“‘Mr. DeMille,’ said [Charles] Laughton, ‘I notice that all of your pictures have a religious motif. Are you yourself very religious?'” “‘Well,’ said DeMille, ‘I suppose there’s a little bit of God in DeMille and a little bit of DeMille in God'” (291).

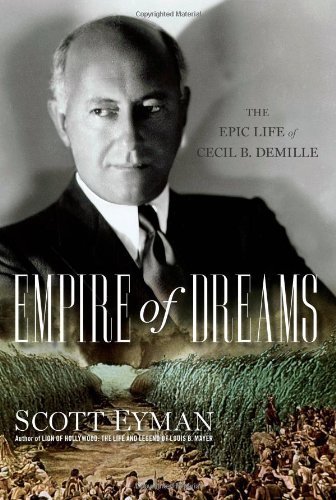

Few Hollywood biographers and historians are as insightful as Scott Eyman. Having tackled such giants as Louis B. Mayer and John Ford, Eyman turns his attention to Cecil B. DeMille for his latest project. The result is Empire of Dreams: The Epic Life of Cecil B. DeMille, a book every bit as fascinating and complex as the man on which it is based.

Early in his book, Eyman recounts a quote about DeMille from film historian, scholar, and archivist Kevin Brownlow: “‘He directed as if chosen by God for that one task'” (5). Of course, as with all divine callings, the road to that eventual vocation wasn’t paved with gold…even if pots of gold awaited him upon his arrival. Eyman devotes significant attention to DeMille’s career as a struggling actor and playwright and the complicated relationships with his father, mother, and brother during those difficult years. It was during this time, however, that he would meet his wife Constance with whom he fell madly in love and began a unique (and that’s putting it lightly) relationship that would last their entire life. Like many early filmmakers, DeMille came into the business out of both happenstance and necessity. Unlike other filmmakers, however, he took to the business like a duck to water and began a career in silent movies that would continue into sound and color films well into the 1950s.

Once DeMille settled into his filmmaking career he proved to be both a shrewd cinematic politician and economist. Eyman provides an in-depth look into his cutthroat relationships with fellow film pioneers like Samuel Goldwyn, Jesse Lasky, and Adolph Zukor. These relationships, often fraught with disagreements and betrayals, eventually lead to the foundation of Paramount Studios, whose both early and lasting successes can be attributed to DeMille. While the contemporary film world might be dominated by men, it has not always been so. The silent film era was particularly kind to women in that there were many more women in prominent positions of filmmaking from writing to directing to editing, not to mention wardrobe and set design. DeMille owed much of his success to women, particularly Jeanie MacPherson, who wrote many of DeMille’s most famous films. Eyman writes, “In most cultural and religious respects, DeMille was egalitarian, promoting women into positions of power and influence very early in his career and displaying no noticeable prejudices about homosexuals” (102).

Unbeknownst to many viewers, DeMille directed wildly successful films before his entree into biblical epics with The Ten Commandments in 1923. Most of these were “bedroom dramedies,” sophisticated and scandalous examinations of marital life at the turn of the century and early experiments with themes of sex, violence, and decadence that would explode onto widescreens decades later with his biblical epics. Eyman observes, “DeMille started his comedies where most directors end them–with marriage” (151). These films often featured a married couple in something of a slump and in order to liven things up either the husband or wife would look for romance on the side. These extramarital affairs would either split the couple up for good or make them realize their love for and need for one another and drive them closer together. In many cases the eventual “punishment” for this behavior would serve as the moral antidote (conclusion) to the immoral acts in which the film would revel for the majority of its screen time.

These films almost certainly satisfied a transgressive desire on the part of moviegoers bound by Victorian mores at the turn of the century. Many of DeMille’s staunchest critics, then and now, accused DeMille of simply pandering to the baser desires of his audiences. Yet, after reading Eyman’s biography, it seems much more complex than that. In a way, it’s as if DeMille simultaneously gave the public what it wanted while making them want what he had to give them. This is certainly the case with his biblical epics which satisfied both a popular American Christian piety and the desire for those things (sex, luxury, and violence primarily) that that piety prohibited. Eyman sums up DeMille’s relationship with both critics and audiences: “[…DeMille] also realized that in a business like the movies, if you can’t have both critics and audiences, hope for the audience.” (364)

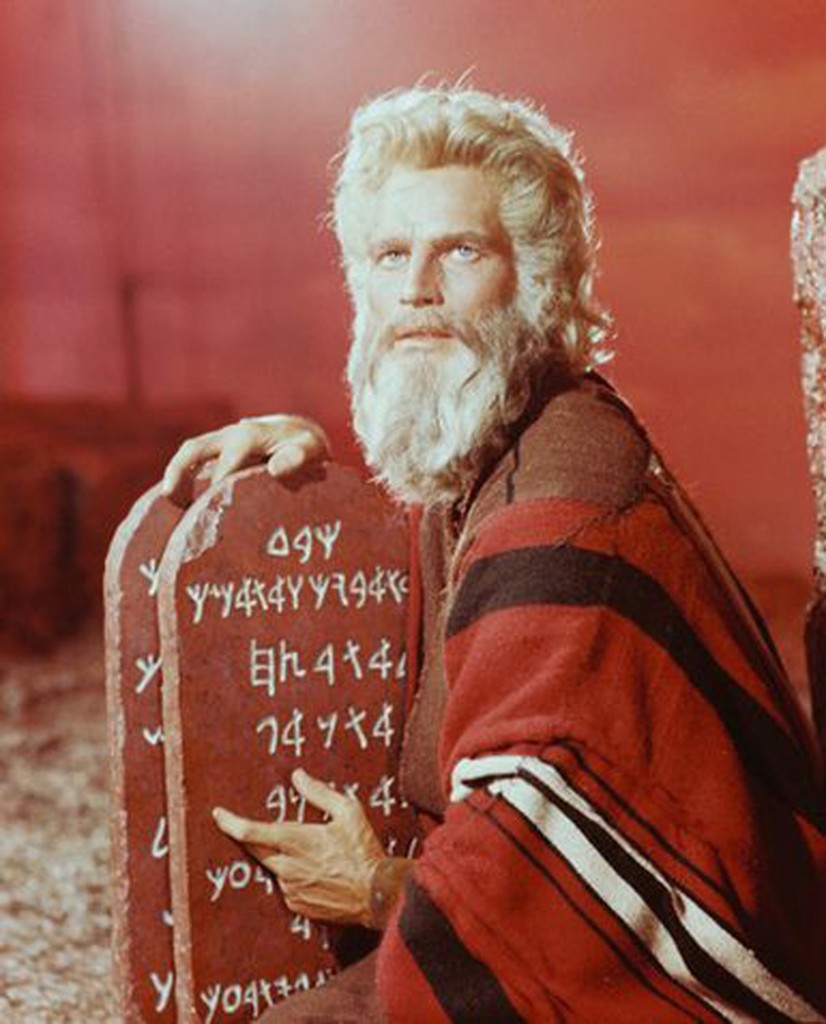

Despite his sophisticated silent films, DeMille is best known for his biblical epics which included two versions of The Ten Commandments (1923 and 1956), The King of Kings (1927), The Sign of the Cross (1932), and Samson and Delilah (1949). In fact, when asked to sum up his career, DeMille picked three of these to do so, The King of Kings, The Sign of the Cross, and The Ten Commandments (1956). Behind-the-scenes incidents and on-screen images from these films reveal both DeMille’s scandalously sacred approach to religious narratives and changing relationships that censors, critics, and audiences had with these narratives from the 1920s to the 1950s.

For the former, one need look no further than the introduction to The King of Kings in which a highly sexualized Mary Magdalene teases her courtiers and expresses frustration that Jesus has stolen her man, Judas, away from her. DeMille knew that audiences would flock to see a film about the life of Jesus, but he hooked them with the scantily clad Magdalene. In terms of the latter (changing opinions of religious narratives), consider behind-the-scenes events in the production of The Sign of the Cross and Samson and Delilah. Few of DeMille’s films so explicitly telescoped his obsession with the scandalous and the sacred as The Sign of the Cross. His stubborn refusal to cut any of its offensive images, like Claudette Colbert’s milk bath, upon its initial release put him at odds with many censors and religious leaders of the day but certainly not his audiences.

When DeMille began pre-production of Samson and Delilah, Paramount Studios expressed reservation with releasing yet another biblical epic. All those fears quickly disappeared after DeMille showed them the abbreviated costumes that Heddy Lamarr would wear as one of the film’s titular characters.

However, few of the stories that Eyman recounts are as telling as an exchange that DeMille had with his brother William during pre-production of The King of Kings. When the two disagreed over a narrative decision that DeMille planned to make, William said, “‘They [audiences] are not going to believe it anyway just because they see it on the screen.'” “‘Yes, they are,’ shot back Cecil. ‘If you printed 75 million Bibles, their idea of the life of Jesus Christ is going to be formed by what we give them. This next generation will get its idea of Jesus Christ from this picture'” (233). In this exchange, Eyman shows us that DeMille, unlike few other filmmakers in the history of the business, understood the power of film to effect religious consciousness. And the audience certainly got it. One American minister, years after The King of Kings‘ initial release, approached H. B. Warner, the actor who played Jesus, and told him that every time he thinks of Jesus, he sees his face. It’s not too much of a stretch to say that, for generations of moviegoers, the same could be said for Charlton Heston as Moses.

It’s difficult to overstate DeMille’s place in the history world cinema. Eyman writes, “[…He] embodies the story of the American motion picture and its rise to world preeminence” (10). It’s equally difficult to overstate the brilliance of Eyman’s book. Few filmmakers could be more difficult to “capture” than DeMille, and it seems impossible to do so any better than Eyman has done here. While there are countless texts left to be written on the work of Cecil B. Demille, Eyman’s book is currently the definitive work on his life and will no doubt remain so for many years to come. Eyman portrays DeMille for what he was, a masterful storyteller, a brutally demanding director on set, an unforgettably kind and faithful friend behind the scenes, and a deeply flawed human being who could tell stories better than most. Lest we be too quick to judge DeMille’s contradictions (hypocrisy), we should remember our own. Lest we dismiss many of his films, we should consider the schlock that fills many of our cineplexes today, the majority of which are aesthetically and narratively inferior to even DeMille’s worst. Eyman’s book benefits from a wealth of interviews with DeMille’s contemporaries that he has conducted throughout his career. Film history buffs or readers interested in religion and film would do well to explore this engrossing account of a man who ultimately gave his life to his craft.