Emergent Dualism. Soul 5

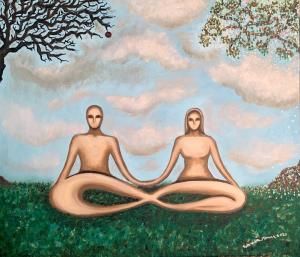

Adam and Eve. You and I. Will emergent dualism explain our souls?In this Patheos series on the soul we’ve begun with the biblical symbols and tried to construct concepts. The Bible tells us that we humans are slung between earth and heaven, body and soul, soil and spirit. Just what concepts should we construct that are both loyal to Scripture yet make coherent contemporary sense?

Here we look at two models: emergent dualism and nonreductive physicalism. In this post, we’ll tackle emergent dualism. Fasten your seat belt. It’s gonna be a rocky ride.

Soil and Spirit again

My starting point for every discussion of the soul is the Genesis creation account. God’s creation of the first human being is both dramatic and definitive.

NRS Genesis 2:7: “Then the LORD God formed man from the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and the man became a living being.”

Recall that the Hebrew word for “man” here is Adam, representing “humanity,” and the word for ground or soil is Adamah. We human beings are made from soil. Yet, we also share the breath of God. We are combinations of soil and spirit, earth and heaven, animal and more.

Genesis 2:7 provides the go-to biblical symbol. Now, how should the systematic theologian interpret this symbolic passage? As we have seen, many of our ancestors have thought metaphysically about this, positing a substance dualism between the physical body and the non-physical soul. In contemporary discussion, however, theologians are fleeing substance dualism like cats escaping the reach of a lawn sprinkler.

To where do those theologians hurry to escape the reach of dualism? Do they end up at physicalism? Materialism? Monism?

If theologians want stop at an oasis before running all the way from substance dualism to reductionist physicalism, there are welcoming off ramps. At least two: emergent dualism and nonreductive physicalism. Let’s take a look at emergent dualism here.

Emergent Dualism

According to supporters of Emergent Dualism, we may still speak of human beings as possessing a soul. It’s just not an immortal soul. What distinguishes this position is where the soul comes from. Recall how for substance dualists—what some dub constitutional dualism–the soul comes from a special and individual act of God’s creation. For emergent dualists, however, the soul emerges for the human race through evolution and it emerges in the individual through fetal development. First comes the body. Then comes the soul. The soul is an emergent property.

The core meaning of ‘emergence’ is that when material elements of a certain sort are assembled in an optimum way, something new and more complex comes into being. The whole that emerges is something that had not existed before. Some refer to this as ‘holism’ which indicates that new wholes are greater than the sum of the parts that made them up. Hence, when all the chemicals that make up the human body come together in an optimum way, a new whole—that is, a person—emerges. More. A soul emerges. This soul is distinguishable from the body and brain that had been its source.

Emergent Dualism in Theological Controversy

Huntington University philosopher William Hasker asserts that emergent dualism makes for “both good philosophy and sound theology.”

“Emergentism presents us with a compelling picture of the co-evolution of mind and brain. Among the emergentist options, emergent dualism is the one that best satisfies the requirements of both good philosophy and sound theology.”

A Christian theologian who embraces emergent dualism probably rejects immortality of the soul yet embraces resurrection of the body. Dean Zimmerman, a professor of philosophy at Rutgers University, for example, anticipates our resurrection as a spiritual body.

“In every case, resurrection is a miracle performed by God. On my model—same person, different body, no soul—there is not a new person in the resurrection; there is only a new body, a spiritual body. Admittedly, I don’t know what a spiritual body would be like, but I am confident that no immaterial soul is required.”

The emergent soul is not the essence of the person, according to Zimmerman. What God resurrects is the whole person, accordingly. Our resurrection takes the form of a “spiritual body.”

Richard Swinburne at Oxford and Tim O’Conner at Indiana might be upset at emergent dualism. They hold that…

“…the normal Christian view that we continue to exist after death before and the general resurrection. And since our bodies are decayed and in the ground, it must be the soul which if we don’t have a soul, we don’t continue to exist. But more importantly, the soul is the vehicle of our identity. “

This prompts objections from Zimmerman’s critics such as Lynne Rudder Baker.

“Emergent Dualism foregoes one supposed advantage of traditional dualism—namely, that souls could exist separated from any body. If there is no possibility of separated souls, then Emergent Dualism has no advantage over nondualistic positions like the Constitution View.”

Emergent Dualism?

In sum, there are three key tenets to the emergent dualist position. First, what we know as the soul evolves from a physical substrate over time. Second, our soul replete with mental and spiritual properties represents an emergent level of complexity that is not reducible to its physical past. Human mentation, culture, and spirit have emerged with a new substantial status. Third, the emergent soul dies. In the resurrection, the whole person is raised, not merely the soul.

Nonreductive physicalism is similar. The nonreductive physicalist accepts the idea of emergence in emergent dualism. But it rejects assigning independent substantial status for the emergent soul or mind. To nonreductive physicalis we will turn in our next Patheos post.

Conclusion

What most of the positions on this spectrum mentioned thus far have in common is the close connection between the soul and the mind. This means that the presence of soul applies to a large but limited segment of the human population, namely, those persons after fetal brain development in infancy and prior to brain deterioration in old age. What is missing, from my point of view, is the idea that the soul is more comprehensive than the mind. It is not unusual to believe that the human soul belongs to the essence of personhood, a personhood that is not reducible to active thinking.

Regardless, when we think about eternal life with God, we cannot dodge one incontrovertible fact: it is up to God and God alone to determine our resurrection. Christian theologians who flirt with either emergent dualism of nonreductive physicalism seem to be clear on this matter. Their task becomes one of constructing a coherent concept of the soma pneumatikon, spiritualized body.

ST 4135. Emergent Dualism. Soul 5.

▓

Ted Peters (Ph.D., University of Chicago) is a public theologian directing traffic at the intersection of science, religion, and ethics. Peters is an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union, where he co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. He recently co-edited Astrobiology: Science, Ethics, and Public Policy (Scrivener 2021) as well as Astrotheology: Science and Theology Meet Extraterrestrial Intelligence (Cascade 2018). He also co-edited Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics (Lexington 2022) and The CRISPR Revolution in Science, Ethics, and Religion (Praeger 2023). Peters is author of Playing God: Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom (Routledge, 2nd ed, 2002) and The Stem Cell Debate (Fortress 2007). See his blogsite [https://www.patheos.com/blogs/publictheology/] and his website [TedsTimelyTake.com].

▓