I haven’t reached Exodus yet, but Greg Thornbury has alerted me and other read-the-Bible-through-in-a-year readers that Moses and the exodus are important. In fact, without an actual historical figure such as Moses and real historical event such as the exodus narrative, the integrity of the New Testament is up for grabs:

. . . if the scholars are right that is: “No Jews in Egypt means no Exodus. No Exodus means the foundation of Judaism is a myth. And for Christians it means that Jesus Christ and the writers of the New Testament got it wrong because they all accepted the reality of Moses and the Exodus and built their teachings on them.”

That’s precisely right. At several points in the Gospels, Jesus refers to Moses and his commandments as though Moses really wrote them. At the Last Supper, Jesus connected his physical death—blood and body—with that of Moses’ Passover Lamb sparing the life of the Israelites during the Plague of the Firstborn. Did Jesus predicate his own sacrificial death on the cross upon an event that never occurred? If that is the case, the entire covenantal nature of the biblical narrative falls apart. Jesus of Nazareth cannot be “the new Moses” if Moses never existed.

The idea of the exodus never having happened surely would throw a wrench into the formation of both ancient and modern Israel. And the ties between the Old Testament narratives and Christ are certainly worth highlighting in any attempt to discredit the Old Testament.

But Thornbury may go an inference too far when he worries what turning Moses into myth will do to the United States:

Not only does Christian faith rest squarely on the historicity of the Moses account. So does the foundation of law and order in Western society. Our traditions of common law and jurisprudence go back to Jewish notions of covenant. Without Moses, we lose divine sanction for limits on government and the power of human authorities. What is the goal of this constitutionalism rooted in Torah? According to the Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court, it “seeks to prevent tyranny and to guarantee liberty and rights of individuals on which free society depends.” Everyone who cares about liberty, then, has purchase in the debate over Exodus. Were the teachings of Moses from Moses? Were they rooted in a transcendent source? Those are some pretty important questions.

This is apologetic overreach and suspicious history. Paying attention to the pagan Greeks and Romans sure would seem to make sense of the form of government that the American founders created. The Hebrews knew something about monarchy (though their experience with it was not pretty). But Moses and the prophets were not exactly proficient in republicanism, constitutions, or federalism. Perhaps the best indication of the difficulty involved in tying biblical covenant theology to modern liberal societies comes from the Puritans, those almost-Americans who had the largest Israel complex of all European settlers in North America. The Puritan understanding of the covenant was not much of a guarantee to the freedoms or rights of Roger Williams or Anne Hutchinson (for starters), both of whom had to leave Massachusetts Bay for holding views contrary to the established authorities.

I wish Thornbury had quit while he was ahead. The implications of turning Moses into mythology are sufficiently high for the authority and infallibility of Scripture. Why would he feel the need to lower the stakes by raising such ephemeral matters as the affairs of princes whom the Bible tells us not to trust.

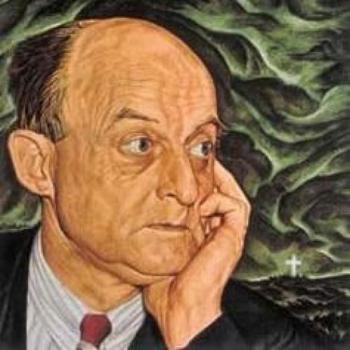

(Image: Moses Trampling the Crown)