In my time as a church musician, I have gotten more than an occasional gripe about why we have to sing all the stanzas of all the hymns. Often they come from the pews, occasionally they come from choir members. More often than you’d believe, they come from pastors.

Fortunately at my current post, this really isn’t an issue, but other places, it’s been made into a big deal.

Of course, there are many clergy who align a little closer with my perspective, like this fella who weighed in on Facebook recently:

“I’m a priest, and I agree that circumcising hymns for the sake of brevity is the same as circumcising Gentiles for the sake of the gospel. Paul was against the latter; I am against the former.”

So is it an unforgivable sin to occasionally, by which I really mean rarely, omit a stanza or two?

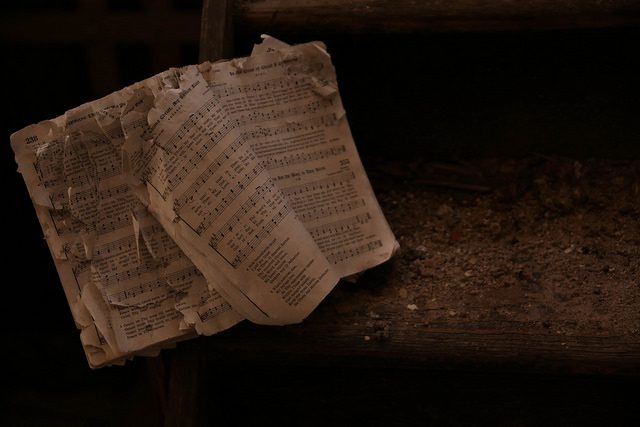

Probably not. Let’s be honest about this one. Most hymns in our hymnals have been altered in a myriad of ways from the original poetry. Archaic, exclusive language has sometimes been edited, theology has occasionally been tweaked, and more than these, stanzas have been removed. There are even very rare cases in which I always omit one of the stanzas that remain, like these:

- In Bill and Glo’s “Because He Lives” (which would take a pastoral decree for me to do in the first place), I always omit that silly second stanza about baby Benjy.

- In “Away In a Manger,” I always cut the second stanza because I refuse to believe that the little Lord Jesus never cried. Suggesting that he didn’t denies two thousand years of incarnational theology. Jesus the Christ was fully God and fully human. That means, like every other baby in history, he freaking had gas.

Again, let’s be honest. There is rarely, if ever, a really good reason to cut the hymn as it appears in a particular hymnal. Here are the two reasons I hear most often:

1. It’s boring to sing all the stanzas.

Maybe people will get bored if the hymn goes on longer than their attention span. So what? That’s their problem, not the hymn’s, not the organist’s, not the pastor’s. (Well, it kind of is the pastor’s problem when people start sending emails, but, whatever.) John Wesley said it quite well in his oft-quoted Directions for Singing:

Sing all. See that you join with the congregation as frequently as you can. Let not a slight degree of weakness or weariness hinder you. If it is a cross to you, take it up, and you will find it a blessing.

Pastors, when you get those emails, kindly respond like Johnny W. Music in worship, especially hymnody, is not a hook to keep people engaged, nor is it a tool to elicit good feelings, it is a discipline which must be developed. Just like the rest of the liturgy.

2. We need to save time.

No, you don’t. Not this way.

Again, speaking especially to pastors, the best way to save time during a worship service is to cut out announcements, which rarely do any good, anyway. Come on, you know this is true. If they weren’t already showing up to help mow the grass and trim the hedges, they’re still not coming after you bring it up in worship.

The next best way is to cut out small talk from the pulpit, which rarely does any good, anyway. In previous churches I’ve served, I have actually pulled recordings and timed the number of mid-liturgy explanations, impromptu personal anecdotes, and other self-indulgent blabberings. In churches that don’t adhere strictly to the liturgical script, the amount of time wasted on these diversions can be staggering.

After that, the best way to save time is to cut down sermons that last over 15 minutes, because those extra five, ten, fifteen, twenty, or however many minutes rarely do any good, anyway. Come on, pastors, you know this is true.

Honestly, all of these things, which have become commonplace in the contemporary church, do nothing but steal the liturgy from the people in the pews. A sermon is not supposed to be the focal point of Christian liturgy, but should be a concise exposition and expounding on the texts for the day given to the people as part of their work. So, give worship back to the people. Let them lift their own voices, and save your own for when it’s really needed.

Oh, and by the way, cutting stanzas from hymns doesn’t save much time, anyway.

Back at a previous position of mine, the one where “Norman the Baby Boomer Methodist Pastor” promoted “Crystal the Middle-Aged Trained Paralegal/Untrained Musician” to be my boss, this was a real point of contention. One of the first Sundays after her reign of terror began, Crystal confronted me on Facebook Messenger about my choosing to do all seven stanzas of the Methodist national anthem, also known as “O For a Thousand Tongues to Sing.”

It went something like this.

Crystal the MATPUM: The traditional worship experience went over again. Remember, you need to be off the stage by 10:40. Gotta cut some of the verses next time.

Jonathan: Oh really? That was a pretty short hymn, I thought.

Crystal: Seven is too many verses in general. Need to cut to four, or maybe even three.

Jonathan: I just timed it myself, and each stanza took under 15 seconds a piece.

Crystal: Well, the band was late getting on the stage

Jonathan: When you did announcements at the beginning, you spoke for nearly 8 minutes. I could see the clock in the back from the choir loft. Instead of trying to save mere seconds by chopping down a two-line hymn, could you possibly keep announcements to three minutes or so? It would save a lot of time and wouldn’t take anything away from the congregation.

Crystal: We’ve talked about this before, Jonathan. It’s important that I take an active role in your worship experience, and those announcements were decided upon by the staff, anyway.

Jonathan: I understand, Crystal, but I promise you it wasn’t too long. Maybe we should have a conversation with Pastor Norman about this.

Crystal: I’ve already talked with Norman. He was surprised you kept to the seven verses.

Jonathan: Well, he didn’t indicate to me that we should make any changes, so I just went ahead as planned.

Crystal: We’ve talked about this before too, Jonathan. If Norman goes over, it’s still your job to end on time.

Jonathan: Well, what about last week in the contemporary service when you…

Crystal: Yes, contemporary EXPERIENCE. What about it?

Jonathan: Sorry…er…experience, but what about when you sang “One Thing Remains” by Jesus Culture at the end and it went on for nearly eight minutes before you wrapped it up? You were only repeating the refrain, which is what? Ten words? You were repeating it over and over. I think we can sing all the stanzas if they’re so short and…

Crystal: The Spirit was moving me to keep going like that.

Jonathan: Oh, okay. Well, the Spirit told me doing all the stanzas of “O For a Thousand Tongues” was okay, because at least the words were different and I wasn’t trying to phony up some emotional/religious fervor. And even with the introduction, the whole thing was over in, like, two minutes and thirty seconds. So I think we’re good.

Crystal: I’m sorry, I can’t work like this. You may have all those “degrees” and all those “lessons” and play those “instruments,” but I’m the boss, so you need to watch the time and be prepared to cut verses every week.

Jonathan: We’ll see how the Spirit leads, Crystal.

So anyway, the point of that conversation is that stanzas of hymns are not that long, and if you feel a time crunch to wrap them up sooner, the real time-guzzling culprit is probably going to be found elsewhere in the service.

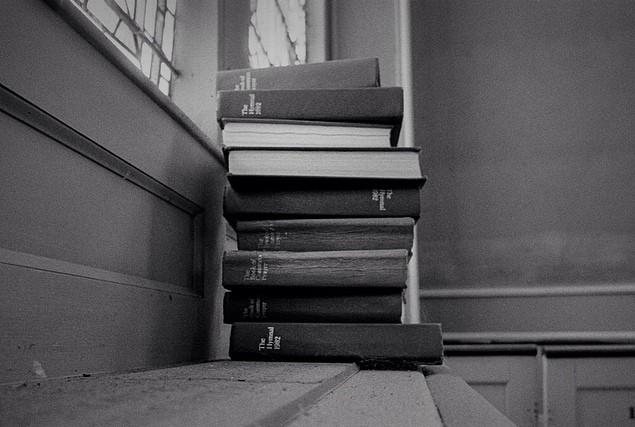

Now that we’ve blown the two categories of complaints out of the water, here are a few reasons for singing the whole hymn.

1. Skipping stanzas often destroys poetic and theological cohesion.

It’s important to keep in mind that what the hymnal contains is often a shortened version of the original hymnal. But hymnal committees generally do a good job presenting a text with a lucid flow between stanzas so that we get a cohesive poetic statement. In the best examples, omitting stanzas is theologically violent.

2. Skipping stanzas is awkward.

Even if you notate it in the bulletin, even if you announce it from the chancel, skipping stanzas always makes for one of those weird moments when the congregants look at each other with looks that say, “Are we really going to do this?” or “Is this the one we’re supposed to skip?” or “Which hymn number am I supposed to be on?”

Sometimes you even get one of those weird train wrecks in which everyone is singing something different. This could all be avoided quite easily by just singing the whole darn hymn.

3. Skipping stanzas is really not beneficial in any way.

With rare exception, it doesn’t save time and it doesn’t help the liturgy.

If the people you serve struggle to understand why we sing hymns, and why we usually sing the entire hymn, there’s an opportunity for pastoral instruction and leadership, not reluctant accommodation. I think the idea of omitting stanzas likely arose from the overriding pragmatism of the previous generation, which ultimately valued felt needs of the people over liturgy, symbol, and mystery.

It’s time to reevaluate this practice, and help our people return to finding the reward that comes with liturgical discipline.