Easter’s Cosmic Meaning

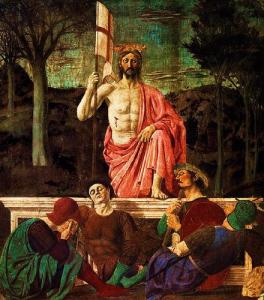

Rising from the grave is not merely a nice thing that happened to the dead Jesus. There’s so much more. Jesus’ Easter resurrection has cosmic meaning. Easter’s cosmic meaning is this: just as Jesus died, so also will this cosmos come to an end. Further, just as Jesus rose from the dead, this cosmos will enjoy a renewal, a transformation, a new creation. Easter is yesterday’s microcosm of tomorrow’s macrocosm. [Art by Pierra della Francesco]

Rising from the grave is not merely a nice thing that happened to the dead Jesus. There’s so much more. Jesus’ Easter resurrection has cosmic meaning. Easter’s cosmic meaning is this: just as Jesus died, so also will this cosmos come to an end. Further, just as Jesus rose from the dead, this cosmos will enjoy a renewal, a transformation, a new creation. Easter is yesterday’s microcosm of tomorrow’s macrocosm. [Art by Pierra della Francesco]

Nah! The real meaning of Easter is that eggs hatch new chickens. Right? Or, a mommy and daddy rabbit make lots of bunnies. Right? Or, I can wear my prettiest bonnet in the 5th Avenue Parade. Right?

Or, what do you think about Valparaiso’s Gilbert Meilaender? “The risen Jesus becomes the promise–a kind of down payment–that the new creation will come in God’s good time” (Meilaender 2013, 53) (Peters, The Future of Resurrection 2006).

Easter’s Cosmic Meaning as Prolepsis

Well, let’s try this meaning on for size: Jesus’ Easter resurrection is a prolepsis of the New Creation. With that word, prolepsis, I mean that Easter anticipates the future of the world. Easter pre-incarnates, so to speak, the future renewal of all things. Just as Jesus was raised by God on the first Easter, so God will rescue this estranged creation by transforming it into a New Creation. “The proleptic character of the Christ event, [signifies that] the resurrection of Jesus is indeed infallibly the dawning of the end of history,” writes the late Munich theologian, Wolfhart Pannenberg. Therefore, “the resurrection of the dead, which already happened to Jesus, is still outstanding” for us (Pannenberg, Basic Questions in Theology, 2 Volumes 1970-1971, 2:24).[i]

![]() The God who is creating this world is not done yet. This world will not be fully created until it’s redeemed. The resurrection of Jesus Christ in his person anticipates the renewal of all things yet to come. So, Easter’s cosmic meaning is that Easter is a promise, God’s oath, a down payment on universal transformation. “Salvation means the transformation and redemption of the entire human family, and the entire cosmos that we call home,” proclaims systematic theologian Kristin Johnston Largen (Largen 2021, 192) [In this icon notice how the Easter Christ is reaching down and pulling Adam and Eve–that’s you and me–out of their graves with him].[ii]

The God who is creating this world is not done yet. This world will not be fully created until it’s redeemed. The resurrection of Jesus Christ in his person anticipates the renewal of all things yet to come. So, Easter’s cosmic meaning is that Easter is a promise, God’s oath, a down payment on universal transformation. “Salvation means the transformation and redemption of the entire human family, and the entire cosmos that we call home,” proclaims systematic theologian Kristin Johnston Largen (Largen 2021, 192) [In this icon notice how the Easter Christ is reaching down and pulling Adam and Eve–that’s you and me–out of their graves with him].[ii]

Perhaps New Testament historian N.T. Wright best sums up the point of this Patheos column post. “The central Christian affirmation is that what the creator God has done in Jesus Christ, and supremely in his resurrection, is what he intends to do for the whole world–meaning by ‘world’ the entire cosmos with all its history” (N. Wright 2007, 16-17).[iii]

Prove it!

My atheist friends like to shout repeatedly: “prove it!” The New Atheists accuse Christians of believing fairy tales and living in a superstitious worldview. Scientific materialism is provable, say today’s evangelical atheists. But, they also say that religious claims are not. Are the new atheists right on this? No, this is not quite accurate, especially when it comes to Easter’s cosmic meaning.

To be clear, a proof for Jesus’ Easter resurrection is unlike the kind of proof we know in empirical science. Easter is not amenable to repeated experiment. Rather, as a historical event, the Bible’s resurrection accounts are subject to evaluation of evidence and probabilities based on that evidence.

What counts as evidence? Two things: the empty tomb and the appearances of the risen Jesus Christ to as many as five hundred people.[iv] We have documents that provide testimony by witnesses. This is the kind of evidence that counts when making historical judgments.

What counts as evidence? Two things: the empty tomb and the appearances of the risen Jesus Christ to as many as five hundred people.[iv] We have documents that provide testimony by witnesses. This is the kind of evidence that counts when making historical judgments.

If the historian assumes that dead people never rise, then the historian may not give the evidence a fair evaluation. This assumption about nature—dead people stay dead—is imported from naturalism. It’s a metaphysical assumption. It’s not a historical conclusion. If treated dogmatically, this naturalistic assumption might blind the historical researcher to evidence that at least one person rose from the dead.

Historical Explanation

Historians who turn over every rock multiple times largely conclude that, most probably, the claim that Jesus rose from the dead is true. Why? Because, among the alternative explanations, this is the most adequate explanation for why early followers of Jesus came to believe that this is true.[v] A more probable explanation is the best one can get from any similar historical study. In sum, the claim that Jesus rose from the dead has the highest probability of being true.

You’ll find this argument among historians and theologians such as Wolfhart Pannenberg (Pannenberg 1977), Gerald O’Collins, S.J. (O’Collins 2012), N.T. Wright (Wright 2003), and Gary Habermas (Habermas, Risen Indeed: A Historical Investigation into the Resurrection of Jesus 2021) (D’Souza 2009).

History provides the data which the systematic theologian interprets. This leads to knowledge. Philosophical theologian Nancey Murphy and mathematical cosmologist George Ellis are confident: “Theology constitutes knowledge in exactly the same sense of the term as does science” (Murphy 1996, 7). Even though the data may be historical, the systematic theologian reasons much like the scientist in the view of DoSER at AAAS, Oxford’s Faraday Institute, the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences or CTNS, Biologos, the Institute for Religion in an Age of Science or IRAS, Europe’s ESSSAT, Australia’s ISCAST, the Clergy Letter Project, and others engaged in the dialogue between science and faith.

What about those laws of nature?

Suppose the fundamental category for explaining reality is history. Things change, after all. We observe this. So, do the laws of nature change too?

What?! But the laws of nature seem to be eternal. Right?

Oh, yes, the laws of nature formulated by our scientists appear to be eternal. But, to say the laws of nature are eternal would be to make a metaphysical judgment, not a scientific one.

Famed physicist Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, invoking the second law of thermodynamics which makes clear that time in our universe goes only one direction—from the past to the future—,concluded that nature is fundamentally and irrevocably historical (Weizsäcker 1940, 8). Nature has a story, just as we do. Nature has events, just as we do. The theologian, then, must affirm that what the scientist formulates as the laws of nature expresses the faithfulness of God within the ongoing history of creation (Pannenberg, Basic Questions in Theology, 2 Volumes 1970-1971, 2:76n).

This calls to mind Saint Symeon (949-1022), who was called a “New Theologian” a thousand years ago. Symeon put it this way: “The words and decrees of God become the law of nature” (Symeon 1979, 82). Should God wish to change a law of nature, then God is free to do so. And this is exactly what God did on the first Easter Sunday.

The First Instantiation of a New Law of Nature (FINLON)

Jesus’ Easter resurrection is the First Instantiation of a New Law of Nature (FINLON), declares Robert John Russell, founder and director of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences in Berkeley, California. The eschatological new creation will include some new laws. Here’s one new law: dead people rise. Easter’s cosmic meaning is that one of those future new laws has obtained here and now, within the old creation. “By analogy with the resurrection, the new creation will be a transformation of the world as a whole and all that is in it. Thus, the new creation will be both continuous and discontinuous with the present world” (Russell, Bodily Resurrection, Eschatology, and Scientific Cosmology 2002, 9). [Art by Peter Paul Rubens].

Jesus’ Easter resurrection is the First Instantiation of a New Law of Nature (FINLON), declares Robert John Russell, founder and director of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences in Berkeley, California. The eschatological new creation will include some new laws. Here’s one new law: dead people rise. Easter’s cosmic meaning is that one of those future new laws has obtained here and now, within the old creation. “By analogy with the resurrection, the new creation will be a transformation of the world as a whole and all that is in it. Thus, the new creation will be both continuous and discontinuous with the present world” (Russell, Bodily Resurrection, Eschatology, and Scientific Cosmology 2002, 9). [Art by Peter Paul Rubens].

To deny that the laws of nature can change would risk locking us into a static world of deterministic physics. It might deny the historicity of natural events which we can observe. So, Arthur Peacocke, a biologist and theologian, asks for a new ontology to account for both Jesus’ Easter resurrection and God’s promise of a new creation. “In Jesus the Christ a new reality has emerged and a new ontology is inaugurated….This incarnation uniquely exemplifies that emergence-from-continuity that characterizes the entire process whereby God is informing the world and continuously creating through discontinuity” (Peacocke 2007, 37). Discontinuity amidst continuity makes novelty possible. To have either Easter or new creation requires an ontology that includes novelty.

Conclusion

“The future has already begun,” announces the indefatigable Tübingen theologian, Jürgen Moltmann. Here is Easter’s cosmic meaning as we experience it daily.

“The conflict between the rising sun and the departing shadows of the night is already being fought out. There is already a struggle for justice against injustice, and a protest of the forces of life against the forces of death. This conflict is experienced in every Christian existence as a conflict between a life ensouled by God’s Spirit of life and a life which, faint-hearted and apathetic, bears the marks of the sickness unto death. Paul calls the first life ‘spirit’, and the second ‘flesh'” (Moltmann 1997, 72).

We have been asking about Easter’s Cosmic Meaning. God’s plan to finish creation by redeeming creation is anticipated proleptically in Jesus’ Easter resurrection. As God raised Jesus, so also will God raise you and me. As God raised Jesus to eternal life, so also will God renew and eternalize, so to speak, the redeemed creation. All of creation. Now, that’s a lot of meaning.

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. He is author of Short Prayers and The Cosmic Self. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. He is author of Short Prayers and The Cosmic Self. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters’ fictional series of espionage thrillers features Leona Foxx, a hybrid woman who is both a spy and a parish pastor.

▓

References

Bauckham, Richard. 2010. The Bible and Ecology. Waco TX: Baylor University Press.

D’Souza, Dinesh. 2009. Life Beyond Death: The Evidence. Washington DC: Regnery.

Habermas, Gary. 2021. Risen Indeed: A Historical Investigation into the Resurrection of Jesus. Ann Arbor MI: Lexham.

—. 2004. The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus. Grand Rapids MI: Kregel Publications.

Largen, Kristin. 2021. “Plurality and Salvation: Possibilities in Pannenberg’s Soteriology for Comparative Theology.” In The Enduring Promise of Wolfhart Pannenberg, by ed Andrew Hollingsworth, 183-200. Lanham MA: Lexington.

Meilaender, Bilbert. 2013. Should We Live Forever? The Ethical Ambiguities of Aging. Grand Rapids MI: Wm B Eerdmans.

Moltmann, Jürgen. 1997. The Source of Life: The Holy Spirit and the Theology of Life. Minneapolis: Fortress.

Murphy, Nancey, and George Ellis. 1996. On the Moral Nature of the Universe: Theology, Cosmology, and Ethics. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

O’Collins, Gerald. 2012. Believing in the Resurrection. New York: Paulist.

Pannenberg, Wolfhart. 1970-1971. Basic Questions in Theology, 2 Volumes. Minneapolis: Fortress.

—. 1977. Jesus–God and Man. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox.

Peacocke, Arthur. 2007. All That Is: A Naturalistic Faith for the Twenty-First Century. Minneapolis: Fortress.

Peters, Ted. 2015. God–The World’s Future: Systematic Theology for a New Era. 3rd. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Peters, Ted. 2006. “The Future of Resurrection.” In The Resurrection: John Dominic Crossan and N.T. Wright in Dialogue, by ed Robert Steward, 149-170. Minneapolis: Fortress.

Polkinghorne, John. 1994. The Faith of a Phsicist / Gifford Lectures . Princeton NJ: Princeton Universit Press ISBN 0-691-03620-9.

Russell, Robert John. 2002. “Bodily Resurrection, Eschatology, and Scientific Cosmology.” In Resurrection: Theological and Scientific Assessments, by Robert John Russell, and Michael Welker, eds Ted Peters, 3-30. Grand Rapids MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans.

—. 2012. Time in Eternity: Pannenberg, Physics, and Eschatology in Creative Mutual Interaction. Notre Dame IN: University of Notre Dame Press ISBN 13: 978-0-268-04059-8.

Sonderegger, Katherine. 2020. Systematic Theology Volume 2. Minneapolis: Fortress.

Suchocki, Marjorie. 1994. The Fall to Violence: Original Sin and Relational Theology. New York: Continuum.

Symeon, New Theologian. 1979. The First Created Man. Platina CA: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood.

Weizsäcker, Carl Friedrich von. 1940. The History of Nature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wright, N T. 2003. Resurrection of the Son of God. Minneapolis: Fortress.

Wright, NT. 2007. “Cosmic Future: Progress or Despair?” In From Resurrection to Return: Perspectives from Theology and Science on Christian Eschatology, by Christine Ledger, and Stephen Picard, eds James Haire, 5-31. Adelaide: ATF Press.

Endnotes

[i] “The proleptic character of the destiny of Jesus is the basis for the openness of the future for us….the openness of the future belongs constitutionally to our reality” (Pannenberg, Basic Questions in Theology, 2 Volumes 1970-1971, 2:25).

[ii] Process theologian Marjorie Hewitt Suchocki draws out the cosmic implications of our daily interrelatedness. “We are interwoven. In this interwovenness, interdependence combine with the urge toward well-being equals responsibility for the well-being of self and others…our responsibility finally draws into connection with the entire universe” (Suchocki 1994, 71).

[iii] In addition, a leading scholar in the field of physics and theology, John Polkinghorne, catches Easters’ cosmic meaning. “The resurrection of Jesus is the vindication of the hopes of humanity….The resurrection of Jesus is a great act of God, but its singularity is its timing, not its nature, for it is a historical anticipation of the eschatological destiny of the whole of humankind” (Polkinghorne 1994, 121).

[iv] “The combination of empty tomb and appearances of the living Jesus forms a set of circumstances which is itself both necessary and sufficient for the rise of early Christian belief. Without these phenomena, we cannot explain why this belief came into existence, and took the shape it did. With them, we can explain it exactly and precisely” (N. T. Wright 2003, 696, Wright’s italics.).

[v] “The evidence is thus strong that this [Jesus’ Easter resurrection] was a genuine experience within the consciousness of these [New Testament] witnesses….[Resurrection is] referring to a new kind of reality hitherto unknown because not hitherto experienced. Resurrection manifests a new kind of ontology in the nature of the risen Jesus” (Peacocke 2007, 34).