Consciousness and Neuroscience in a Physical World

Did I lose my inborn sense of God to Atheism?

SR 2004 Sensus Divinitatis

An inborn sense of God? Really? You might not think so if you’re an atheist. One of my favorite atheists is Richard Dawkins at Oxford. Richard and I are not close friends, even though we have exchanged email communication. Has Dawkins’ brand of atheism stolen my inborn sense of God? Or, just buried it beneath a ton of gobbledygook?

We’re in the middle of a Patheos series on neuroscience and its implications for theological anthropology.

Did I lose my conscious mind to science?

Did I lose my Free Will to Science?

Did I lose my inborn sense of God to Atheism?

Did I lose my Self to my Brain?

Did I lose my Self to Determinism?

Did I lose my Self to Christian Freedom?

Now, to that brand of atheism that relies on scientific materialism.

The gods Richard Dawkins attacks

Richard Dawkins is as forceful as he is clear. He is attacking God. He says he is not attacking any specific divine figure such as Yahweh, Jesus, Allah, Baal, Zeus, or Wotan. Rather, he is attacking all of them at once. All belief in such divinities can be swept up into a single “God Hypothesis,” which Dawkins attempts to falsify. “I shall define the God Hypothesis more defensibly: there exists a super-human, supernatural intelligence who deliberately designed and created the universe and everything in it, including us.” Dawkins advocates “an alternative view: any creative intelligence, of sufficient complexity to design anything, comes into existence only as the end product of an extended process of gradual evolution” (Dawkins 2006, 31).

To say it another way, figures such as Yahweh, Jesus, Allah, Baal, Zeus, or Wotan are the products of the human psyche adapting to natural selection earlier in the evolutionary process. Imagining that such gods exist may have been adaptive for our ancestors. But, they are no longer adaptive for us moderns. Science is, though. Well, this is what Richard Dawkins believes to be the case.

Now, as a Christian public theologian, I will grant that the existence of the God of Israel should be considered a hypothesis. This is fair. This God hypothesis will not be confirmed or disconfirmed scientifically, however. It will be confirmed or disconfirmed experientially or eschatologically.

In the meantime, I would like to describe how theologians think. Christian theologians do not think like Dawkins or like similar atheists.[1] Just what do theologians in the Christian tradition think? Briefly, we think that you and I are born with an innate impulse to look for God. We have an innate psychic thirst for transcendence. How does that thirst get quenched? Does God offer us a cup of thirst quenching revelation?

What is true about God is not found in the thirst alone. Rather, what is true about God—that God is loving and gracious—must be tasted in God’s self-revelatory ambrosia. We don’t cook it up in our own kitchen. It is served to us.

Is there an Inborn Sense of God?

Each of us is born with a sense of the divine, a pre-thematized awareness of God. It takes an intellectual craniotomy to remove this portion of the spiritual cerebellum. It takes instruction, education, and self-discipline to rid oneself of this innate belief in God. To become an atheist takes considerable effort. Atheists are achievers, conquerors, heroes.

Here is St. Paul’s basic observation.

“Ever since the creation of the world his eternal power and divine nature, invisible though they are, have been understood and seen through the things he has made” (Romans 1:20).

In a recent Patheos post, “A Picture of God,” I interviewed Alice Rose, age 6, who drew a picture of God in chalk. In Alice’s picture, God is smiling. Why? Because God loves the world, she reports. Might Alice be responding to God through the things God has made just as St. Paul described?

An inborn sense of God belongs to our hard-core common sense intuition. It’s empirical. Systematic theologians call this natural revelation. Because of such natural revelation, it’s no surprise that we find numerous religious traditions sprouting up around the world.

God is telephoning us. Some of us look at our cell phone screen to see who’s calling. And then we tap “decline call.” But this does not remove our number from God’s directory.

Justice in eternity and time

That Bishop of Hippo in northern Africa who converted to Christianity only after much intellectual struggle, Augustine (354-430 AD), observed how you and I rely on a presupposed belief that justice is eternal. From within our inner souls, we “perceive what things are just, and what unjust” (Augustine 430, 11.27). Eternal justice might not in itself constitute God, to be sure. But it’s a signal of transcendence. It’s evidence that reality cannot be reduced to chemical cause-and-effect.

Justice is not empirical. It’s ideal. But by being ideal, it’s no less real. Justice transcends empirical actuality while being present to it.

Christians should be happy with justice-loving people who embrace a non-Christian religion or no religion at all. Certainly the Jew, Saint Peter, was affirming of justice wherever we find it when addressing his Greek friends. “I truly understand that God shows no partiality. In every nation anyone who fears him and does what is right is acceptable to him” (Acts 10: 34b-35).

We all know that an atheist can be a moral person, even high-minded and zealous toward what is good. This is because eternal justice inspires a temporal sense of fairness, rightness, and even zeal. However, to take the justice but not the God of justice is like a costumed child at Halloween taking the gift of candy without saying, “thank you.”[2]

My argument here is that our inborn sense of justice signals the presence of eternity within time. Templeton Prize winner physicist Frank Wilczek makes the same argument on the basis of beauty. For a lovely presentation see his video: “How Beauty Leads to Truth in Physics.”

Our inborn sensus divinitatis

“There is a certain general and confused knowledge of God, which is in almost all” of us humans, wrote Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) (Aquinas 1485, 1.2.1.ad.1). Note how Thomas thinks our confused knowledge of God belongs to “almost” all of us. Does this mean some of us escape confused knowledge of God?

Reformer John Calvin minces no words. It’s universal. “A sense of Deity [sensus divinitatis] is inscribed in every heart,” wrote John Calvin (1509-1564) (Calvin 1535, 1.3.1). This sensus divinitatis is present to the human psyche but not created by the psyche. Our sense of the divine is “one which nature herself allows no individual to forget, though many, with all their might, strive to do so” (Calvin 1535, 1.3.3).[3]

From pre-rational inborn sense of God to religious experience and revelation

The founder of Liberal Protestant theology, Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834), puts the sensus divinitatis in phenomenological terms. Our psyches exhibit a built in awareness of absolute dependence (Gefühl der schlechthinnigen Abhängigkeit). Even if we do not think about it objectively, subjectively we already feel the pre-rational pressure of anxiety over the fact that we are utterly dependent on that which transcends both our own existence as well as the existence of the whole world (Schleiermacher 1958).

It’s important to note that the sensus divinitatis does not present God to our mind as an object of thought. Rather, our mind perceives a pre-thematized signal of transcendence. According to Schleiermacher, this pre-rational awareness is the ‘particular characterized’ as ‘Sinn und Geschmack für das Unendliche‘, that is, a sense (or sensibility) and taste for the Infinite. We human people are finite creatures with an unquenchable thirst for the infinite.

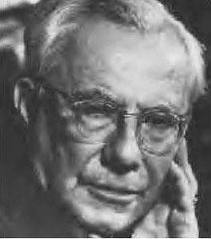

When we get to Paul Tillich (1886-1965), the sensus divinitatis or thirst for the infinite is turned into an existential question. Our very existence and our very dependence on that which is beyond us becomes the question. What is the answer? God is the answer. God reveals the divine self as an act of grace to answer the question of human existence.[4]

When we ask the question of God, we are “confused,” to use the words of Thomas Aquinas. We experience a sense of transcendence, but we cannot formulate objectively just what the ground of that transcendence is. The theologian, explicating special revelation, answers the question by pointing us to God.

But, alas, even in this answer God does not become an object of our thought. The word, ‘God’, along with symbols for God such as the mystical heavens or the depth of space keep God mysterious. Even in revelation, God remains mysterious. At least according to Roman Catholic giant, Karl Rahner (1904-1984).

“For what does Christianity really declare? Nothing else, after all, than that the great Mystery remains eternally a mystery, but that this mystery wishes to communicate Himself in absolute self-communication–as the infinite, incomprehensible and inexpressible Being whose name is God, as self-giving nearness–to the human soul in the midst of its experience of its own finite emptiness” (Rahner, Theological Investigations 1961-1988, 5:6).

This particular take on general revelation and special revelation is shared by virtually every contemporary Christian tradition: liberal Protestant, evangelical Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Orthodox. The only school of thought that rejects general revelation is neo-orthodoxy, specifically Karl Barth. Barth believes that our innate sensus divinitatis so distorts our image of God that it produces only idolatry. To avoid idolatry, says Barth, we must hear the Word of God.

The distorted sensus divintatis

Now, is the sensus divinitatis merely wishful thinking on the part of theologians who want to be persuasive? No. It’s much more than that. At least according to the Cognitive Science of Religion (CSR). “Cognitive science and theology both argue that belief in the divine is, at least to a certain degree, natural” (Greenway 2018, 252). Did you get that? The sensus divinitatis is natural, not supranatural.

What might a cognitive scientist observe? Because the sensus divinitatis apart from special revelation is pre-choate and pre-rational, left to itself it manufactures images like a young child with a crayon draws undisciplined colors on every blank piece of paper in the room. Barth was right. We can expect the sensus divinitatis to create idols–that is, images of the divine that lead us away from the truth of God.

In their treatment of this topic, Tyler Greenway and Justin Barrett appeal to CSR. Look at the brain. What does the brain do to our minds? Because our human minds enable us to operate with theory of mind and teleological reasoning, we “may err toward attributing supernatural ability to agents until limitations are learned, which may in turn dispose humans toward belief in super-able beings” (Greenway 2018, 244).

Does Dawkins’ list of gods he doesn’t like fit here–Yahweh, Jesus, Allah, Baal, Zeus, or Wotan? You betcha!

Calvin agrees with CSR that this is how we humans think. And he doesn’t like it. “Man’s nature, so to speak, is a perpetual factory of idols” (Calvin 1960, I. 1.11.). The theologian thinks of these as idols, not gods to be worshipped. More needs to be said about Yahweh and Jesus, to be sure. There is something about Jesus’ revelation of Yahweh that needs to be put into this equation.

What the theologian thinks is subtle. Even Yahweh and Jesus could become idols if belief in these would be twisted into self-serving idolatry. This subtlety is missed by atheist critics. But, theologians should not ask atheists how to think about God.

Greenway and Barrett wave at Jesus Christ to rescue us from manufacturing imaginary gods and supranatural beings. “The incarnate Christ seems to remedy the limitations of the sensus divinitatis…the incarnation provides a more precise semantic knowledge of God” (Greenway 2018, 249). Because God’s special revelation in incarnate, finite, and historical form, we gain knowledge of God mediated in objective terms that we can grasp. Six-year old Alice Rose, hyperlinked above, can grasp God’s smile as a signal that God loves the world. The revealed God–always risking idolatry in the form of a specific revelation–becomes the answer to the existential questions raised by the feeling of absolute dependence.

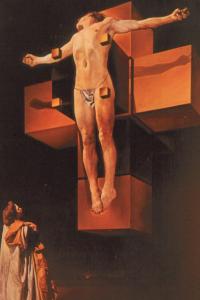

Theology of the Cross

So, we quench our thirst for the infinite by drinking the cup of revelation. Is that all there is to it? Not by a longshot.

Why? Because God’s self-revelation in Jesus Christ is by no means straight forward. On the one hand, Jesus is the image of God (eikon tou Theou). When we look at Jesus, we see God. On the other hand, Jesus’s light is cast in darkness. It’s easy to look at Jesus and miss seeing God. Why? Because what’s important about God is revealed under its opposite.

This is the point of the Theology of the Cross. Here is Martin Luther’s (1483-1546) way of saying it.

“When God makes alive, God does it by killing; when God justifies, God does it by making human beings guilty; when God exalts to heaven by bringing down to hell…God hides divine eternal goodness and mercy under eternal wrath, God’s righteousness under iniquity” (Luther 2016-2019, 178)

Luther interpreter Caryn Riswold adds.

“For Luther, it is the scandal of the cross that revealed the paradoxical nature of God. It is the event where we find life in death, birth in blood, freedom in bondage, and divine in human” (Riswold 2022, 30).

In the cross we see death, which reveals life. In the cross we see loss, which reveals gain. In the cross we see victimage, which reveals victory.

What is decisively important about God is that God is loving, gracious, forgiving, and promising.

Yes, this is a special revelation. But, one needs to know how to savor the taste to drink in the truth. Learning how to savor the taste is itself part of the special revelation experience.

An Inborn Sense of God? Conclusion

So, God remains a mystery even within revelation. What is revealed are personal characteristics of the divine mystery, the most important of which is that God is loving and gracious.

Might I lose my hard-core common sense intuition of God to atheism? Yes, if I surrender my inborn sense of God to the meat grinder of Dawkins’ rhetorical machinations. Atheist categories are like locked gates that close us from exploring the path to where our innate sense of God might lead us.

In the debate between atheists and theists over the existence of God, I hardly care about who wins. Far more important to me is the question: is God gracious? If God is not gracious, then I hardly care whether God exists or not.

▓

Ted Peters pursues Public Theology at the intersection of science, religion, ethics, and public policy. Peters is an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union, where he co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He previously authored Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom? (Routledge, 2nd ed., 2002) as well as Science, Theology, and Ethics (Ashgate 2003). He is editor of AI and IA: Utopia or Extinction? (ATF 2019). Along with Arvin Gouw and Brian Patrick Green, he co-edited the new book, Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics hot off the press (Roman and Littlefield/Lexington, 2022). Soon he will publish The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com. His fictional spy thriller, Cyrus Twelve, follows the twists and turns of a transhumanist plot.

▓

Notes

[2] To my example of justice, process theologian David Ray Griffin adds truth and beauty. “Genuine religious experience can be understood as the rising to consciousness of one’s direct prehension of the mind of the universe. Whereas our awareness of truth, beauty, and goodness as normative values involves our awareness of the content of our prehensions of one dimension of the cosmic mind, religious experience would involve more the awareness of the actual source of those values, or at least the subjective form of that prehension, which can be called the subjective form of ‘the holy’” (Griffin, 1998, p. 206). Here’s what’s important. Our human consciousness enjoys a direct prehension of justice along with beauty and truth. By these transcendental criteria, we judge what happens in human history. Griffin asks us to thank the deity who is the source of these values.

[3] This sensus Divinitatis, contends Calvinist philosopher Alvin Plantiga, is “a disposition or set of dispositions to form theistic beliefs in various circumstances, in response to the sorts of conditions or stimului that trigger the working of this sense of divinity” (Plantiga 2000, 173).

[4] “The method of correlation explains the contents of the Christian faith through existential questions and theological answers in mutual interdependence” (Tillich, Systematic Theology 1951-1963, 1.60).

References

Aquinas, Thomas. 1485. Summa Theologica. https://www.newadvent.org/summa/. Paris: New Advent.

Augustine. 430. City of God. https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/1201.htm.

Calvin, John. 1535. Institutes of the Christian Religion . Tr. Thomas Norton: https://www.ccel.org/ccel/calvin/institutes.toc.html.

—. 1960. Institutes of the Christian Religion, 2 Volumes. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox.

Dawkins, Richard. 2006. The God Delusion. New York: Bantam.

Dunford, Chris. 2022. Charles and Emma Darwin: The Option to Believe. Eugene OR: Wipf and Stock.

Griffin, David Ray. 1997. Unsnarling the World-Knot. Berkeley CA: University of California Press.

Greenway, Tyler, and Justin Barrett. 2018. “Cognitive Science, Sensus Divinitatis, and Christ.” In Christ and the Created Order, by eds Andrew B Torrance and Thomas H McCall, 239-252. Grand Rapids MI: Zondervan.

Luther, Martin. 2016-2019. The Bondage of the Will (1525) / The Annotated Luther, 6 Volumes. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Plantiga, Alvin. 2000. Warranted Christian Belief. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rahner, Karl. 1961-1988. Theological Investigations. New York: Seabury.

Riswold, Caryn. 2022. “Already Freed Christians Should Serve (Cake): Religious Freedom Claims and Christian Privelage .” In The Crux of Theology: Luther’s Teaching and OUr Work for Freedom, Justice, and Peace, by eds Alan G. Jorgenson and Kristen E. Kvam, 20-42. Minneapolis MN: Frotress.

Schleiermacher, Friedrich. 1958. On Religion. New York: Harper.

Stenmark, Mikael. 2012. “How to Relate Christian Faith and Science.” The Blackwell Companion to Science and Christianity. Eds., J.B. Stump and Alan G. Padgett. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 63-73.

Tillich, Paul. 1951-1963. Systematic Theology. 1st. 3 Volumes: Chicago: University of Chicago Press.