In my earlier post, I asked, “How does a modern, educated, middle-class child become an ideologically-motivated potential killer?”

If you were to put together a mental image of someone vulnerable to radicalization, what would that look like? Young, isolated, lonely? Mentally ill? Uneducated, under-employed?

We have ideas and expectations about who is–and therefore, who ISN’T–at risk for falling down the rabbit-hole of extremism and violence, but are these impressions accurate?

Fortunately, I’m far from the first or only person to ask that question.

A study looking at over 100 individuals indicted for ISIS-related activities in the US concluded that potential terrorists are not always very different from the rest of us:

As a group, the individuals mirror average Americans more than people think. The common perception of a terrorist as a young, single, unemployed, disenfranchised male is wrong: The average age of the 112 individuals is 27 years old, with almost a third over 30; more than 40 percent were in a relationship, with a third being married; while nearly two-thirds had been to college.

Three-quarters had jobs or were in school—figures similar to the U.S. population as a whole.

The vast majority of the 112 individuals are U.S. citizens. Nearly two-thirds were born in the United States, and nearly 20 percent were naturalized citizens. […]

A significant proportion includes converts from outside established Muslim communities. About 30 percent of the individuals are converts to Islam, including 43 percent of U.S.-born indictees.

So maybe we aren’t looking at maladjusted underemployed loners? But what about non-ISIS extremists? And what about less obvious traits, like mental illness or amorality?

A different set of researchers looked at ideas, themes, and beliefs common among different groups of extremists.

Saucier and his colleagues…examined the published materials of 13 militant extremist groups, which they defined as groups that combine fanatical beliefs and values and advocacy of extremist means, including violence.

The extremists came from across regions, religions and cultures. They ranged from the Baader-Meinhof Gang (Germany) to Meir Kahane and followers (Palestine and Israel) to the Lord’s Resistance Army (Uganda) to the Tamil Tigers (Sri Lanka) to Aum Shinrikyo (Japan) to the Shining Path(Peru) to home-grown U.S. extremists like the Unabomber and Timothy McVeigh.

The researchers then extracted 16 key themes that occurred over and over in the texts.

When they asked British and Serbian college students to rank their agreement with the ideas and attitudes identified, they had mixed results. Positively, Serbian undergraduates were not more likely to endorse these extremist base beliefs than were British students, despite that country’s tumultuous history. On the other hand,

In survey after survey, students generally failed to strongly dissociate themselves from the sentiments.

“If, in fact, extremist thinking is something bizarre, you’d expect people to disagree with the statements,” said Gerard Saucier, a professor of psychology at the University of Oregon and the lead researcher on the study. “What you get instead is that they’re failing to disavow them. A typical showing is a mixture of agree and disagree.”

What are these attitudes and ideas that underlie so many extremist groups despite different religious, cultural, and ideological self-identification? What does Timothy McVeigh have in common with Baader-Meinhof and the Tamil Tigers?

What is it that Alexandre Bissonnette and Damien Clairmont very likely had in common, even though they came to identify with opposing religious and cultural identities?

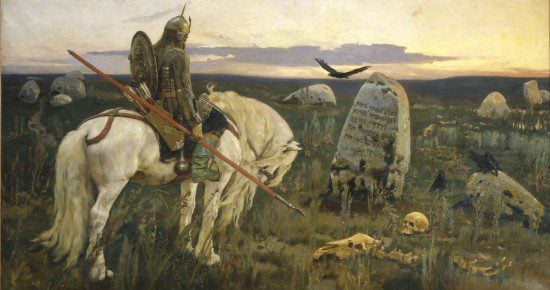

Taken together, the themes cohere into what Saucier and colleagues describe as a “seductive narrative”: The modern world has fallen into a catastrophic state. The ordinary mechanisms of change are no longer valid. Only extreme, violent measures can save things. This is a war of us against them, a war of good versus evil, a war of necessity. Any and all means are not only justified, they are glorified. God is on our side. In the end utopia will be restored.

These sound like extreme beliefs, don’t they? But Saucier found that while ordinary students were reluctant to endorse all of these, they were just as reluctant to disavow them. This initial openness may leave many people vulnerable to growing extremism under the influence of online and offline peer groups, mainstreaming of extreme positions and rhetoric, increasing ideological division, and social and political confusion.

If there is one thing the stories of Bissonnette, Clairmont, and so many others have in common, it is perhaps that they are too much like the rest of us–broken, lost, and searching for something to believe in.

As anthropologist Scott Atran says,

[T]he popular notion of a “clash of civilizations” between Islam and the West is woefully misleading. Violent extremism represents not the resurgence of traditional cultures, but their collapse, as young people unmoored from millennial traditions flail about in search of a social identity that gives personal significance and glory.

Bissonnette was tormented by bullies as a youth and became increasingly detached from the communities around him. Clairmont fell into adolescent depression that only lifted when he adopted the new belief system and fight that gave his comfortable adolescent life a larger purpose.

These are not unusual stories. What is unusual is not the lives these young men lived, but that their cries for identity and relevance were heard by extreme groups, answered,…and weaponized.