The Public Theologian as Ecumenical & Ecumenic Pluralist

The Public Theologian as Ecumenical & Ecumenic Pluralist

PT 1002

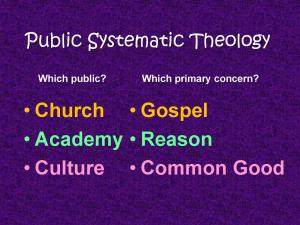

What is public theology? Among other agendas, the public theologian takes up both ecumenical and ecumenic matters.

Ecumenical theology today? The public theologian turns inward toward the church and outward toward the world beyond the church. Public theology, says Karen O’Donnell, “is focused on justice, it centres itself around kindness, it is humble…and is undertaken alongside God.” Of the many renderings of public theology, I insist that it consists of theology conceived in the church, critically reasoned in the academy, and offered to the wider culture for the sake of the global common good.

Here is my point in this column post: the public theologian should affirm both the ecumenical and the ecumenic. To be “ecumenical” means to embrace the full Body of Christ throughout the world. To be “ecumenic” means to embrace that very world as a whole (the ecumené). The ecumenic pluralist folds plurality–even the plurality of religions along with the plurality of race, ethnicity, class, gender, and age–into an integrated wholeness.

Here is the problem I’d like to address in this post: empowering the local community requires equal commitment to the common good. Current postcolonial theologies of liberation direct their efforts at empowering the subaltern. Ranajit Guha tells us subaltern means “of inferior rank.” Guha along with Gayatry Chakravorty Spivak is concerned about identity and self-control “expressed in terms of class, caste, age, gender, and office or in any other way” (Guha 1988). The postcolonial liberation theologian’s concern for subaltern peoples constitutes an authentic expression of Jesus’ love for the disenfranchised and the theologian’s preferential option for the poor. Yet, a problem arises in worldview construction. What’s missing is a vision of the ecumené–the whole world–and the common good of that whole world. If simultaneous empowerment of a plurality of subaltern groups is the theologian’s exclusive agenda, then this promotes only a form of anarchy. Success at empowerment could only lead to a society of competing power centers. For worldview construction, this pluralistic approach needs placement within a more comprehensive vision, namely, a vision of the global ecumené replete with the common good.

In this Patheos series, I have been describing public theology as conceived in the church, critically reasoned in the academy, and meshed with the culture for the sake of the global common good. These two principles—the ecumenical and the ecumenic principles—ask the public theologian to take a leap of faith into the unseen. I ask the public theologian to trust in both the unity of the Body of Christ and the unity of the human race even when only plurality seems visible.

In this Patheos series, I have been describing public theology as conceived in the church, critically reasoned in the academy, and meshed with the culture for the sake of the global common good. These two principles—the ecumenical and the ecumenic principles—ask the public theologian to take a leap of faith into the unseen. I ask the public theologian to trust in both the unity of the Body of Christ and the unity of the human race even when only plurality seems visible.

Public theology is not merely Church Dogmatics, wherein systematic theology provides the church with faith seeking understanding (fides quaerens intellectum). Rather, conceived in the church and critically filtered through the academy, public theology addresses the world for the sake of the common good. According to Otago public theologian David John Bromell, “Public theology is a form of applied theology. It reflects critically on the ethical and political implications, here and now, of claims expressed or implied in religious faith and witness, and does so in the public sphere, in publicly accessible ways.”

Just what is public theology again? In this Patheos series we’ve asked public theologians such as Katie Day, Kang Phee Seng, Rudolf von Sinner, Valerie Miles-Tribble, Robert Benne, Binoy Jacob, and others around the world. These voices have been raised tacitly on behalf of both the subaltern and the ecumené’s common good. What we need to do here is add some specificity regarding what we mean by the ecumenical and the ecumenic.

Like a house builder, Clive Pearson, editor of the International Journal of Public Theology, starts with a foundation. “The need for a theoretical basis of a public theology is always ever-present.” The following discussion of ecumenical and ecumenic theology helps to lay this theoretical foundation.

The Ecumenical Principle

Even if the public theologian relies on the method and system of a specific tradition–such as the Wesleyan Quadrilateral, the Orthodox appeal to the councils and patristics, the Westminster Confession, the Augsburg Confession, Scripture plus canon, or free church—all prescind from the one Bible. The Bible is inescapably the ecumenical principle (Peters 2015, 129-132).

Even if the public theologian relies on the method and system of a specific tradition–such as the Wesleyan Quadrilateral, the Orthodox appeal to the councils and patristics, the Westminster Confession, the Augsburg Confession, Scripture plus canon, or free church—all prescind from the one Bible. The Bible is inescapably the ecumenical principle (Peters 2015, 129-132).

The Bible is the cradle of Christ. In that cradle we rock the gospel. The gospel is the story of Jesus told with its significance. Its significance for those of us in the Christian church is that God has promised new creation, justification, and proclamation. In the church, the public theologian is responsible for the gospel. In the academy, the public theologian is responsible to reason. In the wider culture, the public theologian is responsible to the common good. The Ecumenical Principle has to do with the first public, the church worldwide.

Faithfulness to the scriptural message makes theology ecumenical rather than parochial. All Christians of all times and all places must appeal to the Bible as the criterial source for what they believe. Both progressive Christians as well as fundamentalist leaning evangelical Christians should be able to embrace this ecumenical principle when engaging in public theology. “Public theology…is biblical and theological and then extended into the public sector through political means,” says Sojourners.

This is the fate bequeathed us as a religion founded upon a historical event of revelation. Consequently, no matter what language we speak or cultural customs we adopt there will be certain persistent biblical symbols that will always link us with the communion of saints around the world and across the centuries. By returning constantly to the originary symbols of scripture, the agenda of today’s theologian can transcend the parochial fixations of various denominations and various ethnic traditions within the wider Christian church. The expository function of theology naturally yields this ecumenical principle that leads to dialogue and fellowship.

Ressourcement: Bible and Creed

Here, I take with utmost seriousness George Lindbeck’s call for ressourcement—returning to the Bible as source—to achieve the consensus fidelium that might be able to reconcile the various confessional traditions (Likndbeck 1989, 2:269).

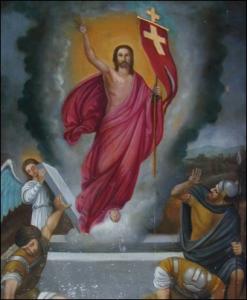

A valuable variant is the first thesis of the Post-Vatican II proposal by Heinrich Fries and Karl Rahner regarding the possibility of attaining church unity in our time. The thesis is this: “The fundamental truths of Christianity, as they are expressed in Holy Scripture, in the Apostles’ Creed, and in that of Nicea and Constantinople are binding on all partner churches of the one Church to be” (Fries 1985, 7). This means that the basic Christian symbols as found in the Bible and shared by virtually all of Christendom up until the fourth century provide fundamental identity for Christians. Whether Scripture Alone (sola scriptura) or Scripture plus Creeds or even Councils, there are historical reasons for affirming Christian unity despite its plurality. (Resurrection painting, Franciscan church, Crete)

A valuable variant is the first thesis of the Post-Vatican II proposal by Heinrich Fries and Karl Rahner regarding the possibility of attaining church unity in our time. The thesis is this: “The fundamental truths of Christianity, as they are expressed in Holy Scripture, in the Apostles’ Creed, and in that of Nicea and Constantinople are binding on all partner churches of the one Church to be” (Fries 1985, 7). This means that the basic Christian symbols as found in the Bible and shared by virtually all of Christendom up until the fourth century provide fundamental identity for Christians. Whether Scripture Alone (sola scriptura) or Scripture plus Creeds or even Councils, there are historical reasons for affirming Christian unity despite its plurality. (Resurrection painting, Franciscan church, Crete)

What comes after the Nicene Creed in history distinguishes one group of Christians from another. After the dispute over Christ’s two natures at the Council of Chalcedon in 451, the Nestorians and Oriental Orthodox (Syriac speaking) churches separated from those of the Chalcedonian confession. After the dispute over filioque and the role of the papacy in the eleventh century, we could distinguish more sharply between the Eastern Orthodox and the Roman or Latin churches. After the Reformation of the sixteenth century, we could distinguish between the Protestants and the Roman Catholics. Subsequent disputes created subsequent sub-identities within the one identity that all Christians share—namely, all Christians understand themselves as trying to explicate the meaning of what God has revealed in Christ and transmitted to us through Scripture.

The Catholic Spirit

The ecumenical principle applies to Christians today as they seek to reemphasize their common identity rooted in the events witnessed to in the Bible and confessed at Nicaea. It is an identity of roots with a plurality of branches. The ecumenical principle is the principle of unity amid our support for plurality. When the theologian returns repeatedly to the originary sources of the faith, he or she or they is tacitly reaffirming the oneness of the faith shared among all those who take the name of Christian.

The ecumenical principle understood in this way is an expression of what Methodist John Wesley refers to as the true “catholic spirit.” By this term, he is not referring to the institution centered in Rome, the Roman Catholic Church. With a lower case c the term “catholic spirit” refers to the universal Christian spirit. It is an affirmation of the one originary gospel amid differing opinions about that gospel.

Discourse Clarification and Worldview Construction

When answering the question–what is public theology?–I frequently aver that public theology is conceived in the church, critically honed in the academy, and meshed with the world for the sake of the world. Thereby, it becomes ecumenical in the church and ecumenic in the world.

The public theologian enters existing public discourse by offering clarity through analysis. Theological anthropology is a particularly ripe resource to draw upon when pointing out the naivete of most ideologies as well as the deceit in most political self-justifications.

Broadening the catholic spirit, the public theologian contributes theological and ethical building materials for the construction of a comprehensive and protean worldview. “World views … have a strongly motivating and inspiring function. A socially shared view of the whole gives a culture a sense of direction, confidence and self-esteem” (Aerts, 8). We each need a worldview to provide the context of meaning for daily life and for inspiring society’s goals. Worldview construction is the ecumenic principle in action.

The Ecumenic Principle

The ecumenical principle differs from the ecumenic principle. Whereas the ecumenical principle draws our attention to the internal unity of the one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church, the ecumenic principle draws our attention to the world outside or beyond the church. Ecumenic consciousness places Christian theological reflection into the context of our secular society, global communications, cultural sensibilities, political movements, natural science, the arts, and the manifold of the world’s religious traditions. (Globe at Berkeley BART Station)

The ecumenical principle differs from the ecumenic principle. Whereas the ecumenical principle draws our attention to the internal unity of the one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church, the ecumenic principle draws our attention to the world outside or beyond the church. Ecumenic consciousness places Christian theological reflection into the context of our secular society, global communications, cultural sensibilities, political movements, natural science, the arts, and the manifold of the world’s religious traditions. (Globe at Berkeley BART Station)

Max L. Stackhouse on Globalization

Princeton pioneer in public theology, Max Stackhouse, forecasted that globalization would be a harbinger of planetization., of wholeness and harmony. First, Stackhouse is descriptive.

Globalization as a dynamic process suggests not only that the whole world can be conceived as “one place,” a single reality, but as a reality involved in a process of change, so that will transcend its present reality. It presumes an “already” and “old” nature, indeed a kosmos and oikoumene, that are necessary and enduring, but incomplete, flawed,

Then, Stackhouse turns prescriptive.

Gobalization, understood in its more complex meanings, could be “for good” — both lasting and for human well-being. It could promote a highly pluralistic global civilization with increased prospect for peace with justice. In the final analysis, however, it is unlikely co happen unless it finds its focus in Christ as Lord, for Christ is the one who has, and can ever and again, renew the covenant between God and humanity, and point souls toward reconciliation with God and neighbor, and societies coward a New Jerusalem.

Stackhouse penned this hopeful forecast in 2003. During the two decades since then, globalization has become balkanization. Natural and societal forces have moved toward disunity rather than unity, toward pluralism rather than cosmopolitanism. So, I along with other public theologians have proposed substituting planetization rather than globalization to lift up the ideal ecumenic principle, the comprehensive common good.

The Threats & Opportunities posed by Plurality and Pluralism

Rife in our planetary society today are both plurality and pluralism. International tensions along with acrimonious rivalries between ideologies keep the world always on the brink of war. The mobile phone screens of teenagers are flooded with incommensurate worldviews, leaving confusion and disorientation if not depression in their wake. Instead of a single planetary society committed to the common good, we are left with a plurality of inconsolable and irreconcilable rivals.

Rife in our planetary society today are both plurality and pluralism. International tensions along with acrimonious rivalries between ideologies keep the world always on the brink of war. The mobile phone screens of teenagers are flooded with incommensurate worldviews, leaving confusion and disorientation if not depression in their wake. Instead of a single planetary society committed to the common good, we are left with a plurality of inconsolable and irreconcilable rivals.

To make matters worse, deconstructionist postmodernists have turned descriptive plurality into prescriptive pluralism. By adding the ‘ism’ to ‘plurality’, the disintegrative perspective becomes itself an ideology. (Marin Art Center). Anxious Patheos evangelicals and progressives turn deconstructionism over and over in their hands like a child with a mud pie.

It is important to note that ideological pluralists among liberation theologians are rightly concerned about justice awarded to marginalized cultures, to the subaltern. The pluralist position is self-contradictory, of course, because justice is a universal—even eternal—standard that includes both the dominant and the dominated. The net result of this contradiction is an ideology that supports fragmentation, confrontation, dissolution and, finally, anarchy. Not the common good.

Human Unity as a Leap of Faith into the Unseen

Over against deconstructionist pluralism, the ecumenic principle affirms human unity, even the unity of the human with nature. The concept of the ecumené appears as early as Homer, referring to the entire world we can perceive this side of the horizon.

What the public theologian needs to affirm as a matter of faith, I believe, is ecumenic pluralism. Despite the plurality we observe, there exists a single human race. By faith, despite the evidence to the contrary, the public theologian affirms a single universal humanum (Voegelin 1956-1987, 4:201-207). The New Testament promise of the eschatological kingdom of God calls us to this faith in the unseen.

Conclusion

How can we integrate the healthy justice agenda pursued by postcolonial liberation theologians with the ecumenic and ecumenical vision of the common good pursued by the public theologian? Via the principle of subsidiarity. Latin American theologian, Pope Francis, defines this principle in Laudato Si.

How can we integrate the healthy justice agenda pursued by postcolonial liberation theologians with the ecumenic and ecumenical vision of the common good pursued by the public theologian? Via the principle of subsidiarity. Latin American theologian, Pope Francis, defines this principle in Laudato Si.

- 196. …the principle of subsidiarity…grants freedom to develop the capabilities present at every level of society, while also demanding a greater sense of responsibility for the common good from those who wield greater power.

That is to say, according to the principle of subsidiarity, the local subaltern group is epistemologically privileged. The local marginalized group knows better than anyone what the problems are that need mitigation. And the oppressed should rightfully initiate the action needed for justice. Yet, the pursuit of local justice contributes to, rather than detracts from, justice on a global scale. The principle of subsidiarity following the guiding light of the common good integrates what is local with the planetary ecumené.

The ecumenical principle and the ecumenic principle are both based upon a vision of the whole. The ecumenical principle affirms the oneness of the Body of Christ throughout the world. The ecumenic principle affirms the oneness of the human race. It also affirms the oneness of humanity with nature. Both the ecumenical and ecumenic principles are affirmed by faith, not by sight.

While from day to day on the surface of our earth we encounter the dividing walls of culture and the barriers of prejudice, we can still imagine the one world seen by the astronauts looking back from the horizon. With this in mind, ecumenic pluralism affirms descriptively the side-by-side existence of various and contradictory perspectives, worldviews, or approaches to human understanding and living. In conjunction it affirms prescriptively that we should act as if all this diversity belongs to a greater whole. Such acting would be founded not upon what can be observed from our day-to-day perspective, nor upon the judgments of academic anthropologists, but rather upon our faith in God’s unifying and fulfilling plan. The vision of one world with one common good is an anticipation of things to come.

Bibliography

Aerts, D., Apostel, L., de Moor, B., Hellemans, S., Maex, E., Van Belle, H., Van der Veken, J., 1994. World Views: From Fragmentation to Integration. Brussels: VUB Press.

Fries, Heinrich and Karl Rahner. 1985. Unity of the Churches. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Gebser, Jean. 1985. The Ever Present Origin. Athens OH: Ohio University Press.

Guha, Ranajit, 1988, Preface: On Some Aspects of the Historiography of Colonial India. Selected Subaltern Studies. Eds., Ranajit Guha and Gayatri Chakrovorty Spivak. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lindbeck, George. 1989. “Ecumenical Theology.” In The Modern Theologians, 2 Volumes, by ed David F Ford. Oxford: Blackwell.

Peters, Ted. 2015. God–The World’s Future: Systematic Theology for a New Era. 3rd. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Voegelin, Eric. 1956-1987. Order and History, 5 Volumes. Baton Rouge LA: Louisiana State University Press.

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his just published new book, The Voice of Public Theology (ATF 2023). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

▓