(For some background on intergralism vs. liberalism, see this and the links included.)

Rod Dreher seems to be convinced that First Things magazine has run out of steam. The idea of harmonizing Roman Catholicism and the American political tradition, once very attractive, is no longer viable.

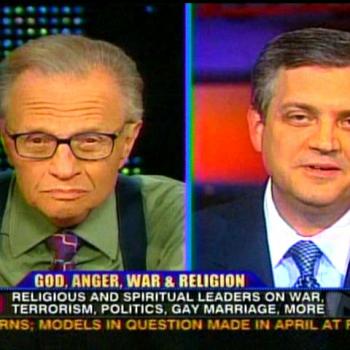

First Things burst onto the world in 1990. Its editor-in-chief, Richard John Neuhaus, was a Catholic priest and a convert, but he had a broad and generous ecumenical vision. He and his co-founders wanted the magazine to become home to Catholics, Protestants, Orthodox, and Jews who were interested in the intersection of religion and public life, and who wrote from a morally and theologically conservative perspective. First Things became the most important journal of its kind, a real flagship for small-o orthodox Christian thinkers.

It’s mission, in other words, was civic Christianity (according to Michael Hanby):

Broadly speaking, we may characterize the civic project of American Christianity as the attempt to harmonize Christianity and liberal order and to anchor American public philosophy in the substance of Protestant morality, Catholic social teaching, or some version of natural law that might qualify as public reason.

Integralists are generally speaking Roman Catholics who have rejected American civic Christianity. They advocate in some fashion “the idea that there should be a closer formal relationship between the Catholic Church and the State, whose governing principles should be consonant with Catholic teaching.”

Almost fifteen years ago, this was a point that Damon Linker made in his book, Theocons. He was not advocating more religion in politics but expressing alarm at that amount of Christianity that civic Christianity was foisting on the nation’s politics. He was an American who agreed (implicitly) with integralism, namely, that Roman Catholicism is incompatible with American politics. The odd thing about Linker’s argument was that he thought Neuhaus and other figures associated with First Things, the ones responsible for an American civic Christianity, were closet integralists. That point came out in an exchange between Linker and Ross Douthat at The New Republic.

The nub of Linker’s point was that all believers who belong to the American political community have to make a “liberal bargain” to obtain membership:

Is my opposition to theoconservative ideology not better understood as opposition to orthodox Catholicism? Can you and Neuhaus, as Catholics, be good citizens of a liberal polity like the United States?

My answer is simple: Of course you can–on one condition. Like every other citizen, you must be willing to accept what I call “the liberal bargain.” In my book, I describe this bargain as the act of believers giving up their “ambition to political rule in the name of their faith” in exchange for the freedom to worship God however they wish, without state interference. What does this mean, in practical terms? It means that your belief in what the Roman Catholic Church believes and teaches is irrelevant, politically speaking. It simply shouldn’t matter whether or not you think that justice has a divine underpinning, anymore than it should matter whether you prefer Jane Austen to Dostoevsky. In a word, liberal politics presumes that it’s possible and desirable for political life to be decoupled from theological questions and disputes.

That is a bargain that integralists and Benedict Option folks like Rod Dreher are unwilling to make.

But in the exchange with Linker, Douthat did not think this was the only way to understand the bargain. To counter Linker, Douthat invoked Neuhaus and the folks at First Things:

while I understand that you disagree with and dislike Neuhaus’s public philosophy, I’m baffled by the suggestion that religiously-grounded political worldviews are required by the liberal bargain to cede the field to their secular competitors. American history is rife with competing public philosophies, and I’m uncertain why we would be better off if, say, the Christianity-infused partisans of the Social Gospel (a “far more comprehensive” religious ideology than anything Neuhaus has proposed) had simply conceded defeat to the less-religious, more scientific partisans of Social Darwinism, on the grounds that the Social Gospel’s explicitly Christian ideology had no place in public life. (I don’t see why I need to prefer the eugenics movement to William Jennings Bryan just because Bryan talked God and the eugenicists talked “reason.”) By the same token, I don’t see why religious conservatives in the 1970s, faced with an ideologically driven transformation of a number of fundamental American institutions, should have simply sat back and quietly accepted the complete social renovation of their country–because, hey, that’s what the “liberal bargain” requires.

I know I’m harping on history a bit here, but I really thought that The Theocons’s greatest weakness was its refusal to grapple with the complexities of the American past in any detail–as if Neuhaus and his compatriots had emerged from nowhere, rolling the apple of religious discord into a secular Olympus. If you had simply made the argument–which you did make, and make again in your response to my first post–that Neuhaus’s Catholicism is ill-suited to serve as our national public philosophy, because not enough people are likely to accept it, then you might have persuaded me. …But you couldn’t just say that the “theocons” are out of step with America and leave it at that…

If you’re the arbiter of what the liberal bargain means, then I want no part of it. The American experiment has succeeded for so long precisely because it doesn’t force its citizens channel their “theological passions and certainties … out of public life and into the private sphere.” It forces them to play by a certain set of political rules, yes, which prevent those passions and certainties from creating a religious tyranny. But it doesn’t make the mistake of telling people that their deepest beliefs should be irrelevant to how they vote, or what causes they support. The kind of secularism that you’re promoting–and that Neuhaus and the rest of the “theocons” were originally reacting against–is an attempt to change those rules and impose greater restrictions on religious Americans than have heretofore existed. This isn’t just blinkered, unfair, and contrary to the actual American tradition of how religion and politics interact; it’s also dangerous to liberalism, because it vindicates those people–Christians and secularists alike–who have always said that faith and liberalism aren’t compatible and that everyone need to choose between Christ and the republic, between God and Caesar. And, if you force Americans to make that choice, I’m not sure you’ll be happy with the results.

Where Douthat in 2020 is on this compared to 2006 is uncertain. But for Protestants the alternatives of harmony between the Roman Catholic Church and the state or Linker’s secularist reading of American politics are not appealing.