb of thine own flock, a sinner of thine own redeeming. Receive him/her into the arms of thy mercy, into the blessed rest of everlasting peace, and into the glorious company of the saints in light.

All: Give rest, O Christ, to thy servant with thy saints, where sorrow and pain are no more, neither sighing, but life everlasting

Leader: Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death, and giving life to those in the tomb. The Sun of Righteousness is gloriously risen, giving light to those who sat in darkness and in the shadow of death. The Lord will guide our feet into the way of peace, having taken away the sin of the world. Christ will open the kingdom of heaven to all who believe in his Name, saying, “Come, O blessed of my Father; inherit the kingdom prepared for you.”

Chris had the call; I had the response. Over and over I said those words, “Give rest, O Christ… where sorrow and pain are no more.” It confirmed in me an already semi-hardened conviction: When it comes to the funeral liturgy, pastors should stick to the script. The script is beautiful. It really doesn’t need our help. It lacks nothing… nothing but a voice.

That’s the pastor’s job. You are simply the voice. You are not the author or redactor. At best you are an editor for style and context, not content. The words have the power to transcend; they only need your voice.

The first rule for pastors when it comes to funerals should be: don’t try to be cute. Give voice to the words that have been given to you, the words to which you have been given. These words have been in use for centuries. They are lacking in nothing except a voice. Receive them with reverence. Purify your hearts and speak them with probity. Adapt them sparingly to suit the occasion, and remember this: The people need to hear you say the words with a note of reverence in your voice. Give rest, O Christ, to thy servant with thy saints, where sorrow and pain are no more, neither sighing, but life everlasting.