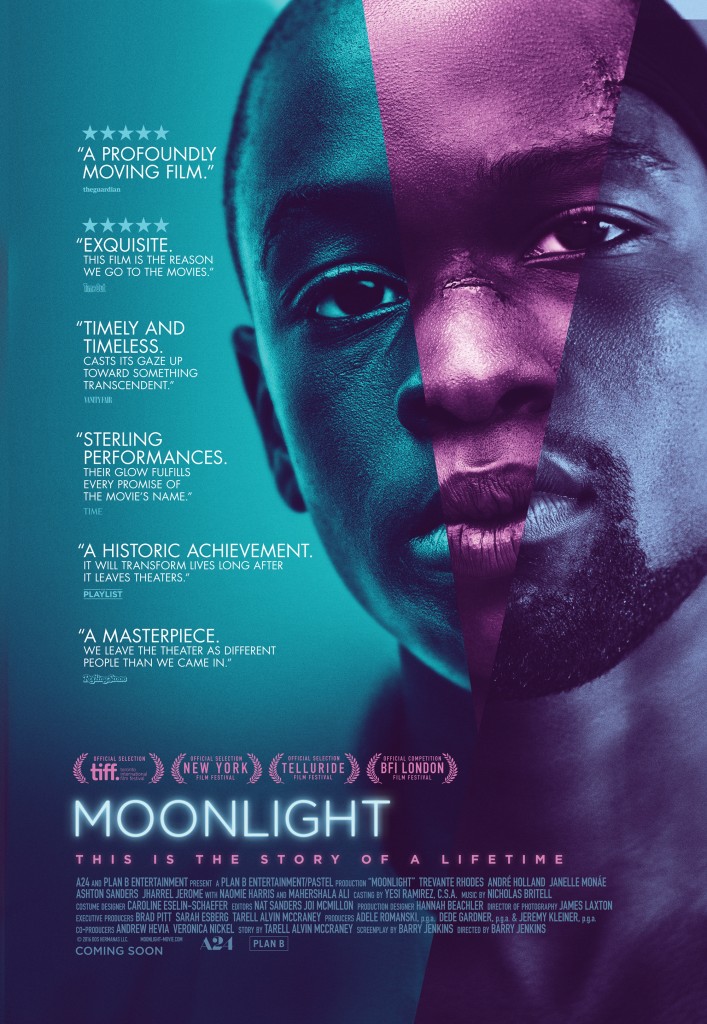

Moonlight has been receiving critical buzz since its debut at the winter film festivals last year, some of which has resulted in a Golden Globe for best picture (drama) and a slew of Oscar nominations. Written and directed by Barry Jenkins, based on a play by Tarell Alvin McCraney, it is a rare film that features black men being at turns tender and melancholy, crushed and resilient, without the usual Hollywood fetishization as thugs or sex machines. Tracing the coming of age of one black boy, Chiron (pronounced shy-RONE) from grade school to high school to young adulthood, it might have been called (Black Queer) Boyhood.

Moonlight has been receiving critical buzz since its debut at the winter film festivals last year, some of which has resulted in a Golden Globe for best picture (drama) and a slew of Oscar nominations. Written and directed by Barry Jenkins, based on a play by Tarell Alvin McCraney, it is a rare film that features black men being at turns tender and melancholy, crushed and resilient, without the usual Hollywood fetishization as thugs or sex machines. Tracing the coming of age of one black boy, Chiron (pronounced shy-RONE) from grade school to high school to young adulthood, it might have been called (Black Queer) Boyhood.

Set in three distinct acts, Chiron as a young boy (Alex Hibbert) lives in Miami, is bullied by kids at school and neglected by his crack-addicted mom (Naomie Harris). Chased by taunting school kids and unable to go home, he finds himself one night in the care of a drug dealer named Juan (Mahershala Ali), and his girlfriend Teresa (Janelle Monáe). In a moving exchange over dinner, he asks Juan what a faggot is—the term boys were using to bully him at school. In a surprising response, Juan gently tells Chrion faggot is a term used to hurt gay people. Chrion follows up by asking, “Am I a faggot?” Again, Juan surprises not by trying to proscribe the boy’s identity, but to say if he is gay, he’ll know one day, and he should never let anyone call him faggot.

In Act II, we see Chiron as a teenager (Ashton Sanders). His mother has spiraled further into addiction, even hitting him up for money to try to get her fix. Things have barely changed for him at school, except the bullying boys are bigger and more dangerous. Chiron has a friend, Kevin (Jharrel Jerome) who seems to be able to bring the quiet boy out of himself. One sultry night they drive to the beach together and have an intimate and beautiful moment of sexual exploration. But the spell is broken the next day when another boy gets Kevin to participate in a brutal game of “knock down/stay down.” Kevin punches Chiron, and as Chiron gets back up again, the boys continue to beat him until he falls to the ground to be pummeled and kicked within an inch of his life. Betrayed by his friend and at the end of his patience, Chrion answers with violence, and is sent to juvenile detention.

Chiron as a young adult (Trevante Rhodes) is nearly unrecognizable. Out of juvie and muscled up, he has built an armor of flesh around himself and become a drug dealer. But we can still sense Chiron’s sensitivity, and we get the idea he is still looking for himself. His mom is in rehab and is making slow progress toward getting her life back. Out of the blue, he gets a call from Kevin in Miami, and he goes to see him.

Based on the violent end of their school friendship, we’re not sure at all what Chiron wants from Kevin. Kevin has become a cook at a diner. The meeting between them seems both dangerous and flirtatious, as Kevin fixes Chiron a sumptuous Cuban feast of chicken and black beans and rice. What happens next between the two is remarkable, and not at all what you might expect from their reunion. We learn that underneath his learned street bluster, Chiron still has the passion and thoughtfulness he had as a child.

Although I have to be careful in appropriating stories like this for my theological ramblings, I’d like to say Chiron is a Christ figure. In a gorgeous scene early on in the film, Chiron undergoes a baptism in the ocean in which he learns to lay back and trust the supporting arms of Juan, as imperfect a character as he is. The betrayal of Kevin and Chiron’s subsequent beating at the hands and feet of the adolescent mob bears a strong resemblance to the Christ story. Where it differs, however, is in his story as a young adult. Set up by society for failure, headed for a life of violence and early death or years in prison, his reunion with Kevin is the beginning of him reclaiming his own life story. Rather than playing out Hollywood and America’s myth of redemptive violence, which has always required the nearly ritualistic sacrifice of young black men, Chiron steps down off the cross like Jesus in The Last Temptation of Christ. He refuses to play out the final act.

I’m also reminded that Chiron’s name is spelled the same as the mythical Greek centaur who was quiet and perceptive, misunderstood by his peers. At one point he is shot by an arrow from Hercules, and although he wishes to die because of the pain, he cannot, because he is immortal. It is from his suffering that he goes on to become a mentor to great figures like Achilles, and introduces medicine to humankind.

Moonlight is based on an unproduced play called “In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue”. The film is beautifully shot by cinematographer James Laxton, and he captures these rich moments of blueness and greenness in the Miami twilight. Despite its seriousness, the film has a luminous quality that at times brings a sense of lightness and transcendence.

But the “blue” of the title also has to do with a depth of emotion we rarely get to see in Hollywood films from characters who are poor and/or people of color. As playwright Terrell Alvin McCraney says, “It’s probably under the moonlight that we see that black boys can be blue, can be sad and sullen and intimate,” he said. “It’s under starlight that we see them differently, or that we get the chance to.”