The Public Theology of Robert Benne

The Public Theology of Robert Benne

Patheos PT 5007

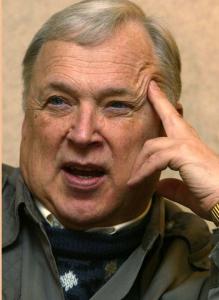

The public theology of Robert Benne provides a reality check. Just what is human nature? How can we forecast the good and the bad in human politics? How can we inspire a lofty vision of the common good while being realistic about what is and is not achievable? When public theologian Robert Benne looks through his paradoxical lenses, he can dispel delusions about both the reality of God and the reality of human nature. (Photo: Robert Benne)

The chief characteristic of public theology is that it is aimed not only at the church but also to the public beyond the church. “Christian witness in secular democratic society means promoting the common good by witnessing to core values rather than seeking privilege for the Christian religion,” says South Africa’s anti-apartheid sockdoliger John DeGruchy. My formulation is similar: public theology is conceived in the church, critically reflected on in the academy, and meshed with the world for the sake of the world. This brand of public theology avoids wasting time trying to justify the place of religion in secular or post-secular society. In Robert Benne’s case, might the paradoxical vision of God’s presence in the cross provide illumination for the wider public beyond the church?

If you want more resources on Public Theology, click here.

This series of today’s leading public theologians includes treatments of Kang Phee Seng, Katie Day, Mwaambi Gideon Mbûûi, Noreen Herzfeld, Paul Chung, and others. I try to avoid those whiney critics who send us on a detour to complain about Christian exclusivity instead of proceeding directly toward the common good. Rather, it is my view that Christian theology has a treasure box of wisdom about human nature that, when shared with the secular public, opens eyes to see and ears to hear. Robert Benne is an opener, so to speak. Put on your thinking cap and read on.

Who is Robert Benne?

Robert Benne is Jordan-Trexler Professor of Religion Emeritus and Research Associate in the Religion and Philosophy Department of Roanoke College in Salem, Virginia. He is currently Professor of Christian Ethics for the online Lutheran Institute of Theology based in Brookings, SD. In 1982 he founded the Roanoke College Center for Religion and Society, which the College named in his honor in 2012. He was Jordan-Trexler Professor of Religion and Chair of the Religion and Philosophy Department at Roanoke College for 18 years. Before that he was Professor of Church and Society at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago for 17 years. A native of Nebraska and a graduate of Midland University, his graduate degrees are from the University of Chicago. He has lectured and written widely on the relation of Christianity and culture. Two of his fourteen books are relevant to the discussion below: The Paradoxical Vision: A Public Theology for the Twenty-first Century (Fortress Press, 1995) and Good and Bad Ways to Think about Religion and Politics (Eerdmans, 2010) (Photo: Grandpa Bob and Max on the track)

Robert Benne is Jordan-Trexler Professor of Religion Emeritus and Research Associate in the Religion and Philosophy Department of Roanoke College in Salem, Virginia. He is currently Professor of Christian Ethics for the online Lutheran Institute of Theology based in Brookings, SD. In 1982 he founded the Roanoke College Center for Religion and Society, which the College named in his honor in 2012. He was Jordan-Trexler Professor of Religion and Chair of the Religion and Philosophy Department at Roanoke College for 18 years. Before that he was Professor of Church and Society at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago for 17 years. A native of Nebraska and a graduate of Midland University, his graduate degrees are from the University of Chicago. He has lectured and written widely on the relation of Christianity and culture. Two of his fourteen books are relevant to the discussion below: The Paradoxical Vision: A Public Theology for the Twenty-first Century (Fortress Press, 1995) and Good and Bad Ways to Think about Religion and Politics (Eerdmans, 2010) (Photo: Grandpa Bob and Max on the track)

He and his wife, Joanna, have been married sixty-two years. They have four children and eight grandchildren.

First Question: What do you mean by “the paradoxical vision”? What are its theological roots and practical applications?

What I meant in the book was the theological vision embedded in the best of the Lutheran tradition that articulates a particular way that organized Christian bodies ought to relate to the public world, particularly politics. It has its roots in many thinkers in the Christian tradition..Augustine to mention one…but was aptly developed in the thought of Martin Luther and the theology of the Lutheran Confessions. It was systematized and transmitted then by many European and American Lutheran writers. And it has been practiced by some major figures—especially Reinhold Niebuhr—who would not identify themselves as Lutherans. I consider Reinhold Niebuhr the best practitioner of the Lutheran vision in recent history. And, of course, Niebuhr made practical applications of that vision better than any theological ethicist, including those among the Lutherans.

One of the reasons I wrote the book was that Lutherans generally did not take up the question of religion’s relating to politics in a concrete way in America. They took positions on specific issues or they, like a couple of my mentors—George Forell and William Lazareth—remained too abstract.

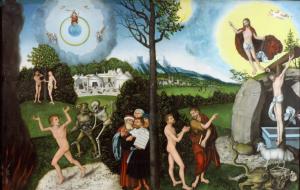

When, in the early 1990s, Mark Noll called for a Lutheran “take” on religion and politics that would challenge the dominant Reformed approach, I took up the challenge. Noll argued that the Reformed have a strong, perhaps perfectionist, doctrine of sanctification, which they then apply to society. Thus, we have the attempt at building the Kingdom of God in America, which H. Richard Niebuhr thought was the way that American Protestants had conceived of their role in America. Theirs was “Christ transforming culture.” (Lucas Cranach, “Law and Gospel”)

Reformation Lutherans, if they are loyal to the “two ways that God reigns—law and gospel” theological approach, can never speak of building the Kingdom of God on earth. [1] Humans can indeed improve conditions on earth as they work with God’s pressure toward justice in his Law, but the sinful propensities of humankind, especially in large organizations, prevent any such realization. Political efforts to reach such a glorified state mostly lead to religionized politics and a miserable state of affairs. We have seen two such catastrophes in the 20th century: the Communist Revolution and the Nazi Third Reich. Both were secularized attempts to build the Kingdom of God on earth.

Reformation Lutherans, if they are loyal to the “two ways that God reigns—law and gospel” theological approach, can never speak of building the Kingdom of God on earth. [1] Humans can indeed improve conditions on earth as they work with God’s pressure toward justice in his Law, but the sinful propensities of humankind, especially in large organizations, prevent any such realization. Political efforts to reach such a glorified state mostly lead to religionized politics and a miserable state of affairs. We have seen two such catastrophes in the 20th century: the Communist Revolution and the Nazi Third Reich. Both were secularized attempts to build the Kingdom of God on earth.

Because of sin, the public theologian can predict historical regression

Indeed, those sinful propensities can bring regress in history too, as we have seen, sadly in the Lutheran homeland itself in the Nazi period.

However, I also believed that the Lutheran tradition was too pessimistic in its view of the role of God’s Law in human history. True, the Law is a “dike to sin,” but it is also a spur to seeking and achieving higher levels of justice. Reinhold Niebuhr saw this, of course, in his application of the Law.

God reigns in two ways

A very important insight of the “two ways that God reigns” is Luther’s insistence that salvation comes through the work of God’s right hand, the Gospel of Jesus of Christ. In this realm—we could visualize it as the “vertical” dimension in which each of us start directly before God—we can do nothing to save ourselves. As Luther wrote: “Before God we are indeed beggars.” It is only the gift of grace in Christ that can do that. So the Lutheran scheme locates salvation as a work of God in Christ, never anything we can do personally or politically.

But we are all given earthly vocations—marriage and family, citizenship, work, church membership—in which the love bestowed upon us in Christ is worked into our callings in the left hand—or horizontal—dimension. We become part of God’s care for his creation in the left-hand kingdom. Thus, there is a distinction but not a separation of the two kingdoms.

Second Question: It’s been a quarter century since you published your threshold crossing book, The Paradoxical Vision: A Public Theology for the Twenty-First Century. Have you had a change of mind on anything? What do you still hold and what would you add or subtract to this book?

Oddly enough, I would change the title. I don’t think the Lutheran vision of religion and politics is paradoxical. [2] I took that language from Richard Niebuhr’s Christ and Culture but I don’t think he thought it was paradoxical, which means that there are two truths that seem contradictory but really aren’t…together they make a profound truth. I believe the Christian gospel is indeed paradoxical: how could the death of a Jewish rabbi of an obscure people at a particular time bring about the possible salvation of all humans who ever lived?

Oddly enough, I would change the title. I don’t think the Lutheran vision of religion and politics is paradoxical. [2] I took that language from Richard Niebuhr’s Christ and Culture but I don’t think he thought it was paradoxical, which means that there are two truths that seem contradictory but really aren’t…together they make a profound truth. I believe the Christian gospel is indeed paradoxical: how could the death of a Jewish rabbi of an obscure people at a particular time bring about the possible salvation of all humans who ever lived?

The Lutheran “take” on religion and politics is coherent in normal terms. An editor who asked me to write about this vision in a national magazine came up with a far better title: One King, Two Kingdoms. I would try that as a new title. It grasps the meaning that I outlined above.

Third Question: Today’s cultural and political context differs from 25 years ago. Specifically, many are worried that American culture is disintegrating. The center cannot hold. Among other ramifications, this may so weaken America that it could become vulnerable to external threats. How do you approach this when looking through the paradoxical vision?

When I looked over the book I was surprised at how much work I had done, and was pretty pleased with it! Whew, it was a lot of work. Of course, if I wrote it again I would have to change the early sections where I try to assess the current situation. Much has changed since the early 1990s when I wrote the book. The USA is far more polarized than it was in the 90s and a good deal of that polarization has both religious sources and implications. We are not only polarized, but fractured in many serious ways. We are further into a “post-Christian” America than I discerned in the 90s. The secular progressives, who are increasingly in charge of the “heights of the culture,” are more and more hostile toward classic Christianity. Christianity itself is fracturing into progressive and orthodox camps, both declining in public influence.

I thought I got the beginnings of that dynamic in the book but it has progressed much further than I grasped then. I pray for a religious renewal in America, which has happened before in the Great Awakenings. But I don’t have much of a clue as to how that will happen.

As to the basic argument, I would change little. It was persuasive enough to catch the eyes of a number of important evangelicals, but it has not really challenged the Reformed way of thinking that still dominates both the left and right of the Christian spectrum. However, for the moment it looks like “transformative” Christianity has been dramatically weakened by accommodation to or marginalization by the “world.”

Good and Bad Ways to Think About Religion and Politics

However, I did think the meaning of my book had to be taken further by putting it into a more accessible form. So, I wrote Good and Bad Ways to Think about Religion and Politics (Eerdmans, 2010. The book has received surprising attention and may make some dent on religious thinking on these matters. It has been used widely and a Lutheran clergyman even wrote a study guide for it.

The immediate occasion for writing on this topic again was increasing irritation on my part at the tendency in public discussion to mistake the constitutional separation of church and state for the interaction of religion and politics. The latter is constitutionally, historically, and theologically necessary, and cannot be mistaken for separation of church and state. Following from that confusion was the worry on the part of progressives that conservative religion’s involvement in politics was dangerous and should be curtailed. No problem with liberal activism, which followed the progressive agenda.

In the book I list “separation” and “fusion” as the bad ways of relating religion and politics. Both categories provide a rich occasion for discussion. “Separation” is pressed externally by the progressive commitment to keep dangerous religion out of the public sphere. But separation is also pressed internally by churches who historically refuse to involve themselves in politics, and more recently by serious groups of Christians who think a strategic withdrawal from politics is warranted in view of the post-Christian hostility to religion in public life. Christians have lost the culture wars so should withdraw into disciplined enclaves that will be able to survive and strengthen under pressure from “soft totalitarianism” or even persecution.

The second bad way, “fusion” of an organized Christian tradition with a political party or ideology is a very destructive way to relate religion and politics. It politicizes religion, which damages serious religion’s transcendent and universal Gospel. There is fusion on the left and right, which is sad indeed. Serious Christianity must keep its message free of such fusion for the sake of the Gospel.

Critical Engagement by the Public Theologian

After dealing with the bad ways, I propose what I call “critical engagement.” It assumes that there are many steps serious political theologians take when they journey from core Christian moral and religious values to actual political choice. Christians of good will and intelligence part company as they take those multiple steps from core to political choice. There are few “Christian” policies. Therefore, Christians who find their ultimate solidarity in sharing commitment to their One King, Jesus Christ, should be tolerant and generous with each other as they part company in the politics of the earthly kingdom. Not everything goes, however, there are some policies and politics that are beyond the pale and all Christians need to reject them. It takes great wisdom and courage to identify and resist such evil.

Further, there are some Christian core commitments that should make their way through those many steps to common political agreement for most Christians: protection of life at its beginning and end, religious liberty, and a substantial safety net for the poor.

With that approach in mind, I taught religion and politics in the fall of both 2016 and 2020 to large groups of lay people at St. John Lutheran…50 in 2016 and 120 in 2020. I had a bit of trepidation in doing so because the elections were so laden with passion and confusion. I spent a good deal of time forging the conviction in the classroom that our fundamental identity was established “in Christ,” and that our political commitments were secondary and should not be the basis for division in the Body of Christ.

We then went through the dangers of separation and fusion and then approached “critical engagement.” By that time the large groups were talking together and people were even publicly identifying their political commitments. I was astounded that they felt solidarity enough in Christ that they could hold their political choices loosely enough to reveal them without being combative. So we worked through “critical engagement” in 2020 with the clear and public assumption that one could vote for Biden or Trump without giving up their Christian identity.

My experience in both years indicated that my Lutheran approach really did work to diminish the angers of polarization and yet encourage Christians to take up their political calllings.

Public theology should heed the Lutheran approach to the way that serious Christianity and serious politics should be related. It does not separate or fuse but finds a lively way for Christians to exercise their calling as citizens. Amen! Ha.

Fourth Question: You say, “Therefore, the paradoxical vision rules out salvific politics. All human efforts are relativized before the gospel. They belong in the penultimate sphere.” Robert Benne. Paradoxical Vision (Kindle Locations 757-758). Kindle Edition. Do you, like the prophets of ancient Israel, warn megalomaniac leaders against self-idolatry?

I did that a number of times, I hope.

Conclusion

Perhaps you the reader noticed something in the pensive work of Robert Benne you might not see in other public theologians, namely, the distinction between the Lutheran posture and other postures toward political thought. The double-vision Benne draws from Augustine’s distinction between the earthly city and the city of God along with Luther’s distinction between law and gospel cannot help but structure a paradoxical vision. This leads the public theologian perpetually to keep in mind the distinction between the penultimate and the ultimate.

In Carl Braaten’s honorific treatment, he writes…

Benne proceeds to construct a framework for doing public theology in a Lutheran way. The first point to make clear is that the gospel of salvation is exclusively God’s work and cannot be co-opted by humans to claim divine endorsement of any political, economic, or social schemes to make this a better world. (Carl Braaten, A Harvest of Lutheran Dogmatics and Ethics, Fortress, 2021) p.94).

The gospel reminds us of God’s ultimate grace. The law reminds us that every penultimate striving for justice begins with God’s lure but still stands under God’s judgment.

Here is how we find this dialectic within a social statement produced by the ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America), The Church in Society: A Lutheran Perspective (1991). This social statement relies on what I have referred to elsewhere as discourse clarification as the means for taking up the prophetic task.

As a prophetic presence, this church has the obligation to name and denounce the idols before which people bow, to identify the power of sin present in social structures, and to advocate in hope with poor and powerless people. When religious or secular structures, ideologies, or authorities claim to be absolute, this church says, “We must obey God rather than any human authority” (Acts 5:29).3 With Martin Luther, this church understands that “to rebuke” those in authority “through God’s Word spoken publicly, boldly and honestly” is “not seditious” but “a praiseworthy, noble, and … particularly great service to God.” [3]

This has implications for the relationship of the church to the state. It also has implications for political theology as well as activism. On the one hand, the public theologian wants to light the fire that burns with passion for justice. On the other hand, we want to prevent this from turning into a wild fire that burns everything to ashes without our understanding why.

Here is my takeaway from Robert Benne’s work: do not expect salvation through politics. Yes, indeed, the public theologian like all persons of good will must rally commitment to justice, even transforming unjust institutions when necessary. But, given what we know about sin, never rely solely on human promises! Keep the vision of God’s kingdom ever before us as both judge and lure.

———-

[1] The world cannot be directly run by gospel love or the Christian virtues that are elicited by it. The world is run under the law, the “left-hand kingdom of God.” The law must and does account for the fallenness of the world. It demands and coerces. It holds persons responsible. It judges. It aims at the better amid a choice of worsts. (Robert Benne. Paradoxical Vision, Kindle Locations 1022-1025).

[2] “The paradoxical vision itself does not provide a substantive public theology, i.e., one that leads to specific policy positions. But, in addition to protecting the gospel, the paradoxical vision provides a framework that ought to condition Christian public theology’s assessment of human nature, of God’s governance of the world, and of the historical process itself. Within this framework provided by the paradoxical vision, Christian public theology can move in liberal or conservative directions. The framework itself does not move necessarily toward specific public-political ideologies, though it sets a general direction for such ideologies.” (Robert Benne. Paradoxical Vision, Kindle Locations 645-648).

[3] In the Journal of Lutheran Ethics, William Wood provides an illustrative example of Lutheran public witness in response to the Black Lives Matter Movement. “Both Luther and Bonhoeffer saw the state as the instrument of God, established by God to maintain law and order. Luther was clear, particularly in the Psalm 82 commentary, that the state was required to act for the benefit of its citizens and that, in response, the citizenry were obliged to obey the state and the church to stand aside while this balance applied. The complaint of the BLM movement and the evidence presented by Alexander and Forman has demonstrated that, for the African American community, the state has indeed failed in its role of providing law and order for the benefit of its citizens, creating a sub-class of citizenry. Since, then, the social contract is broken and the state has ceased to act as a legitimate state, both Luther and Bonhoeffer require the church and the individual Christian to take direct political action – in nuce to take up the prophetic mantle vis-à-vis the state. Following Bonhoeffer, the church is called to not only “bind up the wounds of the victims beneath the wheel but to seize the wheel itself.”

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Public Christian Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Public Christian Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

▓