In a famous exchange, Dan Rather asked Mother Teresa of Calcutta what she says in prayer and she replied, “I don’t say anything. I listen.” Rather asked, “Well, then when you pray, what does God say?” She said, “He doesn’t say anything either. He listens.”

I often describe meditation in this way: Imagine you and a loved one on the couch, each sitting quietly, not talking, just being in each other’s presence. Not thinking, simply loving. You don’t need to talk.

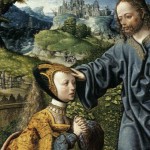

Meditation in the Christian tradition is sitting in the presence of God — not expecting answers, just being. And like sitting with a loved one, this simple act is heartening and strengthening.

Many people see meditation simply as quiet time — a refuge from their hectic lives. They know they’re spinning out of control a bit and they want some relief or some help. It is relief and it will help, but that’s not really what meditation is about. My meditation for Christians resource page here focuses on how to do it, so I want to expand on why it’s so useful. In particular, I want to speak to why it’s so useful for Christians, because there’s a lot of fear-based misinformation out there. I see it in comment threads; I hear it from churchgoers and friends. And most of the criticism starts with basic misunderstandings that meditation is “Eastern” and self-centered.

Anyone who makes even a cursory survey of the literature on the Christian contemplative practice of Centering Prayer will discover that its purpose is to cultivate one’s communion with God. While other forms of sitting meditation may not be as direct in this focus on God’s presence, almost all serve to help you become more awake and aware, and more accepting of reality just as it is, which in Christian terminology means accepting God’s Will as it unfolds, rather than fighting against it.

Obediently accepting

In meditation, we bask in the Love of God, but we also practice and deepen our experience of obedience and nonattachment. The Kenosis hymn found in Philippians 2 — one of the most ancient Christian hymns, chanted still by Catholic monks as part of their Vespers service — contains the best description of this obedience:

Though He was in the form of God,

Jesus did not deem equality with God

something to be grasped at.

Rather, he emptied himself,

and took the form of a slave,

being born in the likeness of men.

He was known to be of human estate,

and it was thus that he humbled himself,

obediently accepting even death

(part of the Kenosis hymn in Philippians 2:6-11;

version taken from The Liturgy of the Hours)

The translations in the Liturgy of the Hours, the NRSV and New American Bible use the term “slave,” but many say “servant.” Slave is better. To be human means to be a slave to reality, a slave to the laws of the material realm, including death. We must “obediently accept” our powerlessness in the face of this reality if we are to be at peace, with ourselves and with God. Even Jesus, as a human, was obedient to this truth.

The Original Sin of the Garden of Eden was that Adam and Eve grasped at equality with God. It is in trying to play God — trying to defy God’s Will and not accept reality the way it is — that we create suffering for others and ourselves. Jesus’ example, for us to model, is to not grasp at equality with God, but to obediently accept God’s Will and the laws of the physical realm, “even death.” This does not mean that the laws can’t be overruled — but rather that if this happens it is through grace, not through our applying our willpower to the situation.

“Of God Himself can no man think”

Perhaps the best explanation of why kenosis, or self-emptying, through meditation helps us to have this attitude modeled by Jesus — and thus why it is just as relevant for Christians as for anyone else — is in The Cloud of Unknowing, the 14th Century source on which Centering Prayer is based. While its Middle English is challenging, this mystical classic, written by a cloistered English monk, offers the patient reader rich guidance — the reasons to meditate, the pitfalls to watch out for, and techniques to aid in its effectiveness.

Here’s how it explains the reason for a Christian to practice silent meditation:

“For of all other creatures and their works, yea, and of the works of God’s self, may a man through grace have fullhead of knowing, and well he can think of them; but of God Himself can no man think. And therefore I would leave all that thing that I can think, and choose to my love that thing that I cannot think. For why: He may well be loved, but not thought. And therefore, although it be good sometimes to think of the kindness and the worthiness of God in special, and although it be a light and a part of contemplation: nevertheless yet in this work it shall be cast down and covered with a cloud of forgetting.”

In other words, you can know God only through loving God. Thinking about things of the world is fine; thinking about God can even “be a light and a part of contemplation,” but to fully open to loving God, you must set thinking aside and just be.