Chicago Tribune reporter Steve Chapman recently wrote a startling piece entitled “The iPhone X Proves the Unabomber Was Right.”

Come on. How can you not click on that? Obviously it’s clickbait (Chapman of course does not condone the bombings carried out by Ted Kaczynski) but its point is fascinating and critically relevant.

By now you must have heard of the upcoming iPhone X, which Apple is bragging about with the tagline: “The Future is Here.” This is a clever bit of marketing, but it obviously reminded Steve Chapman of something more chilling: a decades-old warning about the future, from one of the most notorious domestic terrorists in US history.

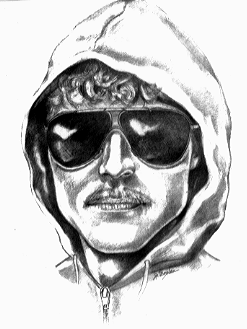

The Unabomber (a strange portmanteau of University-Airline-Bomber) was the name given by the press to an anarchist terrorist named Ted Kaczynski, who carried out fourteen successful bombings (and two unsuccessful ones) between 1978 and his capture in 1995. He killed 3 people and injured around two dozen others.

Kaczynski, who continues to write and publish from prison, is what’s called a primitivist. Anarcho-primitivism is a strange little ideology which can be difficult to place on a normal two-dimensional political compass; it has both left and right variations.

Like all forms of anarchism, it rejects authoritarianism completely (Kaczynski’s beliefs on this aspect are unclear and have changed). It is unique in that it also rejects most forms of technology, advocating that humans engage in “re-wilding”and returning to a pre-industrial (and sometimes even pre-neolithic) way of life.

This is evident in Kaczynski’s own writing. His acts of terrorism were carried out with the specific goal of publishing a manifesto entitled Industrial Society and Its Future; he promised to cease mailing out bombs if a major outlet would do so. The New York Times and Washington Post both capitulated on the advice of the FBI and this led to Kaczynski’s capture. The Unabomber pleaded guilty, refusing to use the insanity defense his lawyers recommended, and will spend the rest of his life in prison.

Despite his methods, Kaczynski has developed a bit of a following among several intellectuals who either believe in or are sympathetic towards anarcho-primitivism. It is easy to understand why this is the case for people who hold to a neo-Luddite perspective on the world; despite his manifesto’s litany of spelling and grammatical errors, Kaczynski was obviously very naturally intelligent and well-read. Industrial Society taps into very real fears about the changing landscape of technology (fears which people like Elon Musk continue to stoke), the proliferation of globalization, and an increasingly automated economy. These fears are perhaps even more relevant now during late capitalism as they were twenty years ago at the outset of neoliberalism’s ascendance.

But Kaczynski’s analysis – the part that Chapman takes to heart in his piece – misunderstands the relationship between human beings and technology. Kaczynski writes, quoted by Chapman:

Once a technical innovation has been introduced, people usually become dependent on it, so that they can never again do without it, unless it is replaced by some still more advanced innovation. Not only do people become dependent as individuals on a new item of technology, but, even more, the system as a whole becomes dependent on it.

Think of smartphones; just a decade ago they were a curiosity, or perhaps a status symbol. Now they are a requirement for anyone to survive in the western world. Presumably, companies like Apple will keep introducing new innovations, like the facial recognition software built into the iPhone X, that will eventually become standard and then a necessity. Chapman himself writes, echoing a theme of Industrial Society:

But [technological advances] happen whether they are worth it or not, and the individual has little power to resist. Technological innovation is a one-way street. Once you enter it, you are obligated to proceed, even if it leads someplace you would not have chosen to go.

In this view, technological advancement simply happens, spurred on by forces greater than the sum of their parts: individuals, and even societies, are unable to stop or control the march of technology at its most fundamental level.

But Chapman’s pessimism is a function of his liberalism; he, like most Westerners, is profoundly unable to conceive of a reordered society that has a different relationship to technology than the one our current liberal-capitalist society has. The worry – that rapidly-advancing technology can change our society for the worse – is only half-correct; it is rooted in materialism, but it is not dialectical and so cannot conceive of a solution.

Kaczynski obviously thought of this, because he devotes significant attention in Industrial Society to attacking what he calls “modern leftists.” His take on leftism is profoundly pessimistic, emphasizing that his virulent criticisms (which mainly focus on the Left’s use of identity politics and sound eerily like things a Trump supporter might say) do not apply to the leftists of the 19th and early 20th centuries. He views Leftism in the wake of the collapse of the USSR as a “fragmented” ideology and states that “it is not properly clear who can be called a leftist.” He attacks “The Psychology of Modern Leftism” and surmises that Leftists are driven by “feelings of inferiority,” which leads them to identify with the downtrodden and oppressed; he roundly attacks “political correctness.”

Kaczynski’s conception of Leftism is a hodgepodge amalgamation of actual leftists (socialists, communists, et al), social-justice focused liberals, and post-modernist bourgeoisie academics and thus his critique falls flat. A true Leftist take on the problems Kaczynski was trying to address (the problem typified by the iPhone X, apparently) looks at our relationship to technology in a different light.

All of human society is production. Liberals and idealists don’t like hearing that, but it is the most important thing you can understand about the world. Nothing we humans have created – not buildings, institutions, beliefs, or identities – can be separated from what materials we have available to us, who controls the use of those materials, and yes, the level of technology we have to work those materials. Skyscrapers cannot exist without vast quantities of metals, the capabilities to transport those metals, the workforce necessary to construct them, and the architectural knowledge to make them stand. A religion cannot exist without people trying to make sense of the world around them, why they go hungry while others grow fat, why Caesar is called Son of God, why money-changers inhabit a Temple that is supposed to belong to God.

Under capitalism, technological advances, like all aspects of production, are geared towards maximizing profit. Chapman quotes Yuval Noah Harari as writing that inventions like email “revved up the treadmill of life to ten times its former speed and made our days more anxious and agitated.”

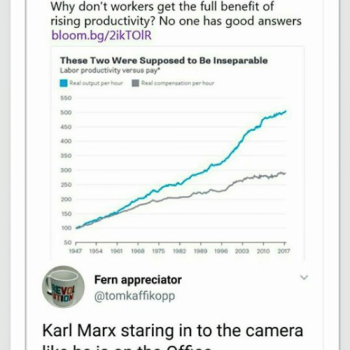

‘Revving up the treadmill of life’ is a fancy way of saying that these inventions have dramatically increased our productivity. The problem is that, under capitalism, there is never “enough” productivity. Bosses will seek to maximize productivity (without increasing wages) as much as humanly possible, because doing so increases surplus value and therefore profits.

We feel the effects of rapid technological improvement adversely because capitalism concentrates the benefits brought by technology in the hands of the owners of the means of production. Technology should free us from labor – if new technology means we can do in an hour what previously took two, then by all logic we should only have to work half as long.

But capitalism, with its constant need for growth and profit maximization, will not allow this. Technology can either lessen work or increase value – and it is obvious what capitalism prefers.

The thing is, we already produce enough wealth to feed, clothe, shelter, and care for every human being on this planet. There is simply no need to relentlessly increase productive output – what we need is to change the way resources are distributed. But capitalism cannot do that; if it is not profitable to save someone’s life, then we let them die.

With the abolition of profit, of private property, and of capitalism, production can be refocused on meeting human needs and all worries of a coming techpocalypse vanish. You will no longer need a smartphone, because your livelihood is not tied to your productivity. As legendary actor (and socialist) Charlie Chaplin once said, we must fight for “a world where science and progress will lead to all men’s happiness.”

Technology is not the enemy, despite what Steve Chapman and the Unabomber might think. It is a tool, just like everything else. What matters is how that tool is used, and by whom. Were the wealth of society held in common by every single one of us, then the iPhone X would lose all power over you. In fact, we wouldn’t be hearing about it at all.

Now isn’t that worth a revolution?