Is “Our Confession of Evangelical Conviction” the New Barmen?

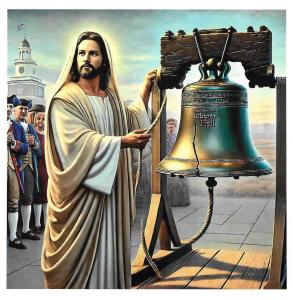

If has not been clear up to this point, America’s evangelical Christians cannot be exhaustively reduced to Christian Nationalism or justifiably villified as Trump’s acolytes. Our Confession of Evangelical Conviction, quite like the Barmen Declaration, makes it clear that Jesus Christ is king of kings. And this means no political leader should usurp that office.

What does Our Confession of Evangelical Conviction say?

The document of September 9, 2024 — penned by lead author Sky Jethani — does not name Donald Trump or the MAGA wing of the Republican Party. Rather, it names Jesus Christ. When our loyalty is given to the transcendent kingdom of God, then no temporal or evanescent political power can claim our ultimate fealty. Nor should competing political opinions within the Body of Christ divide the Body of Christ.

We affirm that Jesus Christ is God’s Son and the only head of the Church (Colossians 1:18). No political ideology or earthly authority can claim the authority that belongs to Christ (Philippians 2:9-11). We reaffirm our dedication to his Gospel which stands apart from any partisan agenda.[1]

We reject the false teaching that anyone other than Jesus Christ has been anointed by God as our Savior, or that a Christian’s loyalty should belong to any political party. We reject any message that promotes devotion to a human leader or that wraps divine worship around partisanship.

Our Confession of Evangelical Conviction now emblematizes an identifiable evangelical cohort that looks quite different from Christian nationalism.[2] Kristin du Mez and other Christians against Christian Nationalism have signed it.

What does the Barmen Declaration say?

The Confessional Synod of the German Evangelical Church (Bekennende Christen) met in Barmen, May 29-31 1934. The German context at the time was similar to Our Confession of Evangelical Conviction. At that time, the Nazi Party under the leadership of Adolph Hitler was spewing divisive invectives against Communists, children with mental or physical disabilities, Gypsies, LGBTQ+ persons, Jews, and inferior races. It was difficult for Christians who wished to be patriots and good citizens to decide with confidence what to do. The Barmen Declaration helped to draw a thick red line to make clear what stand fits the Christian commitment to faith, hope, and love.

As members of Lutheran, Reformed, and United churches we may and must speak with one voice….Jesus Christ, as he is attested for us in holy scripture, is the one Word of God which we have to hear and which we have to trust and obey in life and in death….We reject the false doctrine, as though the church were permitted to abandon the form of its message and order to its own pleasure or to changes in prevailing ideological and political convictions.

Armed with the Barmen Declaration, an anti-Nazi resistance could coalece. Might Our Confession of Evangelical Conviction have to play such a role in America’s near future?

PT 3252 Is “Our Confession of Evangelical Conviction” the New Barmen?

PT 3240 Barmen on Christian Nationalism

PT 3247 Anti-Anti-Christian Nationalism, Part 1

PT 3248 Anti-Anti-Christian Nationalism, Part 2

PT 3249 Anti-Anti-Christian Nationalism, Part 3

Christian Nationalism Resources

▓

For Patheos, Ted Peters posts articles and notices in the field of Public Theology. He is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union. His single volume systematic theology, God—The World’s Future, is now in the 3rd edition. He has also authored God as Trinity plus Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society as well as Sin Boldly: Justifying Faith for Fragile and Broken Souls. He recently published. The Voice of Public Theology, with ATF Press. See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com and Patheos blog site on Public Theology.

▓

[1] One very whiney even blubbering collection of invectives appears in a blistering critique of Our Confession of Evangelical Conviction by Patheos columnist Anthony Costello. According to Costello, the evangelical confessors can’t get anything right, not even allegiance to Jesus Christ.Now, let’s think carefully about loyalty, or allegiance, for a moment; more carefully than these “leaders” seemed to have thought about it. As to allegiance, or loyalty, do we have no allegiances or loyalties other than Christ? For example, are you married? Do you have children? Do you work for a company or business or teach at a school? Do you have friends? Do you have any allegiance to your country?

[2] At least one critic, Andrew T. Walker, faults the “Our Confession of Evangelical Conviction” for failing properly to distinguish nature and grace. “The new statement is confused over the relationship between nature and grace. It ends up telling us almost nothing about how to properly relate Christianity to politics. It becomes a vacuous declaration that one gets the impression is a way to tsk-tsk rightward-facing evangelicals….Politics and government are creation-order institutions meant for the common good of all. There’s no redemptive narrative wrapped up in politics. It’s about the stewarding of power for the benefit of all. The government’s authority is derivative of God’s authority. Government—and therefore, power—aren’t intrinsically wrong things. It means, among many possible pursuits pertaining to the common good, securing the rights of individuals to live (so “no” to abortion), upholding the truth about our embodiment as males and females (so “no” to transgenderism), promoting the natural family as society’s cornerstone (so “no” to same-sex marriage), and securing liberty to live in accordance with the truth (so “yes” to religious liberty).”