I was going to call this post “How to Make a Beautiful Hymn Ugly,” but I decided to soften it a little. The hack job wielded upon this lovely hymn doesn’t make it ugly, only a little uglier.

I’ve long loved to sing the hymn “Sing Praise to God Who Reigns Above” since I broke away from my pop worship roots in graduate school. I still think ultimate line in each stanza, “To God all praise and glory,” is one of the most thrilling to sing in all of hymnody.

Most hymnals include four stanzas, except most Lutheran hymnals. God love the Lutherans for not being afraid of singing a bunch of stanzas.

As most translated hymns go, there were quite a few variations in the text of this hymn from its first English rendering in the mid-19th century, until around 1950, when the variations became fewer, and we were left with a few more or less standard versions.

Until the past few decades, when heavy-handed hymnal committees began to jack around with beloved hymns to make them sound more modern and inclusive. This is not the most dramatically altered hymn text, but one particular change stood out to me as I was reading through it this week, and it got me thinking about the rest of it.

The hymnal I was using was a newer publication from a mainline Protestant denomination. This is how the first stanza of “Sing Praise to God Who Reigns Above” appeared two hymnal revisions ago, in the mid-1950s, and the changes made in the current revision:

Sing praise to God who reigns above,

The God of all creation,

The God of power, the God of love,

The God of our salvation;

With healing balm my soul He fills is filled,

And every faithless murmur stills stilled:

To God all praise and glory.

I get it, we all use passive voice is used by all of us, but it doesn’t make for beautiful poetry. Quite the opposite, actually. It’s uglier. In this case it’s awkward, it doesn’t sing particularly well, and it obscures the identity of who is performing the action, who happens to be Almighty God. It’s a curious choice, too, considering this hymnal doesn’t eliminate every single masculine pronoun used for God the Father. Many beloved texts remain unchanged, such as this one:

“O my soul, praise him, for he is thy health and salvation!”

So is it because one hymn is more beloved than others? Or was the committee bored with their tedious busywork by the time they considered it? I don’t know. So why would you choose to make one text uglier? Particularly when Jesus himself taught us to pray using the locution “Our Father.”

Consistency aside, this is a classic case of scholars creating problems and doing their best to convince us all that we share those problems. And while I am sympathetic to the pastoral concerns that arise for some by referring to God as Jesus taught, those pastoral concerns do not give us license to rewrite the whole book.

The madness continues in stanza 2:

What God’s almighty power hath has made,

His God’s gracious mercy keepeth;

By morning glow or evening shade

His God’s watchful eye ne’er sleepeth;

Within the kingdom of His God’s might,

Lo! all is just and all is right:

To God all praise and glory.

Everyone knows what “hath” means. Again what are we afraid of exactly? Particularly when “keepeth” and “sleepeth” are kept unaltered.

And then there’s the great pronoun debate that has raged on through the past, um, five minutes, basically. If God is Father, we can use male pronouns with the understanding that such language is, in a sense, metaphorical. God is not male as I am. But the imminence of God as so wonderfully described by this hymn is left incomplete if we neuter Him, especially considering the shortcomings of the English language.

Plus, the edited version sounds ugly and weird. The original repetitions of the word “God” in stanza one are clearly for rhetorical effect: “the God of power, the God of love, the God of our salvation” refers to the God mentioned in the incipit. It is a categorical unpacking of the first use.

The newly added repetitions of “God” in stanza two are different. People don’t talk like this, and they shouldn’t write poetry like this, either. For instance, my dog has been active in the past few minutes while I’ve been writing this post. Let me tell you about it.

My dog ate food and drank water.

Then my dog barked at the back door.

Next my dog went outside to relieve my dog’s self,

And while my dog was out there,

My dog rolled in excrement left by the neighbor’s cat.

My neighbor’s cat is not a very good cat.

My neighbor’s cat likes to leave my neighbor’s cat’s excrement in my backyard for my dog to find.

Now I have to give my dog a bath because my dog has grass and dirt and cat excrement in my dog’s hair.

See. Weird. And awkward.

Stanza three is more of the same:

The Lord is never far away,

But, through all grief distressing,

An everpresent help and stay,

Our peace, and joy, and blessing;

As with a mother’s tender hand,

He God gently leads His own, His the chosen band:

To God all praise and glory.

And finally, stanza four:

Thus, all my toilsome way along,

I sing aloud Thy praises,

That men all may hear the grateful song

My voice unwearied raises;

Be joyful in the Lord, my heart,

Both soul and body bear your part:

To God all praise and glory.

This change doesn’t bother me as much in this particular context. By “men,” it’s clear we mean everyone hearing my voice as I sing God’s praises. In other hymns, such a change, particularly when oft-repeated, can be quite jarring and end up meaning something other than the author intended.

While most of us in the past few decades have been trained to write with inclusive language, and to not say “men” unless we are talking about male persons, it’s okay to acknowledge that this was not always the case, and to preserve the beauty of the poetry. Here is what one woman, Episcopal Priest Fleming Rutledge, says about this predicament in the forward of one of her books:

“I have generally avoided the use of ‘man’ and ‘him’ in my more recent work, but I am not fanatical about it. If I value the cadence of a sentence, or the time-honored use of a term (for instance, ‘the old Adam’), I will retain the old form.”

Maybe we shouldn’t be fanatical about it, either. And it is certainly fanatical when we’re singing to and about a beautiful God to make those hymns distinctively less beautiful.

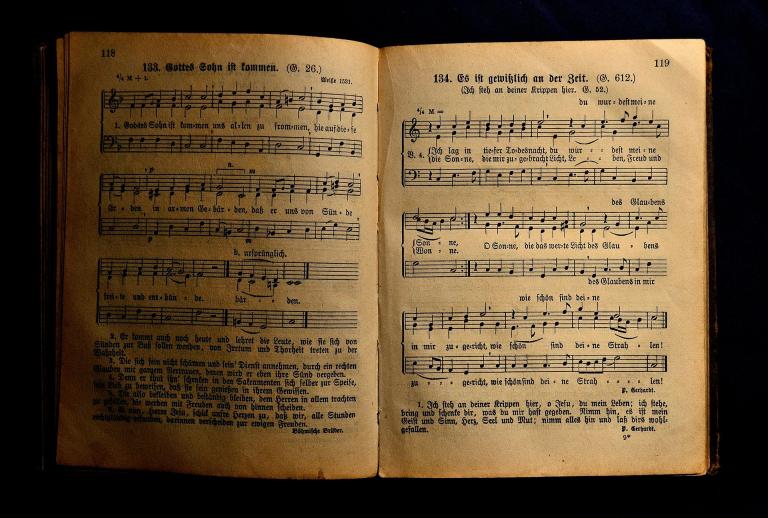

Photo:

pixabay, creative commons 2.0