NOTE: The following is a guest post from my sainted father, Galen C. Dalrymple, director at iam2.org, an organization devoted to crowd-sourcing compassion and empowering ministries serving the neediest children in the world.

Recently the filmmakers of Not Today, along with my friends at Lovell-Fairchild, took my father to India to learn more about the film. He is an extraordinary man of God with a passion for these issues and stands at the helm of a faith-informed organization that can make a real difference for children in need of food, water or protection. His first and second reports on the trip are linked. Below is his third:

*

I went to India expecting to see poverty. It was, in fact, the reason we were going: to learn more about the plight of the Dalit peoples of India so we could tell others about them. I got what I came for. Our agenda included visiting several slums and schools for the slum children. The poverty I saw in India was not any more shocking than the poverty I saw in Haiti after the earthquake. The ugly face of poverty is not confined to one country or continent, but can be found anywhere one travels, if you aren’t afraid to go see it. Abject poverty is abject poverty, wherever it exists. And it’s heart-breaking.

This post will be about my personal reflections regarding our trip. Let me say up front that I’m not writing this to guilt anyone who is blessed to enjoy a comfortable lifestyle in a well-do-do country. That’s not my purpose. I merely want to share my thoughts and reactions to my sojourn in India.

I knew some about the Dalits before we travelled there, having heard about the “untouchables” for as long as I could remember. I knew that they were poor. I didn’t know how many there were (one estimate puts their population as 250 million) until I did some research. But research on the Internet and staring a person in the eye are two very different things.

In the slums of Hyderabad, Bangalore and Mumbai, wandering among the shacks and human detritus, seeing humans living in conditions that are far worse than most dogs in America experience, I kept coming back to this question: “Why was I born in the United States and why do I live in such wonderful conditions compared to these people?” In the sounds of the children, I could hear the long-distant echoes of my own little children at play, and I wondered why they’d been so fortunate to be born to an American family? How would I cope if I were living in such conditions? Would I even survive? What would my life expectancy be? What sorts of diseases would I have?

I had a horrible cold the entire time we were in India, and I knew that upon returning to the States I’d have my gall bladder removed. What would have happened to me in India if I lived in the slums all my life and had a gall bladder problem? Or a heart problem. Or if my son who lived in the slum with me developed cancer. Would there be any hope of treatment? How many must die in India simply because they have no access to decent medical care?

I found myself getting angry at those who keep the Dalits under foot. How can one person treat another person so crudely and then face himself in the mirror?

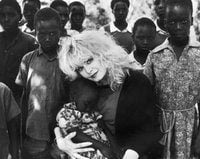

I am a photography enthusiast, and fortunate enough to own a very nice camera. I took it with me to chronicle our adventure. As we walked into the slums, I felt very self-conscious taking photographs. The people would stare at us as we walked between the “houses”. They weren’t hostile (with perhaps a few exceptions), but I felt uncomfortable just the same. How would I have felt if I were living in those conditions and a bunch of white people armed with cameras showed up in nice, air-conditioned vans, jumped out, started talking to us and began taking pictures of me and my children? Would I feel like an animal in a zoo, a circus freak, a cautionary tale, the prop for someone else’s passing spiritual experience?

I felt as if I were intruding into a sacred place…a place that I knew nothing about. And I was ashamed, as if we were making a spectacle of these people. Slum tourism. I knew we weren’t taking their pictures to exploit them, but to be able to communicate visually what we saw and experienced with the intention of encouraging other people to help these souls find a better way of life – and to stare deeply into our own comfortable lives for self-evaluation. Try as I might to be unintrusive, though, I felt that I was intruding with every step and click of the shutter. At times, the things I saw were so heart-breaking that I just couldn’t bring myself to press the shutter button.

But something else struck me just as powerfully. Nearly everywhere we went, even into the awful Mudfort Slum in Hyderabad, the people would smile at us and you could hear their cheerful chatter as they visited with one another and us, and see the luminous smiles on the children as they gamboled around us, begging us to take their pictures. Incredibly, beyond all belief, these people were happy. Or at the very least, content.

Why should they be content? Shouldn’t they want something better? Then it dawned on me: maybe they did want something better, but given the cultural realities of being a Dalit, they believed they could never have it, so they’d learned, as the apostle Paul had written so long ago, to be content no matter what their condition.

That’s when I began to realize that I am an American Dalit. Perhaps, in the aspects of life that truly matter the most, they were the rich ones and I am the poor one. I’ve grown so accustomed to being able to buy what I want when I want it, to live in a large, air-conditioned house in a quiet, safe, suburban neighborhood. I have access to health care even if it is expensive. I have access to clean water just by turning on a tap. We can go to the store and buy anything we want at any time. We lack for nothing…yet we seem to lack everything that really matters. And isn’t that perhaps the worst kind of poverty – not realizing how poor we are in spirit, in laughter, in love for God and family, not realizing how good we have it?

Why was I born in America? And what am I supposed to do about the plight of the Dalits, or the Haitians, or the Sudanese? I’m still wrestling with those questions. I don’t know the answers yet. But this I do know: I believe I, and all of us who are fortunate enough to live the privileged life we do live, need to do something. Something more than touring a slum and taking pictures.

Even a cursory read of the Bible makes it abundantly clear that God holds those who have much accountable for what they do with what they have. It’s bluntly stated that He deeply cares about the desperation of the poor, widows and orphans. He has made it clear that one day there will be a day of reckoning, and that such things will be taken into account (Matthew 25:31-46).

If the shoe was on the other foot and I were the one living in Mudfort Slum, I’d hope that someone, somewhere, would do something. Sometimes all people need is a hand to help start lifting them up – then they’ll be able to pull themselves up the rest of the way.

I hope they’ll be able to count on my outstretched hand. Can they count on yours?