My wife told me to stay out of this conversation. She said I’d only invite attacks and a bunch of headaches. It’s typically good advice to listen to your wife. But today, I’m going rogue. My email box will judge whether I made a good decision.

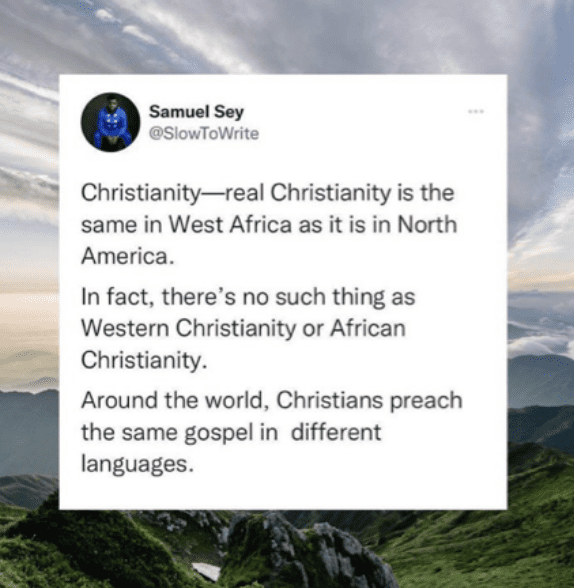

Words matter. They both affect people and reflect their perspectives. There is harm in not paying attention to the context of words. Check out the following quote from Samuel Sey’s recent post.

The inconvenient problem with words is that their meaning always depends on context. The same word can have different connotations depending on the contacts in which it’s said. If we ignore this fact, we open ourselves up to several problems.

The inconvenient problem with words is that their meaning always depends on context. The same word can have different connotations depending on the contacts in which it’s said. If we ignore this fact, we open ourselves up to several problems.

First, we don’t listen to what people actually say. We import our assumptions into their words. Second, we misrepresent people, often even demonizing them for suggesting things they don’t really believe. Third, we perpetuate division, bride, and greater hurt.

How I wish Christians would recognize is a simple point: we compromise the truth when we settle for truth.

What I mean is that we can neglect or misrepresent the truth simply because some aspect of what we say is true. So, we defend ourselves and ignore the criticisms leveled against us. Samuel Sey’s comment above opens the door for such compromise.

When he speaks of “real Christianity,” I think he means the real “gospel.” Such use of “Christianity” is sloppy, especially in the context of an article about deconstruction. Christianity is a general, vague word. It often refers to various sociological expressions of the Christian faith. The faith is expressed in diverse ways across historical, cultural, and geographic contexts.

In that sense, real Christianity is very different in West Africa as it is in North America. And there are such things as Western Christianity and African Christianity.

Deconstructing “Deconstruction”

These remarks matter because of the context in which he makes his comments.

Sey’s article “The First People to Deconstruct Their Faith” is a forthright attack on the phenomenon popularly called “deconstruction.” What he means by this term is unambiguous. For him, deconstruction refers to people rejecting Christ. A few quotes make that clear:

“The first people to deconstruct their faith were people in the Garden of Eden—they were people dissatisfied with God.”

“When people say they’re deconstructing their faith, they’re just using a pretentious phrase to say they’re doubting what God says in the Bible.”

The article plays up the “Did God actually say” language from Genesis 3 to make the connection between deconstructionists and the fall of humanity. It’s a subtle but potent rhetorical move, made more effective by his dropping buzzwords like “Nietzsche” and “postmodernism” to ensure our mental alarms ring at full volume.

What happens, however, if we turn to the New Testament? Jesus’ language intends to elicit doubt. He says, “You’ve heard it said…. But I tell you….” Perhaps, this manner of speaking more accurately captures the sentiments of countless people who undergo deconstruction.

To be sure, many people use “deconstruction” as a synonym for deconversion, referring to their forsaking Jesus. No doubt, the reasons for turning away from Jesus are diverse, sad, and stem from the influence of all sorts of godless ideologies.

However, his and other writers’ blanket dismissal of deconstruction ignores the fact that the word is also used by many people, who rethink and reject much of the church tradition that swallows the biblical gospel, much like Jesus urges in Mark 7:5-9.

My friend and pastor, Joshua Butler, for example, never defines “deconstruction” yet gives 4 reasons why people do it. Ironically, he cites Ivan Mesa, who is more generous and clearer on the matter:

“Deconstruction is the process of systematically dissecting and often rejecting the beliefs you grew up with. Sometimes the Christian will deconstruct all the way to atheism. Some remain there, but others experience a reconstruction. But the type of faith they end up embracing almost never resembles the Christianity they formerly knew.”

This is an accurate definition because it’s necessarily broad. I say “necessarily” because it reflects the actual way people use to term to describe their experience. Butler himself recognizes this point when he says,

“Jesus deconstructs bad teaching in order to reconstruct good teaching. Not all deconstruction is bad.”

Precisely! Yet, contrast this observation with what is implied by Sey’s comments above and Butler’s remark,

“Deconstruction is poison, not medicine. It supplements the sin that’s killing you, rather than healing it. It allows you to save face, to look virtuous in your departure from God (“He’s the problem, not me”), while distracting you from squarely facing your true motivations.”

Do “Deconstructionists” Really Say…?

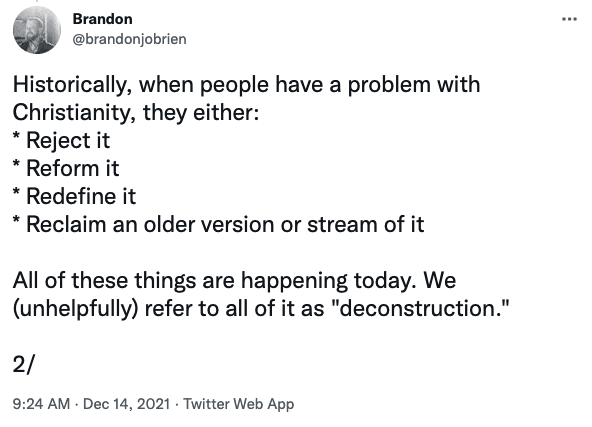

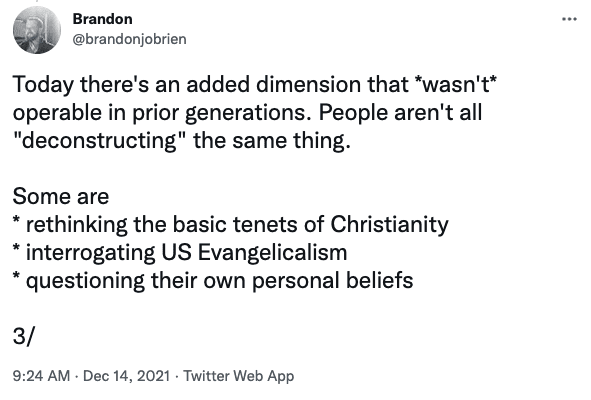

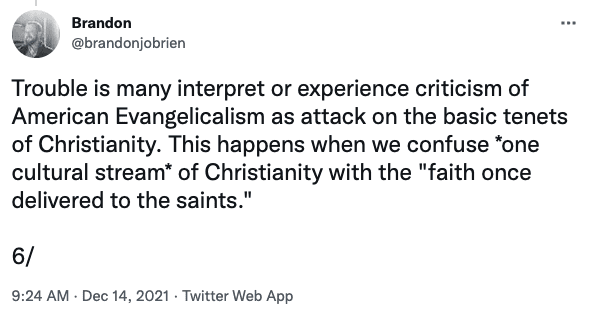

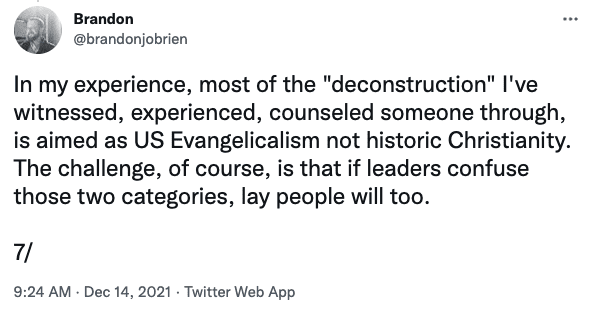

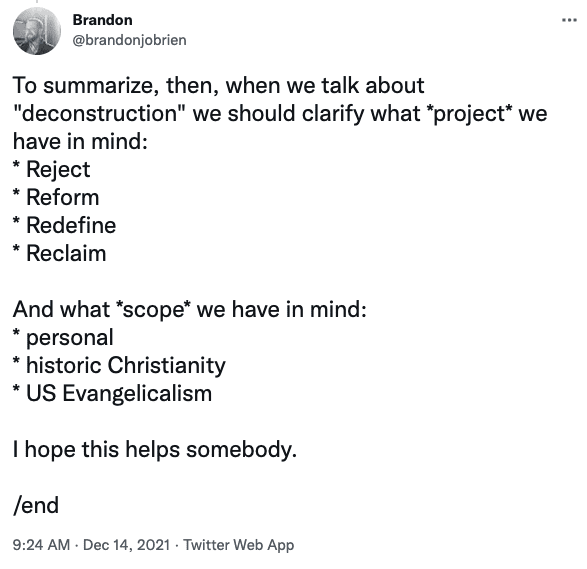

Brandon O’Brien offers a helpful framework for talking about this issue. In a Twitter thread, he says,

Brandon’s summary is spot on.

Three Consequences of Not Defining “Deconstruction”

Why do I raise this discussion?

First, critiques of deconstruction need to define their terms. Better yet, we could begin using other terms that better clarify what’s being described. Loving truth begins with seeking clarity.

Second, if we don’t improve our language, we’ll perpetuate hurt, alienation, and, yes, “deconstruction,” which people say they want to avoid.

Third and perhaps most serious, failing to account for the multiple meanings of deconstruction allows people to ignore the underlying problems that lead to deconstruction.

This is what we find in Sey’s post, who, like Adam and Eve, shifts blame.

He’s aware of what deconstructionists say about their own deconstruction. For example, Sey writes,

“Therefore people who deconstruct their faith believe there is no such thing as Biblical truth, just interpretations—interpretations mostly dominated by supposedly racist, misogynistic, homophobic, and transphobic white people who—according to deconstructionists—preach American or Western Christianity as the only correct interpretation or version of Christianity.”

“This is why deconstructionists tend to call themselves exevangelicals instead of ex-Christians. They believe evangelicalism is Western Christianity—not real Christianity.”

“The Reformers didn’t deconstruct Christianity, they did the opposite. They didn’t reject the authority of the Bible—they returned to the authority of the Bible. People who deconstruct their faith conform to this world.”

In other words, what many people reject is not Jesus but a caricature of Jesus. They don’t necessarily walk away from Christianity but a syncretistic version that reflects certain (sub)cultural values above the Bible.

Sey’s careless language proves reckless. It distracts readers from the substance of deconstructionists’ concerns. We then don’t have to address racism, abuse, misogyny, etc., because, after all, such critics are faithful apostates anyway. Consequently, the church doesn’t have to do the hard work of removing an entire forest of trees from our eyes.

It never occurs to some people that combating these internal problems not only glorifies God but also goes a long way in bringing people to Jesus. Such reform would slow the current wave of deconstruction, which now occurs most frequently among evangelicals. Coincidence?

Sey’s article expresses a genuine desire to protect the church and affirm the gospel. Praise the Lord for that ambition! But it also demonstrates a rhetorical sleight of hand that marks much evangelical discourse.

By fixing our language about “deconstruction,” we might make progress in the task of reconstruction. As Ivan Mesa says:

“Deconstructing, however jarring and emotionally exhausting, need not end in a cul-de-sac of unbelief. In fact, deconstructing can be the road toward reconstructing—building up a more mature, robust faith that grapples honestly with the deepest questions of life.”