Short Prayers? What about the cross? What is the Theology of the Cross?

Short Prayers? What about the cross? What is the Theology of the Cross?

Then Jesus, crying with a loud voice, said, “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.” Having said this, he breathed his last. (Luke 23:46)

Dachau Reflections and the Theology of the Cross

It has been a few years since I last visited Dachau in Germany. At this town just outside Munich is located one of the thirty concentration and extermination camps operated by the Nazis during the Second World War. The Nuremberg indictment said that 5.7 million people, many of them Jews, had been taken from their walk of daily life and ushered into the camps by force. There they perished from starvation, exhaustion, gas chambers, or firing squads.

A visitor to Dachau today can walk the ground of the old camp. It is never crowded. No one rushes you. The crematoriums sit there silently. There is no conversation when you stand looking at an engraved marker which reads, “Here lie 30,000 unknown dead killed by firing squad.”

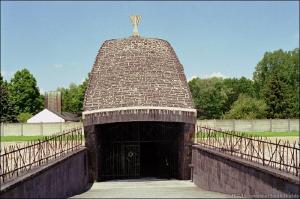

Distributed around the compound stand multiple chapels: one Jewish, one Catholic, one Protestant. The Jewish chapel hauntingly reminds one of a crematorium, a furnace of death. [Photo: Jewish Memorial]

Distributed around the compound stand multiple chapels: one Jewish, one Catholic, one Protestant. The Jewish chapel hauntingly reminds one of a crematorium, a furnace of death. [Photo: Jewish Memorial]

The Protestant chapel does not look like an ordinary church. It is just a small bare room. The bareness is broken only by a sculpture by Helmut Striffier. The sculpture consists of four massive cubes of steel built right into the front wall. The cubes are arranged so as to form a single larger cube. Their facing surfaces form a square. The narrow space between the four blocks of steel forms a natural cross. [Dachau, Protestant Chapel of the Atonement, Art by Helmut Striffier]

And in this cross-shaped space left by the giant cubes there is a contorted, barely recognizable, human figure. It is a man squeezed in between the massive chunks of steel. The cross and the contorted man, of course, remind us of the crucified Jesus. Simultaneously they remind us of those millions of innocent people—other Jews—who got caught under the giant wheels of an industrial war machine that simply rolled over and crushed everyone in its path. And this is not all we are reminded of. In other ways, perhaps less dramatically that sculpture symbolizes each one of our lives.

And in this cross-shaped space left by the giant cubes there is a contorted, barely recognizable, human figure. It is a man squeezed in between the massive chunks of steel. The cross and the contorted man, of course, remind us of the crucified Jesus. Simultaneously they remind us of those millions of innocent people—other Jews—who got caught under the giant wheels of an industrial war machine that simply rolled over and crushed everyone in its path. And this is not all we are reminded of. In other ways, perhaps less dramatically that sculpture symbolizes each one of our lives.

Two things are important in the Theology of the Cross. First, God is revealed under the opposite. Under cruelty and suffering, God is present with love and healing. Under dying and death, God is present with resurrection and life.

Second, just as Jesus feels the agony of abandonment and the despair of death, so also does God feel the agony and despair of you, me, and every estranged creature. We are never alone in danger, depression, or despair.

The Crush of the Cross and the Theology of the Cross

We find a similar sculpture adorning the Roman Catholic Chapel named, The Mortal Agony of Christ. Again, four heavy blocks of unforgiving steel frame a cross that crushes the Son of God and, hence, the sons and daughters of creation.

Those big heavy steel blocks represent powerful crushing forces, forces that are threatening to snuff out our dreams and to squash our enthusiasm. They represent the apparently invincible and insurmountable barriers that retard and block our efforts at achievement. They represent the verdict, “it’s cancer,” and a death sentence from which no pardon can be wished for. They represent the economic oppression of the world’s poor, unable to afford the food they need to live and unable to protect themselves from marauding bandits and rapists.

Those big heavy steel blocks represent powerful crushing forces, forces that are threatening to snuff out our dreams and to squash our enthusiasm. They represent the apparently invincible and insurmountable barriers that retard and block our efforts at achievement. They represent the verdict, “it’s cancer,” and a death sentence from which no pardon can be wished for. They represent the economic oppression of the world’s poor, unable to afford the food they need to live and unable to protect themselves from marauding bandits and rapists.

Let us look at those Dachau sculptures again. The cross is the point of convergence of the crushing pressures. Yet, it also defines the limits of those pressures. Like mortar that holds bricks apart while holding them together, the cross is the power which prevents its own elimination. Ironically, the cross symbolizes deliverance. In the case of Jesus, Good Friday’s crucifixion was superseded by Easter Sunday’s resurrection. Death was followed by new life. God made the difference.

As difficult as it may sound when confronted with the crushing weight of machines bent on human destruction, the cross reminds us that God too experiences our oppressive burdens. And, more: “God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong” (1 Corinthians 1:27b). And still more: “It is sown in weakness, it is raised in power” (1 Corinthians 15:43b).

PRAYER

O Crucified God, you feel the crushing weight of crosses too heavy to bear, strengthen us to bear our own cross through the promise of Easter. Amen.

▓

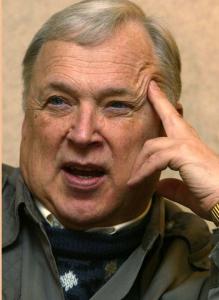

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. He is author of Short Prayers and The Cosmic Self. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Public Christian Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. He is author of Short Prayers and The Cosmic Self. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Public Christian Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

▓