Should Christian Transhumanism (CH+) be called Transhumanist Christianity (TC+)?

What is at stake?

H+ 9 / 1019. Religious Transhumanism

In this Patheos series on Public Theology, we have been interviewing adherents to religious transhumanism (Humanity Plus or H+) such as Micah Redding (evangelical Christian), Lincoln Cannon (Mormon), James “J” Hughes (UU), Michael LaTorra (Buddhism), Hava Tirosh-Samuelson (Judaism), and others. We have asked if we could enhance virtue technologically and whether Radical Life Extension or Cybernetic Immortality is more inviting than Resurrection of the Body (Peters 2019). In this post, we ask about the term, Transhumanist Christianity.

What appears clear is that something within the H+ vision of human evolution or better, transformation, resonates with our inherited religious sensibilities. One theologian in the Anglican tradition, Ian Markham, finds consonance between his Christian eschatological vision and the transhumanist vision of transformation. “Our goal remains the same—a life of virtue and a just society, where all are able to participate. Inspired by the promise of God’s kingdom, we are called to transform the present into what God always intended.” (Markham 2020, 190) Might the technological transformation promised by transhumanists cohere with the eschatological redemption the New Testament promises? If so, should this lead to a Christian Transhumanism or to a Transhumanist Christianity?

This newsletter is public theology in action and reaction. Public theology relies upon the dialogue between faith and science to develop a theology of nature. A theology of nature could offer critically valuable tools for understanding and explaining new challenges.

Christian Transhumanism (CT+) versus Transhumanist Christianity (TC+)

What appears before our eyes but may still be invisible is the relationship between adjectives and nouns. When “religious” is the adjective and “transhumanism” is the noun, then transhumanism bears the weight. Is this wise?

To date, the artificers of H+ have been secular, in many cases belligerently anti-religious. Transhumanists don’t feel a need to borrow what religious people have. “Transhumanism is a philosophy, a worldview and a movement,” proclaims Natasha Vita-More (Vita-More 2018, 5). Does this make H+ its own religion already?

To date, the artificers of H+ have been secular, in many cases belligerently anti-religious. Transhumanists don’t feel a need to borrow what religious people have. “Transhumanism is a philosophy, a worldview and a movement,” proclaims Natasha Vita-More (Vita-More 2018, 5). Does this make H+ its own religion already?

Zoltan Istvan, who ran as a candidate for the U.S. presidency in 2020 representing the Transhumanist Party, is a belligerent atheist. Anti-religious to the max.

To the extent that H+ offers an inclusive worldview, it is materialistic, atheistic, and anti-religious (Peters, The Ebullient Transhumanist and the Sober Theologian 2019). It is not uncommon for a transhumanist to claim that science and technology replace religion in the pursuit of the equivalent of salvation. “Religion promises but science delivers,” it is touted (Braxton 2021, 4). This leads to hubris. And hubris leads to colossal mistakes in anthropology. The most portentous of these mistakes is the underestimation of the enduring power of original sin.

So, terms such as “Religious Transhumanism” or “Christian Transhumanism” refer to something that currently does not exist. Nor could they exist, in principle. Why? Because some defining elements of H+ might turn out to be irreconcilable with theological anthropology and soteriology (Peters, Radical Life Extension? Cybernetic Immortality? Or, Resurrection of the Body? 2022c). Therefore, the term, “Christian Transhumanism,” might appear to some to be an oxymoron.

The public theologian asks: might intelligence enhancement as proposed by Elon Musk and his transhumanist friends contribute to Christian spirituality in the form of virtuous living, neighbor-love, holiness, sanctification, theosis, or deification? If the answer is in the affirmative, then we arrive a a transhumanist accent in Christianity.

How about “Transhumanist Christianity”?

Perhaps the term, “Transhumanist Christianity,” might better fit what Micah Redding and his Christian Transhumanist Association followers have in mind (Redding 2022). Under this banner, the Christian public theologian would engage the secular transhumanist in conversation, learning about the potential advances in AI (Artificial Intelligence), IA (Intelligence Amplification or cognitive augmentation), ML (Machine Learning), Superintelligence, the Singularity, and visions of a posthuman future. Like feeling the avocados on the supermarket shelf, the public theologian could then purchase or discard H+ produce for the Christian mission. It would be the Christian mission, not the H+ mission, that would provide the criterion.

Perhaps the term, “Transhumanist Christianity,” might better fit what Micah Redding and his Christian Transhumanist Association followers have in mind (Redding 2022). Under this banner, the Christian public theologian would engage the secular transhumanist in conversation, learning about the potential advances in AI (Artificial Intelligence), IA (Intelligence Amplification or cognitive augmentation), ML (Machine Learning), Superintelligence, the Singularity, and visions of a posthuman future. Like feeling the avocados on the supermarket shelf, the public theologian could then purchase or discard H+ produce for the Christian mission. It would be the Christian mission, not the H+ mission, that would provide the criterion.

Might we think of Transhumanist Christianity denominationally? Might it be akin to Orthodox Christianity or Baptist Christianity or Quaker Christianity? Or, might it better be thought of as an accent within Orthodox or Baptist or Quaker Christianity? If we already acknowledge conservatives and liberals, why not transhumanists too?

What do we mean by “Transformation”?

What does transformation mean for the Christian theologian? In his essay, “The Great Transformation,” the late Robert W. Jenson writes, “In its deepest aspect the Great Transformation is our entry into the life of the triune God” (R. W. Jenson 2002, 35-36).

The term, “transformation,” has to do with your and my relationship with God. It has to do with the translation from time to eternity. It has to do with purification, with the shedding of sin and taking up holiness. “The doctrine of theosis, the doctrine that our end is inclusion in God’s life, is not merely the brand of eschatology preferred by the Eastern churches; it names the only possible end of a creation, the only possible end of being that is history and drama” (R. W. Jenson 2002, 40-41) (Peters, Transhumanism and the Post-Human Future: Will Technological Progress Get Us There? 2011).

Some theologians fear the reductionism of secular H+. “The Satanic temptation of transhumanism is nested within the larger Western technologization of all of reality,” warns Eastern Orthodox theologian Brandon Gallaher. Like Jenson above, Gallaher invites us to the true and eternal transformation, theosis or deification. “There is another path and another vision than this nightmare: the pre-modern and pre-humanist vision of Godmanhood. It is to be hoped that this vision splendid might become more widely known and serve as a sort of check on the Luciferian fantasies of Mangodhood seen in contemporary transhumanism. But such a project of the dialogue of the ancient wisdom of Eastern Orthodoxy with modern technology, of Mt. Athos with Silicon Valley, has yet to be initiated” (Gallaher 2022). In short, neither eastern nor western Christian theologians are likely to accept transhumanist technology as a means for the ultimate transformation, sanctification or theosis.

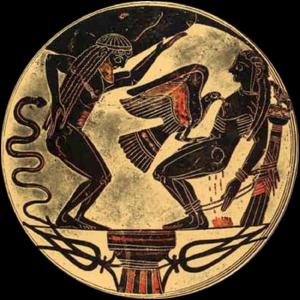

The Promethean Syndrome

A Promethean mood or ambiance imbues the Transhumanist Manifesto. Now, is there more than one manifesto? Regardless, Simon Young’s manifesto is decidedly Promethean. Young recommends that transhumanists play God. This results in a question: just who is God anyway?

A Promethean mood or ambiance imbues the Transhumanist Manifesto. Now, is there more than one manifesto? Regardless, Simon Young’s manifesto is decidedly Promethean. Young recommends that transhumanists play God. This results in a question: just who is God anyway?

The hubris of the mythical Prometheus replaces the Olympian gods with human self-confidence, pride, and overreach. “Theists say, ‘Man should not play God’, complains Simon Young. “But the quest to cure disease, enhance abilities, and extend life cannot seriously be called playing—more like replacing a God who is clearly either absent without leave or completely uninterested in reducing human suffering. Let us have no irrational fears about ‘playing God’” (Young 2006, 49). Young is fearless. Science and technology replace God. “From Prometheus to Frankenstein, the myth of punishment for challenge to the Gods derives always from the same cause: the stoical acceptance of human limitations deemed impossible to overcome—and the cowardly fear of the unknown…..Let us reject irrational hubraphobia and seek to improve our minds and bodies in any way we can” (Young 2006, 50) (Peters, Homo Deus or Frankenstein’s Monster? Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics 2022d).

Rejected here by secular H+ is divine grace. Rejected here is a worldview that places the God of salvation at the center. Rejected here is human humility. The transhumanist worldview replaces God with human intelligence and the progress of technology. It would be difficult, I think, to combine this Promethean self-understanding driving transhumanism with any religious vision that requires human humility before a holy God (Peters, Artificial Intelligence, Transhumanism, and Rival Salvations 2019).

For the public theologian, what is at stake is theological anthropology as well as soteriology. What do we mean with terms such as “transhuman,” “posthuman,” or “truly human”? In the New Testament, the risen Jesus Christ is the eikon tou Theou, the imago Dei, the truly human. Will the technological enhancements advocated by transhumanists help get us there?

Conclusion

So we ask: is the term, “Religious Transhumanism,” a mistake? No, of course not. Is the term, “Christian Transhumanism” or CT+ a mistake? No, of course not despite the debate that rages. Even so, sorting through the relationship between adjectives and nouns provides an opportunity for sorting through the issues. What are the issues again?

Secular and atheistic techies own the cultural patent on transhumanism. Adding an adjective such as “religious” or “Christian” only confuses the matter. The original H+ anthropology and soteriology are inescapably Pelagian: we humans by our own power will replace divine grace with Promethean can-do-ism and provide via science the salvation that religion promised but failed to deliver. There is no way to Christianize such a worldview or ethic.

What is reasonable, however, is to augment a religious vision of human transformation with H+ plans for technological transformation. As regular readers of this newsletter have seen, I genuinely appreciate my transhumanist friends and admire their zeal and creativity. The public theologian should offer a critique of H+, to be sure. But, not categorical rejection. To the extent that technological enhancement through AI or IA are able to provide human persons with opportunities for better health, longevity, wellbeing, and flourishing, we should be grateful to H+ technology.

▓

Ted Peters directs traffic at the intersection of science, religion, and ethics. Peters is an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union, where he co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. He authored Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom? (Routledge, 2nd ed., 2002) as well as Science, Theology, and Ethics (Ashgate 2003). He is editor of AI and IA: Utopia or Extinction? (ATF 2019). Along with Arvin Gouw and Brian Patrick Green, he co-edited the new book, Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics hot off the press (Roman and Littlefield/Lexington, 2022). Soon he will publish The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters directs traffic at the intersection of science, religion, and ethics. Peters is an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union, where he co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. He authored Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom? (Routledge, 2nd ed., 2002) as well as Science, Theology, and Ethics (Ashgate 2003). He is editor of AI and IA: Utopia or Extinction? (ATF 2019). Along with Arvin Gouw and Brian Patrick Green, he co-edited the new book, Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics hot off the press (Roman and Littlefield/Lexington, 2022). Soon he will publish The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

This fictional spy thriller, Cyrus Twelve, follows the twists and turns of a transhumanist plot.

▓

References

Braxton, Donald. 2021. “Religion Promises but Science Delivers.” The Fourth R: Westar Institute 34:3 3-9.

Gallaher, Brandon. 2022. “Technological Theosis? An Eastern Orthdodox Critique of Religious Transhumanism.” In Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics, by Brian Patrick Green, and Ted Peters, eds Arvin Gouw, 161-182. Lanham MA: Lexington.

Jenson, Robert W. 2002. “The Great Transformation.” In The Last Things: Biblical and Theological Perspectives on Eschatology, by eds Carl E Braaten and Robert W Jenson, 33-43. Grand Rapids MI: Wm B Eerdmans.

Markham, Ian. 2020. “Public Theology: Toward a Christian Definition.” Anglican Theological Review 102:2 179-192.

Peters, Ted. 2019. “Artificial Intelligence, Transhumanism, and Rival Salvations.” Covalence https://luthscitech.org/artificial-intelligence-transhumanism-and-rival-salvations/.

Peters, Ted. 2019. “Boarding the Transhumanist Train: How Far Should the Christian Ride?” In The Transhumanist Handbook, by ed. Newton Lee, 795-804. Switzerland: Springer.

Peters, Ted. 2022d. “Homo Deus or Frankenstein’s Monster? Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics.” In Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics, by Brian Patrick Green, and Ted Peters, eds Arvin M Gouw, 3-30. Lanham MA: Lexington.

Peters, Ted. 2022a. Is AI a Shortcut to Virtue? to Holiness? Column, https://www.patheos.com/blogs/publictheology/2021/11/ai-ethics-a-shortcut-to-sanctification/: Patheos Public Theology.

Peters, Ted. 2022c. Radical Life Extension? Cybernetic Immortality? Or, Resurrection of the Body? Column, https://www.patheos.com/blogs/publictheology/2022/01/h-3-radical-life-extension-cybernetic-immortality-or-resurrection-of-the-body/: Patheos Public Theology.

Peters, Ted. 2005. “Techno-Secularism, Religion, and the Created Co-Creator.” Zygon 40:4: 845-862.

Peters, Ted. 2019. “The Ebullient Transhumanist and the Sober Theologian.” Sciencia et Fides 7:2 97-117.

Peters, Ted. 2011. “Transhumanism and the Post-Human Future: Will Technological Progress Get Us There?” In H+ Transhumanism and Its Critics, by eds William Grassie and Gregory Hansell, 147-175. Philadelphia: Metanexus Institute.

Redding, Micah. 2022. “Why Christian Transhumanism?” In Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics, by Brian Patrick Green, and Ted Peters, eds Arvin M Gouw, 113-128. Lanham MA: Lexington.

Vita-More, Natasha. 2018. Transhumanism: What is it? New York: Self Published.

Young, Simon. 2006. Designer Evolution: A Transhumanist Manifesto. Amherst NY: Prometheus Books.