Every year my church spends the month of November studying the lives of four different saints. Typically I only hear the name Walter Rauschenbusch when it precedes a misleading caricature of the Social Gospel movement. Here’s my attempt to commend this great saint to the church.

Every year my church spends the month of November studying the lives of four different saints. Typically I only hear the name Walter Rauschenbusch when it precedes a misleading caricature of the Social Gospel movement. Here’s my attempt to commend this great saint to the church.

In one of my favorite seminary courses we were assigned the book A Theology for the Social Gospel, by Walter Rauschenbusch. I had never heard of Rauschenbusch, so my plan was to hurry through it so I could get on to Karl Barth or Reinhold Niebuhr, guys I cared about. But, the book so captured my imagination that I read everything of Rauschenbusch I could get my hands on. I even wrote my first book, in part, as an attempt to reinterpret Rauschenbusch from a post-liberal point of view. [An Evangelical Social Gospel?]

Walter Rauschenbusch’s family came from Germany in the mid 1800s. Six generations of Rauschenbusch men before him had been pastors including his father August, who moved to America & converted to the Baptist Denomination (not exactly pleasing his German Lutheran family). Walter was the first Rauschenbusch to be born in America (1861), and he grew up in Rochester, NY. His father was a professor at the Baptist Seminary. His mother and father were living in what was, by all accounts, an extremely unhappy marriage. In fact, when Walter was four years old his mother took the kids to Germany without her husband, where they stayed for four years. They returned when Walter was eight years old, so that he could begin school.By that time he was already comfortable speaking & reading both German and English.

Walter was a really smart kid, creative & curious. At age sixteen he became quite serious about his faith in God, & from then on it was assumed he was headed for the ministry. When he finished high school, his father took him to Germany to The Gymnasium at Gutersloh. German prep schools were so rigorous that graduation was considered equivalent to a bachelor’s degree in America. Usually boys would enter at age nine, & graduate at age eighteen. Walter began at age fourteen, thus he was quite far behind at the outset.

Rauschenbusch, however, was an incredibly hard-worker, and he threw himself into his studies. By his senior year he was first in his class. He came home to go to Seminary, and once again graduated at the top of his class in 1886. When he did, he had his pick of ministry assignments. Larger English-speaking Baptist churches wanted him to pastor. Colleges wanted him on their faculty. Fresh out of seminary himeself, the Baptist seminary in India recruited him to be their new president.

Rauschenbusch surprised everyone when he turned them all down, and took a job as the pastor of a small German speaking congregation, Second Baptist Church, in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood of New York City. Today the neighborhood is the gentrified home to stars like Madonna and Seinfeld. Back then it was the worst slum in the city, the seedy underbelly of Manhattan ripe with prostitution, gambling, gangs, and violence. Rauschenbusch one said it had more saloons that churches. If you’ve ever seen Gangs of New York, it’s set in the same time, and an adjoining neighborhood.

Most of the German immigrants lived in Hell’s Kitchen, and worked in the garment industry turning their cramped apartments into small factories sewing and assembling dresses to take to the foreman who would find a nit-picky reason not to pay full price. Anyone who argued too much would be fire, since there were hundreds of people ready to take their job. Those who worked in factories had it worse. At the time, the U.S. had highest rate of industrial injuries in the world. On average, 35,000 people a year died at work, with little or no compensation and often no punishment when employers were at fault.

Most immigrants worked 60 hours a week for eight to ten dollars a week–not nearly enough to live on–but that was okay since there was a good possibility you would die before your disappointing paycheck came. To make ends meet families would often take on borders to share their tenement apartments. Often two full families (10-12 people) would cram into these dark, overpriced, 3-room apartments. Landlords were bound by no laws & took horrible advantage of renters. They could evict people for no reason at any time, without warning, so, of course the immigrants put up with the rats & mice & bugs & diseases that spread so quickly & killed so many… especially the children. Nearly 70% of all deaths in the tenements were children five years old and under.

Few people cared about the immigrants. They were cheap labor, that’s all, and their lives were expendable.

We’ve all heard of the famous first voyage of the Titanic that sank in 1912, killing 1500 people. A decade earlier the Steamship Slocum caught fire just off Manhattan while carrying 1500 German Lutherans heading to a church picnic. The lifeboats had been wired in place, and life preservers were rotted & useless. Over 1000 German immigrants died that day. Why have we never heard of that disaster? Because they were all poor, and they were all immigrants. The company who ran the vessel wasn’t even punished for their negligence.

That’s the world Walter Rauschenbusch faced. This wet-behind-the-ears seminary graduate waded into the deep end of the pool & became the pastor of Hell’s Kitchen’s Second Baptist Church, a job which meant a lot of things you might not normally associate with that role.

Rauschenbusch was more than just a preacher to his congregation. He was often asked to be an unofficial lawyer, or counselor, and interpreter, advisor & representative. When his parishioners needed help, they couldn’t call a lawyer because they didn’t have the money. They couldn’t call the police because they were corrupt. They only had two real options: call the gangs, or call the pastor. Walter did much more than just preside over weddings & funerals. He was intimately involved in the lives of his parishioners, bearing their burdens as he was interpreting for them, advising them, and helping them navigate a culture that was foreign to them.

This mean that, on a daily basis, this upper middle class whiz kid who had been given every advantage found himself face to face with grinding poverty and infuriating injustice. The problems his people faced broke his heart, made him mad, and eventually messed with his theology.

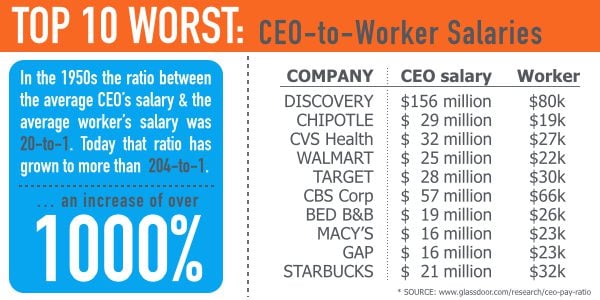

What made the poverty & injustice even more absurd was that, just a few blocks uptown, New York’s high society was living in lavish affluence. This was the era of the Robber Barons. There were no labor unions, safety regulations, or child labor laws, and there was a huge disparity between rich & poor. The rich were completely insulated from the lower class. They were living in the same city, but they were in two different worlds.

Rauschenbusch did all he could for his people, but the way society was organized, he found there wasn’t much he could do to change their situation.

He told story of a woman in his church whose husband was run over by a streetcar & killed. It was the streetcar driver’s fault, so the company offered her $100 compensation for her loss. The amount would barely cover the cost of a funeral. Rauschenbusch went to the company on the woman’s behalf & asked for more money. They told him that $5K was the legal limit, but the streetcars killed so many people in Manhattan everyday that they’d go bankrupt if they paid that much to each family. If they wanted more money, they’d have to sue to get it. The woman lacked the money for a lawsuit, and it wouldn’t have mattered anyway, because the company had plenty of judges on the payroll. In the end, gave her a hundred dollars in $1 bills to make it look like more money.

Rauschenbusch wasn’t used to bearing these injustices, but now faced them everyday. He saw how those who ran the systems didn’t care about those on the bottom, and he felt he had to do something—he just didn’t know what. So, he began by writing for newspapers, and telling people’s stories.

He told one story about a tailor whose daughter was dying of consumption (T.B.). For months the man had worked all day, then hurried home to spend all night rocking his dying daughter. Already exhausted & heartbroken, he knew that she was only getting worse. He left for work that morning knowing his daughter would die that day, but he couldn’t stay with her because his boss promised to fire him if he didn’t come in to work.

Rauschenbusch wrote this in a newspaper article, and he told his readers that the next time they found themselves annoyed with the man who was altering their suit because he didn’t speak perfect English, or wasn’t working fast enough to suit them, maybe they should check & see if he’s choking back tears because his little girl was about to die, and he was stuck at work fitting rich people with new suits of clothes.

Rauschenbusch wrote scores of articles like this, & they had an impact. He was kind of an anomaly—at home with the immigrants in the tenements, speaking German & living in squalor—but as part of the clerical class, he was also educated, well traveled, and comfortable rubbing shoulders with society’s elite. He & his wife maintained a close friendship with Aura & John D. Rockefeller for years. As Rauschenbusch navigated these two worlds he realized that the gospel he preached was of little use in either situation. Typically, both the poor and the rich considered themselves to be Christians.

When he preached a gospel of personal salvation to the poor, he felt as if he was saying, “I know your life is miserable right now, but everything will be ok when you finally die.” It seemed cruel, and did nothing to offer them hope for today.

When he preached personal salvation to the rich, felt like saying, “Your callousness & indifference to the poor people living just down the street doesn’t matter. You’re ticket’s punched for heaven, so you’re good.” It seemed careless, and did nothing to call them to account for how they treated the vulnberable.

A theological crisis occurred in his mind. If the gospel was good news at all, it had to be good news to the woman who’s husband was killed by the streetcar, & the man whose boss wouldn’t let him stay with his dying daughter. It had to call the rich to do more for the poor. So Rauschenbusch dug into the scriptures, and for years he immersed himself in the lives of the people and the teachings of Jesus in the bible.

He noticed that the gospel of personal conversion was not something Jesus seemed overly concerned with. Look for yourself. Jesus hardly ever talked about it personal salvation. There was, however, nearly always a social dimension to the teachings of Jesus. He meant for the gospel to change the situation for those who were suffering and living on the margins of culture.

When John the Baptist was in prison and he realized he was probably going to die, he sent his followers to as Jesus to see if Jesus was really the Messiah. It’s like he was saying, “I’m about to die for you… tell me you know what you are doing.”

Jesus’s answer was anything but straight forward. “Go tell John what you hear and see: that the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news [euangellion] brought to them.”

John’s question was, “Are you the Messiah.” Are you the king of Israel? Are you the one to bring the KOG to earth?

Jesus’ answer was: if the blind receive sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor receive good news, then you know God’s kingdom is coming.

Rauschenbusch began to see that for Jesus, the Gospel and the coming of the kingdom of God (God reigning in all the earth) were one and the same. He noticed the word Kingdom or kingdom of God appeared 162 in the New Testament, usually on the lips of Jesus himself. He noticed John the Baptist preached about the kingdom. Jesus preached about the kingdom. The Apostle Paul preached about the kingdom. Jesus told his followers to preach about the kingdom.

The lights went on for Rauschenbusch, and he saw the words “thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven” contained much more power than just how to get into heaven when you die. He wrote, “Christ’s conception of the kingdom of God came to me as a new revelation. Here was the idea and purpose that had dominated the mind of the Master himself. All his teachings center about it. His life was given to it. His death was suffered for it. When a man has once seen that in the Gospels, he can never unsee it again.”

So when we read a text like our story for today from John 13, with an eye toward Jesus’s teaching about the kingdom, we see things we didn’t used to see:

“Jesus knew the Father had put him in complete charge of everything, that he came from God and was on his way back to God.” The beginning of this famous scene is a kingdom claim. Jesus is claiming that he’s in complete charge of everything. Who’s in charge of everything? Only a king. Once you see that you can’t unsee it.

“He got up from the supper table, set aside his robe, and put on an apron. Then he poured water into a basin and began to wash the feet of the disciples, drying them with his apron. When he got to Simon Peter, Peter said, “Master, you wash my feet?” Jesus answered, “You don’t understand now what I’m doing, but it will be clear enough to you later.” Peter persisted, “You’re not going to wash my feet, ever!” Jesus said, “If I don’t wash you, you can’t be part of what I’m doing.”

Jesus has just claimed kingship, yet he’s doing the job of the servant. This is fascinating to me. Jesus’s kingship is best expressed through servant hood. The washing of feet was a symbolic cleansing. Jesus told Peter—this is where it all starts. You have to let me do for you what you can’t do for yourself.

“After he had finished washing their feet, he took his robe, put it back on, and went back to his place at the table. You address me as ‘Teacher’ and ‘Master,’ and rightly so. That is what I am. So if I, the Master and Teacher, washed your feet, you must now wash each other’s feet. I’ve laid down a pattern for you. What I’ve done, you do. If you understand what I’m telling you, act like it. And you’ll find peace.”

Jesus changes back into the clothes of the teacher & he says: here’s your lesson; just as I washed your feet, so you wash each other’s feet. I’ve laid down the pattern for you & the pattern is servanthood. If you do this, you’ll find peace.

Here he doesn’t mean inner peace. He means shalom: the right ordering of your life, not just personally, but socially & relationally. Your common life will be rightly ordered when you serve one another.

The gospel of the KOG is not just about your personal salvation, although it’s certainly about that. It’s about human communities, & the way we organize our common life together. Jesus wants to redeem the systems of the world: economic, social, political, judicial, governmental, educational, and so on. He wants it all. Rauschenbusch discovered what the great Dutch church & political leader Abraham Kuyper had said:

“There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry, Mine!”

Jesus looks at everything that is & says, “Mine. I want all of it. I want to bring all of it back into right relationship to God.”

Walter Rauschenbusch rediscovered this & he began to preach it powerfully. First, Jesus comes to us and washes us clean. Then we go to each other & we serve one another unselfishly. And all of this is gospel. All of this is the good news of kingdom of God. As we allow the way we organize our common life together to come under the Lordship of Jesus, the kingdom of God, we will begin to experience God’s shalom, God’s peace, God’s ordering of creation.

Rauschenbusch kept right on talking about the aspect of the gospel that is personal—the redemption from sin, being washed clean thru Christ. But, he also began talking about the aspect of the gospel that is social. The gospel is personal in that it’s about your relationship with Jesus and the transformation of your life. The gospel is also social in that it’s about how relate to one another, and how God has chosen to bring all of creation back under the Lordship of Jesus. Rauschenbusch believed that anytime we untether those two things, we lose the power of the gospel, because Jesus is always at the nexus of those 2 things.

The example I use in the book I wrote on Rauschenbusch, is how rocket engines function in space. Space is a vacuum. Since here’s no oxygen, even the highly combustible rocket fuel they take with them won’t burn. If you want your rockets to fire in space, you have to carry your own oxygen. The power to get home is in the nexus of the two things, the mixture of rocket fuel and oxygen. The Gospel is like that. There’s a personal dimension between you & God, and there’s a social dimension between all of humanity and God, and between the systems of the world and the Lord who wants to redeem them. The power of the gospel is in holding those two together. If you lose one or the other, you lose the power because that’s where Jesus is. Rauschenbusch wrote,

“Whoever uncouples the religious and the social life has not understood Jesus. Whoever sets any bounds for the reconstructive power of the religious life over the social relations and institutions of men, to that extent denies the faith of the Master.”

We can’t separate our private faith, from our public life. They have to stay connected, or the gospel loses its power. Our faith cannot simply be private, because the kingdom of God is about all of life.

Whereas before he would talk about personal sin. Now he talked about the realities of social sins as well. He called people out for the way they treated the poor. He was fearless. From labor unions to political parties, government agencies to corporations, Rauschenbusch confronted anyone who selfishly served their own interests. He called them to serve the common good, and told them: There is no turning to God without a turning toward each other; there is no turning toward each other without turning first to God.

Whereas before he talked about the person in relation to God. Now he talked about social groups in relation to God as well. He drew heavily upon the prophets of Israel, and the way the prophets often described Israel as single entity who sinned together, suffered together & repented together. One of the ideas he popularized was that social entities are much more powerful than individuals. Groups impact society much more than persons.

Social groups have a more widespread influence than any one person. A Social groups lifespan outstretches a single person’s life. Social groups don’t cease to exist if a few members die, or leave, making them more impervious to criticism than individuals. (You want to leave our group? Fine. We’ve got so many members we’ll keep right on trucking.) Social groups have tremendous power to change behaviors. They can actually make good people do bad things. We see this in things like the Rwandan Genocide, where individuals who wouldn’t think of killing another person did so when asked by a group. Rauschenbusch thought that when social entities go bad it’s actually much worse than when a person goes bad because groups have a bigger and longer lasting impact.

Whereas before Rauschenbusch talked only about person salvation, now he talked about corporate salvation as well. By this he meant that it was possible for whole groups, corporations, even political parties and social organization to come under the Lordship of Jesus. He thought this to be a good thing, because social groups also have the power to make bad people do good things. People who might never be generous or share, will actually take part in virtuous behaviors because the group calls it out of them.

I see this all the time here at Redemption. On our own, none of us are really that holy, but we’re part of this church that calls something better out of us. I’m not that good on my own; but because of the goodness of the group, I’ll do much more good than I would when left to my own choices.

As Rauschenbusch preached about the gospel of the kingdom, it took fire among Christians in the U.S. The church began to work for the common good. As churches became more involved in communities and public life, things begin to change. Many things that we take for granted today began in this movement

- Public funding of education

- Public libraries

- Public museums

- Public parks & playgrounds

- Parcel Post

- Public transportation

- Public Telegraph/Phones

- Municipal Housing Programs

- Child labor laws

- Organized Labor

- Regulation of monopolies

- Inheritance Tax

- Workplace Safety Regulations

- Social Security:

Those things grew out of this movement called the Social Gospel. They made a big difference for quite awhile, & they still do in many ways.

One of the ways that Rauschenbusch stood out among other voices in the Social Gospel movement, was his insistence that this was not the work of human hands. This is the work of Christ in the world, in and through his people. Human hands were not generating these actions. Human hands were participating in God’s mission of redemption. He always knew there was a limit to what human hands could do.

Part of why I think Rauschenbusch always kept the idea of limits in mind is that throughout his time in New York, he was slowly going deaf. He had a degenerative condition, and was slowly losing his hearing. He knew there were limits to human ability to effect change. He lived with those limits everyday as he lost his hearing.

Eventually his hearing, along with the demands of his public life drove him to move back to Rochester, and join the faculty of the Seminary, where he taught and wrote and maintained a rigorous schedule promoting his ideas. Here are a few great segments of his writing.

“The individualistic gospel has taught us to see the sinfulness of every human heart and has inspired us with faith in the willingness and power of God to save every soul that comes to him. But it has not given us an adequate understanding of the sinfulness of the social order and its share in the sins of all individuals within it. It has not evoked faith in the will and power of God to redeem the permanent institutions of human society from their inherited guilt of oppression and extortion. Both our sense of sin and our faith in salvation have fallen short of the realities under its teaching. The social gospel seeks to bring men under repentance for their collective sins and to create a more sensitive and more modern conscience. It calls on us for the faith of the old prophets who believed in the salvation of nations. ”

“The purpose of all that Jesus said and did and hoped to do was always the social redemption of the entire life of the human race on earth. If we regard him in any sense as our leader and master, we cannot treat as secondary what to him was the essence of his mission. If we regard him as the Son of God, the revelation of the very mind and will and nature of the Eternal, the obligation to complete what he began comes upon us with an absolute claim to obedience… But the Jesus with whom his enemies dealt, and from whom they backed away, was never very passive. He was high-power energy from first to last. His death itself was action. It was the most terrific blow that organized evil ever got. He always moved with a purpose and his purpose always was the Kingdom of God. At the beginning he really hoped to win his nation. When he saw isolation and death impending, he accepted the law of vicarious suffering as part of the method of redemption, and took Death by the hand as God’s minister to bring the Kingdom. His death was his greatest act of social service. His cross was the climax of the world evil and the turning point of history toward a definite and permanent emancipation and redemption of the race. All the great permanent forces of evil in humanity were strangely combined in the drama of his death: bigotry, priestcraft, despotism, political corruption, militarism, and the mob spirit. They converged on him and did him to death. But he is alive, and now it is their turn.”