I have a new post at Sojourners’ God’s Politics blog on maternal mortality and its connection to current controversies about birth control and whether it fosters a culture that’s “anti-life.” Here’s a bit of it:

Not long ago, a Christian woman experienced in grassroots mission work in east Africa told me that one of the saddest things she encountered was the attitude of resignation on the part of people living in extreme poverty. She said something along these lines:

“When a baby dies, say, it’s accepted as the will of God. Not that they do not grieve — of course they do. It’s just that they don’t question it, whereas we, as Westerners, see the outrage of children dying of preventable diseases as just that — outrage. But they are so used to it.”

Indeed, the frequency of infant or maternal deaths in parts of the world can foster a sense of inevitability. In the country where my family and I are headed, Malawi, a woman’s lifetime chance of dying in childbirth is 1 in 36, around where it was in the US when Mathilda Shillock wrote to her sister of her desire to stop having babies.

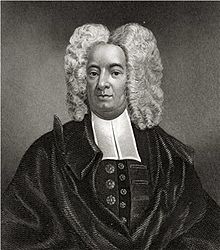

Puritan minister Cotton Mather (who himself saw eight of his 15 children die before reaching the age of two) advised pregnant women that “preparation for death is that most Reasonable and Seasonable thing, to which you must now apply yourself.” Writings from women in this period indicate that death was uppermost in their minds as they prepared to give birth.

Perhaps it isn’t surprising that in many societies — not least, in Christian societies, who may have frequently understood suffering in childbirth as what women ‘deserve’ post-Fall (even opposing pain relief) — “mythological or theological explanations [explained] why women should suffer in childbirth, [forestalling] efforts to make the process safer.” Suffering and death was, as they understood it, the will of God.

And so I can’t help feeling that while some of the concerns about the effects of a “birth control culture” may be valid, I also worry that to deny women access to contraception — especially when we’re talking about women in the developing world — -is to trivialize what more children means in a place like Malawi, or, say, Somaliland, where women have a 1 in 14 lifetime risk of dying in childbirth.

Read the rest here. Have a great weekend!