As I revel in my return to the Bay Area, I continue to catch up on classics that have to do with San Francisco. Last weekend I rewatched The Maltese Falcon (1941). Truth be told, the film version, based on the Dashiell Hammett novel, could have taken place anywhere. Other than some stock footage of San Francisco, the place names, and “view” of the Oakland Bay Bridge behind Sam Spade’s desk, the city doesn’t play much of a role. It’s still a classic.

As I revel in my return to the Bay Area, I continue to catch up on classics that have to do with San Francisco. Last weekend I rewatched The Maltese Falcon (1941). Truth be told, the film version, based on the Dashiell Hammett novel, could have taken place anywhere. Other than some stock footage of San Francisco, the place names, and “view” of the Oakland Bay Bridge behind Sam Spade’s desk, the city doesn’t play much of a role. It’s still a classic.

The head-scratching plot begins with the classic private investigator setup of a mysterious dame, Ruth Wonderly, or Brigid O’Shaughnessy, or whatever name she’s using that day, (Mary Astor) walking into Sam Spade’s (Humphrey Bogart) office with a sob story. Her sister has run off with a brute named Floyd Thursby. Spade’s horny partner, Miles Archer (Jerome Cowan), looks her up and down and decides to take the case. He is supposed to shadow Thursby after “Ruth” meets with him later that evening in order to find the sister. But it doesn’t work out that way. That night, both Archer and Thursby are killed. Before long, two police investigators are knocking on Spade’s door asking if he was involved in either of the killings. He’s been having an affair with Archer’s wife, which means he could have killed Archer to get at her, or maybe he killed Thursby for killing his partner Archer.

The murders and the mysterious woman—Ruth or Brigid or whatever her name is—turn out to be part of the greater mystery of the Maltese Falcon. The bird is a priceless piece of art, fabled to be covered in gold and jewels, sent by the Knights of Malta to the King of Spain sometime in the sixteenth century. It turns out Brigid and Thursby, along with some international treasure hunters Kaspar Gutman (Sydney Greenstreet), Joel Cairo (Peter Lorre) and a hired gunman Wilmer Cook (Elisha Cook, Jr.) are all trying to get their hands on it.

Confused? You should be. Fortunately there’s a lot to enjoy in the film even if you can’t quite nail down the plot. The character performances, especially Sydney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre, are worth watching in themselves. The Maltese Falcon is also one of the quintessential Bogart films, as the short sparkplug of an actor delivers lines in his run-on, spitfire style: “You won’t need much of anybody’s help. You’re good. Chiefly your eyes, I think, and that throb you get in your voice when you say things like ‘Be generous, Mr. Spade.'”

The Maltese Falcon is a not so much a genre film as a created-the-genre film. So many elements of film noir came from this first directing effort by John Huston: the femme fatale, the gumshoe plot full of mysterious characters and red herrings, the rapid-fire dialogue, and maybe, most importantly, the MacGuffin.

The MacGuffin is the thing that everybody wants in the film that drives the plot. It doesn’t matter what the MacGuffin is, as long as it matters to the characters. J.R.R. Tolkein produced a massive fantasy work, which Peter Jackson turned into three massive fantasy blockbusters, based on one small “precious” MacGuffin. J.K. Rowling seemed to have relied on some sort of MacGuffin-generating machine for the Harry Potter series. I counted at least a dozen in the final book and movies.

But the Maltese Falcon is the original MacGuffin. And in Hammett’s story, it’s the thing all the supporting characters have been after for years. When they finally find a statuette that is supposed to be the Maltese Falcon and it turns out to be a fake, Gutman and Cairo seem almost giddy at the thought of continuing their worldwide chase for the real thing. The search has given their lives meaning.

These two characters bring us to the film’s extensive homoerotic subtext. Film critic Armond White has suggested that the true MacGuffin in The Maltese Falcon is Humphrey Bogart. We know all the women—Archer’s widow, Ruth/Brigid, and Spade’s secretary Effie (the magnificent Lee Patrick)—want to get their hands on him. But the men seem to want him too.

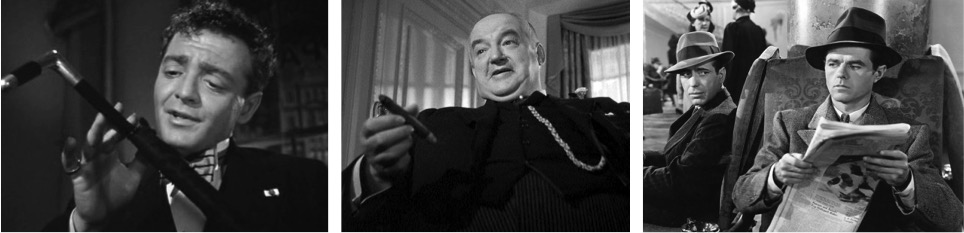

It doesn’t take much to see through the Hays Code smokescreen to figure out the Peter Lorre character is gay. He minces about in his fussy suit and smells of gardenia perfume. As he describes the lost Maltese Falcon to Sam Spade, he suggestively touches his umbrella handle to his lips. Spade seems amused by Cairo, but nevertheless physically brutalizes him several times, suggesting elements of BDSM: “When you’re slapped, you’ll take it and like it!”

Greenstreet plays Gutman as more of the bawdy, lusty gay around Spade: “I’ll tell you right out, I am a man who likes talking to a man who likes to talk,” he says, delighting in sharing drinks and cigars with Bogey. Gutman’s Boy Friday is his weak, ineffectual “enforcer” Wilmer Cooke, whose name sounds like “Wilma” in Bogey’s New York-ese. If Sam Spade is amused by Cairo, he is creeped out by Wilmer. Noticing Wilmer is shadowing him, Spade “outs” him to a hotel detective with suggestive language: “Why do you let these cheap gunmen hang around here with their heaters bulging out their clothes?”—almost like Wilmer is a priapic stalker. Later, he refers to Wilmer as a “gunsel,” which is a term for a punk or kept boy. By the end of the film, Spade has so bullied Wilmer that the gunsel is in tears.

So what is it about the MacGuffin? The standard Christian interpretation is that its idolatry–the things we chase after instead of God. My, how these characters search and search for this thing that gives their life meaning, when the meaning should really come from God! If I was a certain kind of Christian, I would say everyone has a God-shaped hole in their heart and that they’ll try to fill it with any kind of substitute until they find the real answer.

But I’m not that kind of Christian. I will cop to the notion that many, perhaps most of us, spend our lives chasing after things that don’t matter. But there’s no God-shaped hole in your heart. If there is, you ought to see a cardiologist.

What you need is already there. Getting in touch with God or the Spirit or the Source comes as part of the standard operating equipment. You just have to tune it to the right channel. Sometimes you can find yourself resonating with it through meditation or prayer or ritual or art. Sometimes you need to work on finding it alone, and sometimes you need a pastor, or a spiritual guide, or a community. But it’s there, just waiting to be uncovered.

If this sounds like wooly-headed liberal religion, I take my cues from that other flake, the one quoted in Luke 17:20-21: “And when he was demanded of the Pharisees, when the kingdom of God should come, he answered them and said, ‘The kingdom of God cometh not with observation: Neither shall they say, Lo here! or, lo there! For, behold, the kingdom of God is within you.'”

The kingdom of God is within you. You can stop searching for MacGuffins and following red herrings in the plot of life and find what you need within, both through your own spiritual practice and with the help of supportive community. That, in the words of Bogey, is “the stuff that dreams are made of.”