What is History in Big History?

Our main question is this: what is history in Big History? But let’s first ask: what role does history play in today’s controversies? Let’s take Black History as an example.

Should our high school students register for an Advanced Placement course in African American Studies? Should young people learn the history of slavery in America, Jim Crow segregation, the Civil Rights Movement, and Critical Theory? Does this frighten you? Encourage you?

The prospect of African American history terrifies those who grew up with a different account of the past. What is history that it might frighten anyone?

African American Studies proponents want history to become a truth-exposer and an identity-former. Might this frighten some but encourage others?

Such history scares Florida governor Ron DeSantis. The governor has threatened to ban the teaching of black history in his state. The College Board overseeing the curriculum ran into a political buzz saw. So, the board revised the proposed course, eliminating potentially controversial subtopics such as Critical Theory. Writing in the New York Times, Anemona Hartocollis and Eliza Fawcett recognize how history divides.

“If anything, the arguments over the curriculum underscore the fact that the United States is a country that cannot agree on its own story, especially the complex history of Black Americans.”

The architects of Big History similarly want to retell our history in an altered way. They want to change our history to change the way we think. Big historians want us to think naturalistically.

This makes me want to ask: just what is history anyway? Specifically, what is history in Big History? What is history in cosmic history?

What is history in Big History?

We’re asking: what is history in Big History (BH)? As we saw in previous Patheos posts, our BH colleagues nest human history within evolutionary accounts of the cosmic story since the Big Bang. Big history is constructed on a foundation of evidence-based science. History in BH gives an account of energy flow, information, learning, organization, as well as interaction with the environment. Given this range of interest, historians exclude by omission the supernatural along with religions which believe in the supernatural.

I continue to admire and applaud Big History for including the scientific story that postulates a framework of deep time, perhaps 13.8 billion years. Yet, I worry somewhat that big historians may have surreptitiously imported not science but rather naturalism or even atheism into their presuppositions.

The religions of the book – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam – are already historically conscious. Jews, Christians, and Muslims lived and recorded history long before scientists and their BH interpreters came along. But big historians do not like history the way Jews, Christians, and Muslims tell it. So, history in Big History tells a different story. This leads me to ask: just what counts for history in Big History?

Is the concept of history in Big History truncated? Slanted? Ideological? What would Governor DeSantis think?

Of particular concern to me is this question: is BH deaf to questions of transcendence? If so, then perhaps Cosmic History is a better term than Big History. Within Cosmic History (CH) we can explore transcendence and ask the God question.

So, let’s ask: just what is history anyway?

One of features of the evidence-based science upon which history in Big History is constructed is that it excludes consciousness. As philosopher Ernest Nagel and many others have pointed out, natural science is doomed to remain incomplete until it takes the very consciousness of the scientist into account. This is relevant to our question – what is history in Big History? – because there is such a thing as the history of human consciousness.

So, let’s keep asking: just what is history anyway?

John Herman Randall at Columbia University combines fact with significance in defining history.

The term history “is a double-barreled word: it means both what has happened, Geschichte–was geschieht–and the knowledge and statement of what happened, historia” (Randall 1958, 29).

History is a story about contingent events plus their meaning. That’s my core definition.

What Happened + What It Means = History

We all know what history is, right? (Peters 2017) Or at least we think we know what it is. Since we can remember, we’ve studied history in school. Typically, historians compile stories of kings and wars and countries and politics and economics and sometimes art and music. History collects stories about human beings in various periods of time. That’s history.

Well, that’s the history we are familiar with. AP African American Studies makes history smaller by turning a specific history into a truth-exposer and an identity-former.

Our concern here, as announced above, is that history is about to get bigger, much bigger. Both BH and CH include human stories, to be sure. But they include nature’s story as well. Now we ask: can Big History become a truth-exposer or identity-former?

Let me repeat my definition: the discipline of history is the chronicle and interpretation of past contingent events.

Note that word, contingent. This is the opposite of predetermined. It is the opposite of necessary. For an event to be contingent, it means the event could have happened differently than it did. Because we human beings are free creatures and because we make unpredictable decisions, human history becomes as unpredictable as it is fascinating.

Nature too has contingent events. Even the Big Bang is a contingent event. Evolutionary history is replete with contingent twists and turns.

For any history to be interesting, we must call to mind its contingent events.

The History of Leaps in Consciousness

Among the contingent events to be chronicled are jumps in human consciousness. Human consciousness has not always been what we today understand it to be. What goes on within the human mind has changed over time. This change cannot be described as a gradual evolution. Rather, the history of human consciousness is punctuated with leaps, leaps in cognition, leaps in knowingness, leaps in self-awareness.

I believe the axial threshold should be studied by the big historian, because it marks a leap in human consciousness. The term, Axial Age (Achenzeit), given us by German philosopher of history Karl Jaspers (1883-1969), refers to events shocking the human psyche occurring in different parts of the world between 800 and 200 before the common era (Jaspers 1953).

Transcendence and ultimacy spoke to human consciousness through selected individuals. This experience is recorded in the ruminations of Confucius, Laozi, the Upanishadic Brahmans, Buddha, Zoroaster, the Hebrew prophets, and Plato. Whether theists or non-theists, these thinkers cultivated belief in a transcendent moral order and ground for human reasoning that is trans-tribal and universal in scope. The axial leap in consciousness is itself a contingent event within history and worthy of study as a historical event.

From Compact to Differentiated Consciousness

The overall direction of the history of human thinking is from compact consciousness toward increased differentiation. Our compact or fundamental consciousness is immediate. We are so embedded in our experiential world that our self, our surroundings, and the fullness of reality are all immediately present to our awareness. When we learn to speak, however, this immediacy cracks, splits, and complexifies. We begin to mediate our understanding of the surrounding world through language and symbols.

The overall direction of the history of human thinking is from compact consciousness toward increased differentiation. Our compact or fundamental consciousness is immediate. We are so embedded in our experiential world that our self, our surroundings, and the fullness of reality are all immediately present to our awareness. When we learn to speak, however, this immediacy cracks, splits, and complexifies. We begin to mediate our understanding of the surrounding world through language and symbols.

In fact, we even mediate our self-understanding through the words we are taught along with the definitions of these words supplied usually by our parents. We know how it feels to be called a “bad boy” or a “good girl.” A linguistically mediated self-understanding is a differentiated self-understanding; yet it is still tied inextricably to our immediate environment.

The process of differentiation does not stop with speaking. Writing adds complexity. Writing extricates us from our immediate surroundings. Reading what was written many years prior provides our mediated self-understanding with a history. We see ourselves as belonging, as participating meaningfully in a reality spread out in time. We self-evaluate on the basis of this internalized historical consciousness.

Historical Consciousness

We’re asking: what is history in Big History? One matter is obvious. Big historians exhibit a certain level of historical consciousness. What’s that?

Historical consciousness (HC) includes two elements important to us here. First, we think of the past as dead and over. Yet, at the same time, we form our own identity selectively from the past we remember. So, secondly, dead past events live on in our psyches through the nuances in the words we speak and symbols we live by. Our identity is formed by the past we remember and even influences we never heard of.

Consciousness of Consciousness

It is rare that we step out of our historically conditioned self-understanding and look at ourselves critically. Yet, when we do examine our own consciousness critically, we become conscious of our consciousness. We are then able to subject the historical accounts we’ve inherited to critical analysis and to re-thinking. This re-thinking liberates us partially from our past and makes self-transcendence possible.

Borrowing a term from philosopher of history Eric Voegelin (1901-1985), I call this a leap in consciousness (Voegelin 1956-1987).

The Leap to Transcendental Shock

One leap takes us from a historically conditioned first naiveté into critical consciousness. Critical consciousness, which I just alluded to, is consciousness of our consciousness. It is awareness of our awareness.

Another leap takes us from this world to another, from everyday reality to transcendence, from the physical to the spiritual. When this happens, we experience transcendental shock.

For some of us, our self-understanding becomes jolted when confronted by transcendent reality. Like a 220-volt shock from an electrical outlet, God’s self-manifestation in our life splits reality into the less real and the more real. Spiritual shock jolted our historical ancestors into a new way of looking at self, world, and the divine.

In the premodern or archaic world, these leaps to differentiated consciousness probably occurred first in individuals. Then it spread to groups. Eventually it swept up entire cultural epochs.

The process of differentiation of consciousness is not the same thing as growth in intelligence. I recommend we work with the assumption that our earliest hominin ancestors were equal to us in intelligence. What distinguishes them from us is the stage of differentiated consciousness, not brain power. Our ancestors were just as intelligent as we are, even if they thought differently. They thought differently in part because they didn’t have Google to overwhelm them with competing sources of information.

These historical leaps in consciousness are not revolutionary in the sense that they jettison previous modes of awareness. Rather, leaps are cumulative. Early sensibilities continue to abide while increasing in complexity and nuance.

Conclusion

One task of history within Big History, I believe, should be to chronicle and interpret leaps in consciousness. One leap of particular interest is the Axial Threshold. Unfortunately, this concern is not as central to practicing big historians as I would like to see.

That’s why I prefer the term, cosmic history. Within cosmic history, we can include in our story accounts of consciousness of consciousness right along with experiences with transcendence. Then we will be ready to ask: what does this all mean?

When we combine what happened with what it means, we get robust history.

Patheos SR 5054 BH 4 What is history in Big History?

For more on our analysis of Big History, start clicking.

Patheos SR 5051 BH 1 Science, Religion, and Deep Time

Patheos SR 5052 BH 2 Science and Religion in Big History

Patheos SR 5053 BH 3 Teilhard and Big History

Patheos SR 5054 BH 4 What is history in Big History?

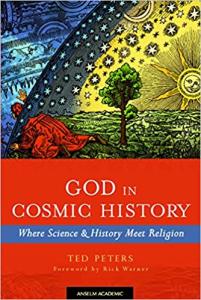

Patheos SR 5055 BH 5 God in Cosmic History

Patheos SR 5056 BH 6 Big History and Evangelical Theology: Roger Olson

Patheos SR 5058 BH 8 Big History, Religious Naturalism, and Ursula Goodenough

Patheos SR 5059 BH 9 Big History and Progressive Christianity: Thomas Lindell

Patheos SR 5060 BH 10 Critique of Ted Peters by Mitchell Diamond

Patheos SR 5061 BH11 Trinitarian Big History: Chris Barrigar

▓

Ted Peters pursues Public Theology at the intersection of science, religion, ethics, and public policy. Peters is an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union, where he co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He tackled the implications of genetic innovation for the future of humanity in Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom? (Routledge, 2nd ed., 2002) as well as For the Love of Children: Genetic Technology and the Future of the Family (Westminster/John Knox 1997). His essays are collected in Science, Theology, and Ethics (Ashgate 2003) The Voice of Public Theology (ATF 2023).

Recently Ted edited AI and IA: Utopia or Extinction? (ATF 2019). Along with Arvin Gouw and Brian Patrick Green, he co-edited the new book, Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics hot off the press (Roman and Littlefield/Lexington, 2022). His fictional spy thriller, Cyrus Twelve, follows the twists and turns of a transhumanist plot.

Visit Ted Peters’ website, TedsTimelyTake.com.

▓

References

Christian, David, Cynthia Stokes Brown, and Craig Benjamin, eds. 2014. Big History Between Nothing and Everything. New York: McGraw Hill.

Jaspers, Karl. 1953. The Origin and Goal of History. London: Routledge.

Peters, Ted. 2017. God in Cosmic History: Where Science and Big History Meet Religion. Winona MN: Anselm Academic ISBN 978-1-59982-813-8.

Randall, John Herman. 1958. Nature and Historical Experience. New York: Columbia.

Voegelin, Eric. 1956-1987. Order and History, 5 Volumes. Baton Rouge LA: Louisiana State University Press.