It’s fun to speculate about who will be the next pope. But normally there’s a bit of a taboo about that because you are talking about the current pope dying. Not this time. By resigning — the first pope to do so since 1415 — Pope Benedict is taking the naughtiness out of that game. He’s also giving the cardinals an opportunity to plan their trips to the Vatican by setting a date certain for his resignation.

None of this is a surprise, though the exact timing was not known. Pope Benedict spent years as Pope John Paul II’s closest advisor before and throughout the previous pontiff’s slow deterioration. He saw the harm that can be done by an incapacitated leader, and has said he would resign if and when he felt he could not fulfill his duties. It is a gift to the Church and a final unselfish act for this pope, who genuinely never wanted the job and can now look forward to at least some of the quiet retirement he had been looking forward to eight years ago.

Pope Benedict’s term has been a mixture of openings, as this theologian pope has tossed aside some backwards attitudes of the Church, and closings, as his traditionalist side has tried to shut the door on moves towards a more tolerant and progressive structure. Most on the left (for lack of a better term) gave him little hearing because he was already well-known to them as “God’s rottweiler” for his aggressiveness while working under Pope John Paul II in shutting down thinking and practices deemed unacceptable.

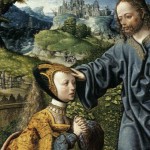

On the openings side of the ledger, Pope Benedict revived the idea that faith should be engaged with art. In both music and fine art, Benedict has encouraged dialogue, saying that by refusing to engage the modern world, the church was ceding it to secularists. The theologian in Pope Benedict couldn’t resist publicly denouncing the silly idea of limbo — never an official teaching but once widely accepted in the Church.

Most significantly, though, Pope Benedict confounded his enemies on the left by beginning his papacy with an encyclical titled “God is Love” and following it with other thoughtful letters, including one affirming unions and government social programs that totally freaked out conservative American Catholics, and two lovely gentle books about the life of Jesus.

The shift was in emphasis, though, not in beliefs. While as shepherd to billions, Benedict saw his main charge as being an inspirer and encourager of the faithful, he also took steps to bring back some traditional ways and to shut down debate on troublesome issues. Female priests? Forget it, closed issue, he said, which it is anything but, both among theologians and the public. Mass in Latin with the priest’s back to the congregation, which had never been banned at Vatican II, just kind of discouraged in the name of openness? Awesome. Openly gay priests, where some nuanced progress could have easily been made? No dice. And of course recently he went out of his way to denounce any idea of gay unions, ever, period.

He also presided over the ongoing scolding of American nuns for focusing too much on helping the poor and not enough on promoting the pro-life agenda, and on the denouncing of some liberal theological books and their authors — though some of the cause of these things falls on the American bishops, who are far to the right of their flock, and sometimes to the right of the pope, or at least more partisan then is he.

In sum, Pope Benedict followed a similar track in Catholic religious thought and politics as did the neoconservatives in American social thought and politics. Both were part of the liberalizing reform movements of the 60s — then-Bishop Ratzinger had been a key figure in Vatican II — and both felt that the movements overstepped, and in turning against them, retrenched into a traditionalism and hostility towards the aftermath that ended up painting them as enemies of the reform movements they had helped foster.

Despite being surrounded with friends, both Catholic and not, who have nothing good to say about Pope Benedict, and despite being on the other side from him on virtually every major question facing the Church today, I’ve never been able to hate him. Part of it is his quiet academic demeanor, which I relate to both personally and in authority figures I admire. Part of it is the central role one of his early Vatican II era books, Introduction to Christianity, played in my own faith journey. I still think of it often. I was baptized under him, and was in the 20th row when he visited New York. It’s also just not my style to be hostile toward people with whom I disagree. So let us say goodbye to the good and the bad aspects of Pope Benedict’s term, and look forward.

What next?

A new pope could take the first steps back towards the center. Except for one thing. A pope is elected by those cardinals who are under 80. Since between them Popes John Paul II and Benedict have served for 35 years, every single cardinal was appointed by them. So it’s very unlikely we’ll get a significantly more liberal pope. But just as with presidents’ appointments of Supreme Court justices, sometimes unexpected things can happen. Pope John Paul II surprised those who elected him by taking the church far to the right on social issues (which wouldn’t have been a surprise if they’d better understood Polish Catholicism). Similarly, the current cardinals might misread a candidate’s core.

But by definition the unexpected rarely happens. The next pope likely will be as conservative as the last two, though probably not with the focus on going backwards that Benedict has exhibited. There’s a strong possibility he will be African. British bookie Paddy Power currently has Cardinal Peter Turkson of Ghana and Nigerian Cardinal Francis Arinze at first and third. On the one hand, this would be a wonderful small-c catholic move, an acknowledgment of the increasing numbers and role of the African church. It would also make the third non-Italian pope in a row. On the other hand, the African church membership is much more socially conservative than Western members and neither of these candidates is likely to move the church away from its recent hard-line social stances. The other front runner, Cardinal Marc Ouellet of rural Quebec — who is a part of the same traditionally-leaning neo-con-like faction as Pope Benedict — is if anything more conservative. [NOTE: Paddy Power’s rankings have already changed, with Ouellet now leading and Arinze falling to 5th place with two Italians moving up ahead of him.]

Or course, Paddy Power had Cardinal Ratzinger in fourth place with 6 to 1 odds eight years ago before he was elected pope. (Its frontrunner then was Nigeria’s Arinze.)

The likelihood that the next pope will be as conservative as the last two and extend this current period another decade or two is particularly troubling for liberal Catholics, and for all who would like to see the church liberalize. Through several generations, they have waited to see the church make any significant gestures of moderation, to be met each time instead with moves even further to the right, with moves of reconciliation towards the more extreme right-wing factions and additional rebuffs of liberal thinkers and ideas.

Of course with any change of the guard can come the unexpected. We will soon see. More to come.