I run out of words to say how much I adore Jana Riess. (My enthusiasm embarrasses Jana to no end, but if you enjoyed Post-Traumatic Church Syndrome, she is the reason. Jana took my messy second draft through innumerable edits, and taught me how to write a book in the process.)

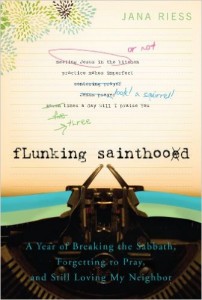

I first found Jana because of her funny, poignant memoir Flunking Sainthood: A Year of Breaking the Sabbath, Forgetting to Pray, and Still Loving My Neighbor, a book I highly recommend–both for its humor and inspiration.

“This wry memoir tackles twelve different spiritual practices in a quest to become more saintly, including fasting, fixed-hour prayer, the Jesus Prayer, gratitude, Sabbath-keeping, and generosity. Although Riess begins with great plans for success (“Really, how hard could that be?” she asks blithely at the start of her saint-making year), she finds to her growing humiliation that she is failing–not just at some of the practices, but at every single one. What emerges is a funny yet vulnerable story of the quest for spiritual perfection and the reality of spiritual failure, which turns out to be a valuable practice in and of itself.”

An Excerpt from FLUNKING SAINTHOOD

An Excerpt from FLUNKING SAINTHOOD

Six weeks after I turned in the manuscript for Flunking Sainthood, I received a surprising phone call. The father I had not seen or heard from in twenty-six years was dying in Mobile, Alabama. Could I come there to say good-bye? Oh, and one more little question: did I want the hospital to discontinue life support, since he was unresponsive and could not breathe on his own?

I was stunned. The day took on a surreal feeling as I called my husband, called the nurse, called the social worker, called the airlines. His condition was bad, the hospital told me. The pulmonologist wasn’t sure if he would even last the night. He was “actively dying” now, having been in the hospital for thirteen days with a progressively worsening COPD, a form of emphysema brought on by decades of smoking.

Within a few hours I got on a plane, and spent most of the flight thinking about the past. I prayed that God would give me peace and the wisdom to know what to say when I saw the father who had left us penniless when I was fourteen. By the time I arrived at the hospital, so late at night that I had to enter through the emergency room, a quiet peace pervaded every decision. Within moments I was at his side, shocked at his wizened appearance despite the nurse’s warnings over the telephone that he would look far older than his actual age of seventy-one. Shrunken and gaunt, this 117-pound man with the breathing tube didn’t seem like he could be the larger-than-life specter I remembered from my childhood. He looked piteous, and it was not difficult to find sympathy crowding out every other emotion. Only his famous beak-like nose had retained its full glory.

Here is what I learned from my father’s sudden reappearance and death a few days later: all of my unsuccessful spiritual practices, those attempts at sainthood that felt like dismal failures at the time, actually took hold somehow. They helped to form me into the kind of person who could go to the bedside of someone who had harmed me and be able to say, “I forgive you, Dad. Go in peace.” Although I didn’t see it while I was doing the practices themselves, the power of spiritual practice is that it forges you stealthily, as you entertain angels unawares.

The life of the spirit is one lived for others. My dad, on the other hand, lived opposed to this principle: he was a grasper, always reaching beyond his present circumstances to chase a dream of easy wealth (we found every conceivable get-rich-quick scheme in his files) or restored youth. He did not invest in eternity. I’m sure that God has forgiven my dad, and I can write with honesty that I have forgiven him too. But I don’t want my world to be like his. One way to live the life of the spirit, and offer it to God and others, is through spiritual practices—my daily commitment to implementing a different kind of life.

I know I will implement that spiritual intention far from perfectly. In a culture that stresses perfection, I’ve often heard the maxim that “good is the enemy of perfect”; in other words, when people of faith aim for anything short of godliness we miss the mark. I’ve learned the reverse is true: Perfect is the enemy of good. I may have spent a year flunking sainthood, but along the way I’ve had unexpected epiphanies and wild glimpses of the holy I would never have experienced without these crazy practices. A failed saint is still a saint. I claim that S-word for myself, even with all my letdowns. I turn to Dorothy Day here, who said that we are all called to be saints, “and we might as well get over our bourgeois fear of the name. We might also get used to recognizing the fact that there is some of the saint in all of us. Inasmuch as we are growing, putting off the old [self] and putting on Christ, there is some of the saint, the holy, the divine right there.”

Though Jana Riess is a spiritual failure and was never able to climb the rope in gym class, she has a doctorate from Columbia University and is the author of several books including The Twible and Flunking Sainthood: A Year of Breaking the Sabbath, Forgetting to Pray, and Still Loving My Neighbor, which was named by Publishers Weekly as one of the best religion books of the year. Jana blogs at RNS (http://janariess.religionnews.com/).

Though Jana Riess is a spiritual failure and was never able to climb the rope in gym class, she has a doctorate from Columbia University and is the author of several books including The Twible and Flunking Sainthood: A Year of Breaking the Sabbath, Forgetting to Pray, and Still Loving My Neighbor, which was named by Publishers Weekly as one of the best religion books of the year. Jana blogs at RNS (http://janariess.religionnews.com/).

More about Post-Traumatic Church Syndrome, a humorous, inspirational memoir about Reba’s transformational journey through 30 religions before her 30th birthday

Connect with Reba Riley on Facebook Twitter Reba Riley.com

Read FOUR FREE CHAPTERS of Post-Traumatic Church Syndrome